Cleveland Clinic lead investigator Paul Marasco (left) and visiting researcher Zachary Thumser (right) with the bionic arm they created. [Image courtesy of Cleveland Clinic]

Upper-limb amputees often have to constantly watch their prosthetics while using them to make corrections in how much grasping force they use, but Cleveland Clinic said patients testing the new bionic arm system used it with less effort and an easier learning curve.

“Perhaps what we were most excited to learn was that they made judgments, decisions and calculated and corrected for their mistakes like a person without an amputation,” lead investigator Paul Marasco said in a news release. “With the new bionic limb, people behaved like they had a natural hand. Normally, these brain behaviors are very different between people with and without upper limb prosthetics.”

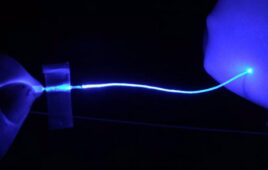

The bionic system combines a neural-machine interface with three crucial functions: intuitive motor control, touch and grip kinesthesia, which is the intuitive feeling of opening and closing your hand. The two-way neural-machine interface lets patients control the prosthetic with nerve impulses from their brains to the prosthetic, which sends feedback along the nerves back to the brain.

“We modified a standard-of-care prosthetic with this complex bionic system, which enables wearers to move their prosthetic arm more intuitively and feel sensations of touch and movement at the same time,” said Marasco, the neuroscientist and associate professor who leads the Laboratory for Bionic Integration in the Lerner Research Institute’s Department of Biomedical Engineering.

[Image courtesy of Cleveland Clinic]

Two patients tested the bionic arm after undergoing targeted sensory and motor reinnervation procedures to connect their limb nerves with the neural-machine interface. In targeted sensory reinnervation, small robots touch the skin to activate sensory receptors so patients can feel the sensation of touch. In targeted motor reinnervation, reinnervated muscles communicate limb-moving thoughts to control the computerized prosthesis, while small robots vibrate kinesthetic sensory receptors in those muscles to send feelings of hand and arm movement.

More research and testing are needed due to the small study group, but Marasco said the technology could in the future “offer prosthesis wearers new levels of seamless reintegration back into daily life.”

And it’s possible to apply the research team’s brain behavior and functionality insights to other upper limb prosthetics or deficits in sensation and movement, according to the researchers.

Cleveland Clinic led the international research team, which included collaboration from the University of Alberta and the University of New Brunswick. The study was partially funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) in the U.S. Department of Defense.