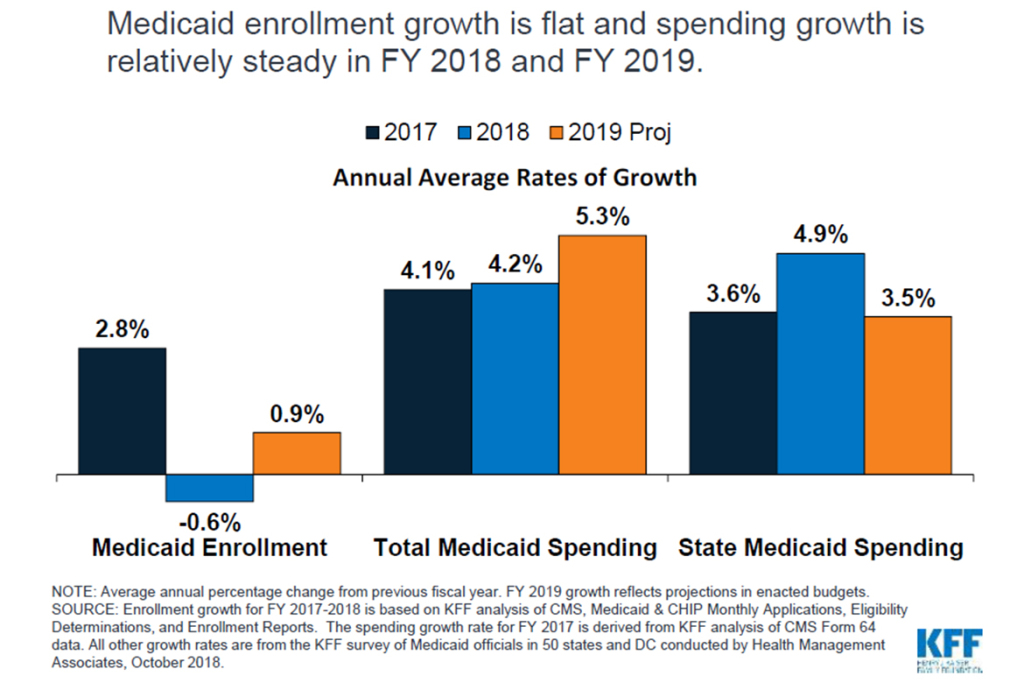

Medicaid enrollment fell by 0.6 percent in 2018 — its first drop since 2007 — due to the strong economy and increased efforts in some states to verify eligibility, a new report finds.

But costs continue to go up. Total Medicaid spending rose 4.2 percent in 2018, same as a year ago, as a result of rising costs for drugs, long-term care and mental health services, according to the study released Thursday by the Kaiser Family Foundation. (Kaiser Health News is an editorially independent program of the foundation.)

States expect total Medicaid spending growth to accelerate modestly to 5.3 percent in 2019 as enrollment increases by about 1 percent, according to the annual survey of state Medicaid directors.

(Image credit: Kaiser Family Foundation)

About 73 million people were enrolled in Medicaid in August, according to a federal report released Wednesday.

Medicaid, the state-federal health insurance program for low-income Americans, has seen its rolls soar in the past decade — initially as a result of massive job losses during the Great Recession and in recent years when dozens of states expanded eligibility using federal financing provided by the Affordable Care Act. Thirty-three states expanded their programs to cover people with incomes under 138 percent of the federal poverty level, or an income of about $16,750 for an individual in 2018.

Medicaid spending and enrollment typically rise during economic downturns as more people lose jobs and health benefits. When the economy is humming, Medicaid enrollment flattens as more people get back to work and can get coverage at work or can afford to buy it on their own. The national unemployment rate was 3.7 percent in September, the lowest since 1969.

The falling unemployment rate is the main reason for the drop in Medicaid enrollment, but some states have reduced their rolls by requiring adults and families to verify their eligibility. Arkansas, for example, has cut thousands of people after instituting new steps to confirm eligibility.

The brightening economic outlook for states has led many to increase benefits to enrollees and payment rates for health providers.

“A total of 19 states expanded or enhanced covered benefits in fiscal 2018 and 24 states plan to add or enhance benefits for the current fiscal year, which for most states started in July,” the Kaiser report said. “The most common benefit enhancements reported were for mental health and substance abuse services. A handful of states reported expansions related to dental services, telehealth, physical or occupational therapies and home visiting services for pregnant women.”

A dozen states increased pay to dentists and 18 states added to primary care doctors’ reimbursements for fiscal year 2019.

(Image credit: Associated Press)

Medicaid covers about 20 percent of U.S. residents and accounts for nearly one-sixth of health care expenditures. Nearly half of enrollees are children.

Overall, the federal government pays about 62 percent of Medicaid costs with state’s picking up the rest. Poorer states get a higher federal match rate.

Seventeen Republican-controlled states have not expanded Medicaid. For individuals accepted into the program as part of the ACA expansion, the federal government paid the full cost of coverage from 2014 through 2016. It will pay no less than 90 percent thereafter.

In 2018, the states’ share of spending rose 4.9 percent. This was the first full year that states were responsible for part of the cost of the expansion. States expect their spending will grow about 3.5 percent in 2019.

Robin Rudowitz, one of the authors of the study and associate director of the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, said the survey found many states were using Medicaid to address the opioid crisis by expanding benefits for substance disorders and also by implementing tougher restrictions on prescriptions.

“Almost every governor wants to do something, and Medicaid is generally a large part of it,” she said.

While the Trump administration’s approval of work requirements for some adults on Medicaid has generated controversy over the past year, the report shows that states are making many other changes to the program, such as increasing benefits and changing how it pays providers to get better value.