Recent advances in battery technology, from the engineering of their cases to the electrochemistry that takes place inside them, has enabled the rapid rise of Teslas, Leafs, Volts and other electric cars.

Now, scientists at Scripps Research, inspired by the refined electrochemistry of these batteries, have developed a battery-like system that allows them to make potential advancements for the manufacturing of medicines.

Their new method, reported today in Science, avoids safety risks associated with a type of chemical reaction known as dissolving metal reduction, which is often used to produce compounds used in the manufacturing of medicines. Their method would offer tremendous advantages over current methods of chemical manufacturing, but until now, has largely been sidelined due to safety considerations.

“The same types of batteries we use in our electric cars today were far too dangerous for commercial use a few decades ago, but now they are remarkably safe thanks to advances in chemistry and engineering,” says Phil Baran, Ph.D., who holds the Darlene Shiley Chair in Chemistry at Scripps Research and is a senior author of the Science paper. “By applying some of the same principles that made this new generation of batteries possible, we have developed a method to safely conduct powerfully reductive chemical reactions that have very rarely been used on a large scale because—until now—they were too dangerous or costly.”

“This could have a major impact on not only the manufacturing of pharmaceuticals,” Baran adds, “but also on the mindset of medicinal chemists who traditionally avoid such chemistry due to safety concerns. This problem was in fact brought to our attention by co-author Michael Collins, a medicinal chemist at Pfizer, for precisely this reason.”

One of the most powerful reactions, and representative examples of this deeply reducing chemistry that chemists use to make new molecules is the Birch reduction, which was largely pioneered by Australian chemist Arthur Birch in the 1940s. This reductive reaction involves dissolving a reactive metal in liquid ammonia to manipulate ring-shaped molecules that can be used as the foundation for making many chemical products, including drug molecules.

The procedure calls for condensing ammonia or similar compounds, which are corrosive, toxic and volatile, and combining it with metals such as lithium that are prone to bursting into flames if exposed to air. The process must take place at extremely cold temperatures, requiring expensive equipment, and specialists.

A rare example of the use of a dissolving metal reduction in pharmaceutical manufacturing is a Parkinson’s disease drug candidate (sumanirole) developed by Pfizer, a remarkable achievement in chemical manufacturing that required a herculean effort. The system to produce the compound on a large scale requires enough gaseous ammonia to fill three Boeing 747 airliners and must be conducted at -35 degrees Celsius. The lengths to which Pfizer went to utilize this chemistry are a testimony to the reaction’s its synthetic power, and the great desire to use it in large-scale manufacturing over any known method.

To overcome these significant barriers to using such chemistry, Baran and his team looked to the advances made in battery manufacturing by joining forces with experts at the University of Utah, led by Shelley Minteer, Ph.D., and the University of Minnesota, led by Matthew Neurock, Ph.D.

The lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries used in modern electronics such as mobile phones, laptop computers and electric cars rely on advances in an internal component called the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI). The SEI is a protective layer that forms on one of the electrodes inside a Li-ion when the battery is first charged and allows the battery to be recharged. Producing the safe and efficient batteries now used in consumer electronics relied on years of advances in optimizing the chemical conditions—the composition of electrolytes, solvents and additives—that produced the SEI.

The team noted that the reaction that forms the SEI in batteries is an electrochemical reaction akin to the Birch reaction and its relatives. They surmised that they could borrow from what battery makers had learned to pursue a safe and practical method of conducting electroreduction reaction.

“In many ways you’re looking at similar situations—powerful reactions that, when effectively harnessed, can provide tremendous utility,” says Solomon Reisberg, a graduate student in the Baran lab and one of the co-authors on the Science paper. “The team took advantage of the hard-won knowledge about the conditions that make reductive electrochemistry in batteries practical and used that knowledge to rethink how deeply reductive chemistry could be used on a large scale.”

The Scripps Research team began by testing a range of additives used to prevent overcharging in Li-ion batteries and found that a combination of two them, substances called dimethylurea, and TPPA, made the Birch reaction possible at room temperature.

Testing various other materials used in batteries, Baran’s team came up with a set of conditions that allowed them to not only conduct reductive electrosynthesis safely but also to increase the versatility of the reaction to create a wider variation of products that was not possible with previous electrochemical methods.

This method avoided the need for dissolving liquid metals in large quantities of ammonia—and the associated cost and risks—and instead used an electrolyte system similar to that used in batteries. In addition to the Birch reaction, the researchers were able to apply the technique to other types of powerful reactions often used in synthesis but rarely, if ever, used in an industrial settings.

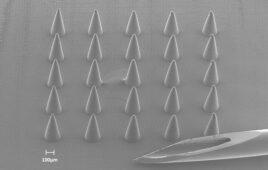

The researchers synthesized multiple versions of important single-ring compounds as well as molecules where multiple rings were combined to create more complex structures—structures that form the skeletons of drugs and other chemical products. In contrast to the enormously expensive devices previously required to conduct reductive chemistry in large quantities, the team collaborated with Asymchem Life Science, a chemical manufacturer based in Tianjin, China, to build a small modular device capable of generating large quantities of products for less than $250.

“This demonstrates that kilogram-scale synthesis of pharmaceutically relevant building blocks can be produced by adapting what we’ve learned about electrochemistry from the rapid advance of battery technology,” Baran says. “We anticipate that this will be a boon to industry, allowing them to finally bring these reactions to practical use.”

Scientists at Scripps Research, inspired by the refined electrochemistry of these batteries, have developed a battery-like system that allows them to make potential advancements for the manufacturing of medicines. Their system avoids safety risks associated with a type of chemical reaction known as dissolving metal reduction, which is often used to produce compounds used in the manufacturing of medicines. Credit: Baran lab