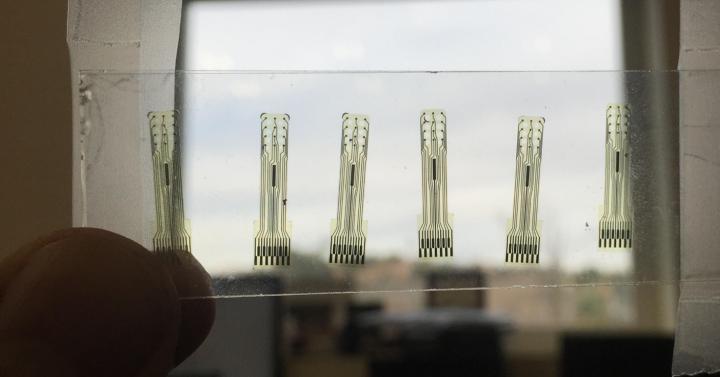

This image shows a sheet of glassy carbon electrodes patterned inside chips. (Credit: Sam Kassegne)

When people suffer spinal cord injuries and lose mobility in their limbs, it’s a neural signal processing problem. The brain can still send clear electrical impulses and the limbs can still receive them, but the signal gets lost in the damaged spinal cord.

The Center for Sensorimotor Neural Engineering (CSNE)–a collaboration of San Diego State University with the University of Washington and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology–is working on an implantable brain chip that can record neural electrical signals and transmit them to receivers in the limb, bypassing the damage and restoring movement.

Recently, these researchers described in a study published in the journal Nature Scientific Reports a critical improvement to the technology that could make it more durable, last longer in the body and transmit clearer, stronger signals.

The technology, known as a brain-computer interface, records and transmits signals through electrodes, which are tiny pieces of material that read signals from brain chemicals known as neurotransmitters. By recording brain signals at the moment a person intends to make some movement, the interface learns the relevant electrical signal pattern and can transmit that pattern to the limb’s nerves, or even to a prosthetic limb, restoring mobility and motor function.

The current state-of-the-art material for electrodes in these devices is thin-film platinum. The problem is that these electrodes can fracture and fall apart over time, said one of the study’s lead investigators, Sam Kassegne, deputy director for the CSNE at SDSU and a professor in the mechanical engineering department.

Kassegne and colleagues developed electrodes made out of glassy carbon, a form of carbon.

This material is about 10 times smoother than granular thin-film platinum, meaning it corrodes less easily under electrical stimulation and lasts much longer than platinum or other metal electrodes.

“Glassy carbon is much more promising for reading signals directly from neurotransmitters,” Kassegne says. “You get about twice as much signal-to-noise. It’s a much clearer signal and easier to interpret.”

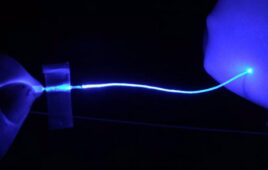

The glassy carbon electrodes are fabricated here on campus. The process involves patterning a liquid polymer into the correct shape, then heating it to 1000 degrees Celsius, causing it become glassy and electrically conductive. Once the electrodes are cooked and cooled, they are incorporated into chips that read and transmit signals from the brain and to the nerves.

Researchers in Kassegne’s lab are using these new and improved brain-computer interfaces to record neural signals both along the brain’s cortical surface and from inside the brain at the same time.

“If you record from deeper in the brain, you can record from single neurons,” explains Elisa Castagnola, one of the researchers. “On the surface, you can record from clusters. This combination gives you a better understanding of the complex nature of brain signaling.”

A doctoral graduate student in Kassegne’s lab, Mieko Hirabayashi, is exploring a slightly different application of this technology. She’s working with rats to find out whether precisely calibrated electrical stimulation can cause new neural growth within the spinal cord. The hope is that this stimulation could encourage new neural cells to grow and replace damaged spinal cord tissue in humans.

The new glassy carbon electrodes will allow her to stimulate, read the electrical signals of and detect the presence of neurotransmitters in the spinal cord better than ever before.