[Image from Shawn Rocco/Duke Health]

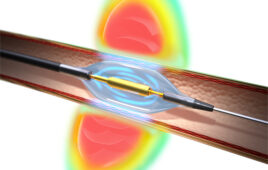

A team of doctors and engineers at Duke University and Stanford University have used a fingernail-sized microchip that is mounted on a traditional ultrasound probe to relay 2D images of what is under the skin. The chip uses the probe’s location and software to put together hundreds of individual slices of the anatomy of the part of the body it goes over to create 3D images.

The resulting images are similar to what a CT scan or MRI produces. It allows for 2D ultrasound machines with higher resolution to have clearer 3D pictures.

“With 2D technology you see a visual slice of an organ, but without any context, you can make mistakes,” Joshua Broder, an emergency physician and associate professor of surgery at Duke University, said in a press release. “These are problems that can be solved with the added orientation and holistic context of 3D technology. Gaining that ability at an incredibly low cost by taking existing machines and upgrading them seemed like the best solution to us.”

Broder thought of the idea to use an accelerometer while playing the Nintendo Wii in 2014. He noticed that the console could accurately track the position of the controller and thought he could duct tape a controller to an ultrasound probe.

He took his idea to a team of engineers at Duke University who used a 3D printer to create a prototype. They started with a streamlined plastic holster that is able to be slipped onto the ultrasound probe. The probe can be used as it normally can be used. Technicians can also add 3D images by snapping a plastic attachment that has a location-sensing microchip onto the probe. The team also created a plastic stand that steadies the probe as the technician focuses on one part of anatomy to get the best 3D images.

The ultrasound probe and the microchip are connected to a laptop that is programmed for the device through computer cables. As a technician scans using the probe, the computer program creates a 3D model in a few seconds.

“Ultrasound is such a beautiful technology because it’s inexpensive, it’s portable, and it’s completely safe in every patient,” said Broder. “And it’s brought to the bedside and it doesn’t interfere with patient care.”

Duke and Stanford researchers are testing the technology in clinical trial to see how it works in patient care. They hope it can be used in occasions when CT scans or MRIs are unavailable, in rural or developing areas or when the scans are too risky.

“With trauma patients in the emergency department, we face a dilemma,” Broder said. “Do we take them to the operating room not knowing the extent of their internal injuries or bleeding, or do we risk transporting them to a CT scanner, where their condition could worsen due to a delay in care? With our new 3-D technique, we hope to demonstrate that we can determine the source of bleeding, measure the rate of bleeding right at the bedside and determine whether an operation is really needed.”

The team is also working on filling the gaps between their 3D ultrasound systems and 3D machines already on the market.

“In emergency medicine, we use ultrasound to look at every part of the body — to look at blood vessels that we put catheters into, to checking on a trauma patient to see where they’re bleeding,” Broder said. “In this case we can augment 2-D machines and improve every one of those applications. Instead of looking through a keyhole to understand what’s in the room, we can open a door and see everything in front of us.”

The research was supported by Stanford’s branch of the Wallace H. Coulter Foundation.