[Image from MIT]

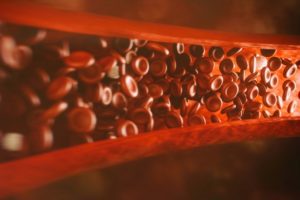

The MIT researchers developed a compound that reactivates longevity-linked proteins also promotes the growth of blood vessels and muscle to help boost the endurance of elderly mice in the study. The growth of blood vessels boosted the endurance of mice by up to 80%.

The big question is whether similar results can be achieved in humans. Restoration of muscle mass in humans could help alleviate the effects of age-related frailty, preventing osteoporosis and other similar conditions, according to the researchers

“We’ll have to see if this plays out in people, but you may actually be able to rescue muscle mass in an aging population by this kind of intervention,” Leonard Guarente, one of the study’s senior authors at MIT, said in a press release. “There’s a lot of crosstalk between muscle and bone, so losing muscle mass ultimately can lead to loss of bone, osteoporosis and frailty, which is a major problem in aging.”

Guarente discovered in the early 1990s that sirtuins, a class of proteins that are found in animals, could protect against the effects of aging in yeast. Following the discovery, the proteins have had similar effects in other organisms.

The researchers wanted to test the role of sirtuins in endothelial cells that line blood vessels. They deleted the gene that encodes major mammalian sirtuin, SIRT1, in endothelial cells in mice. At six months old, the mice had reduced capillary density and could only run half as far as a normal six month old mouse.

Guarente and his colleagues boosted sirtuin levels in normal mice as they aged while treating them with a NMN compound that is a precursor to NAD, a coenzyme that activates SIRT1. Normally, NAD levels drop as an animal ages. The researchers suggest that it is caused by a reduced NAD production and faster NAD degradation.

Mice that were 18 months old were treated with NMN for two months. Their capillary density was restored to levels that are normally seen in younger mice. They also experienced a 56% to 80% endurance improvement. The effects were also seen in mice up to 32 months old, which is equivalent to humans in their 80s.

“In normal aging, the number of blood vessels goes down, so you lose the capacity to deliver nutrients and oxygen to tissues like muscle, and that contributes to decline,” Guarente said. “The effect of the precursors that boost NAD is to counteract the decline that occurs with normal aging, to reactivate SIRT1, and to restore function in endothelial cells to give rise to more blood vessels.”

They also found that SIRT1 activity in endothelial cells is important for the effects of exercise which can stimulate the growth of new blood vessels while boosting muscle mass. But when the researchers stoped SIRT1 in endothelial cells of 10-month old mice and put them on a four-week treadmill running program, exercise didn’t create the same gains that were seen in normal 10 month old mice on the same training program.

The researchers suggest that if the sirtuin levels were boosted in humans, it may help older people retain muscle mass using exercise.

“What this paper would suggest is that you may actually be able to rescue muscle mass in an aging population by this kind of intervention with an NAD precursor,” Guarente said.

The research was published in the journal Cell and was funded by the Glenn Foundation for Medical Research, the Sinclair Gift Fund, a gift from Edward Schulak and the National Institutes of Health.