You know how the story goes—especially if you were an accident-prone child like I was—you get a cut, race back inside to get a (hopefully not painful) antiseptic and a bandage. But despite your best preventative efforts, some especially gung-ho bacteria infects the wound anyway. Unfortunately, bacterial infection is a common and possibly dangerous complication of wound healing.

But what if the bandage you wore to protect from infection did more than simply put up a wall against invaders? What if it could somehow warn you that the bacterial onslaught has begun?

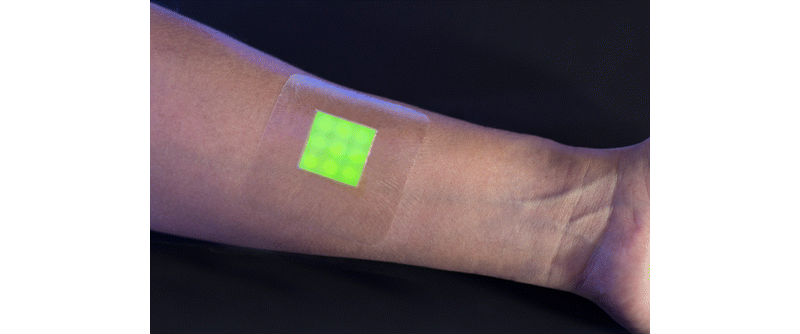

Thanks to research from the University of Bath, we may very well have a bandage that glows green at the onset of infection. The prototype color-changing bandage contains a material similar to a gel that is imbued with small capsules, which release a fluorescent dye when it comes in contact with the types of bacteria that can cause wound infections. Hopefully, it will be able to signal doctors that an infection is imminent with enough time to prevent the patient from getting sicker—even perhaps avoid the use of antibiotics entirely.

The immune system is usually able to get rid of small populations of pathogenic bacteria. Sometimes the amount of harmful bacteria overwhelms the immune system, necessitating clinical intervention. The researchers believe that process happens over several hours before symptoms become noticeable. The earlier the detection, the longer doctors have to attack the infection before it becomes more serious.

The researchers also believe the transition occurs due to a biofilm (layer of microbes) secreting a substance that defends the colony against the immune system. Once the bacterial population becomes too high, they then begin to secrete toxins.

The dressings works because the outer layer of the bandage’s capsules mimics the cell membrane. Toxins enter the capsules much like they would cells, releasing the dye, which then fluoresces when covered by the surrounding gel.

There’s no ignoring it when a bandage–rather than a mother–tells you you’re going to get an infection.

It’s thus far unknown as to what the clinical use for the color-changing bandage might be, but the researchers believe a good place to start would be burn victims. Antibiotics are frequently overprescribed to burn wounds—particularly in children, where the researchers have set their sights on collaboration, with the pediatric burn center at the University of Bristol. This can bring about antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria, and the bandage might be able to reassure both patients and doctors that a wound is not yet infected. The bandage might also be useful for monitoring surgical and traumatic injury wounds.

The bandages have been proven to fluoresce after detecting biofilms of three types of pathogenic bacteria. It wasn’t a fluke as far as the researchers could tell, either; the non-pathogenic bacteria did not light up the bandage.

The team continues to develop their bandage thanks to a grant from the UK’s Medical Research Council, to detect infections from wound swabs and blister fluid from pediatric burn victims. It hasn’t yet been tested on humans—the bandage will hopefully undergo clinical testing by 2018.