The future of implanted medical devices: is it fully implantable, closed-looped computerized systems that replace failed organs, or is it completely externalized technologies with enough power and intelligence to be therapeutic across the human body’s defenses that protect it from the outside world? The customers have spoken: “Is it too much to ask for both?”

Many clinicians across various specialties have previously said that “the best implant is no implant.” This statement is not without merit due to the history of implant related failure modes including infection, skin erosion, the need for surgical battery replacement, post-op “pocket pain,” etc. The challenge has brought about technologies such as bioabsorbable stents and craniofacial/orthopedic fixation devices, but what about active implants that are tasked with being therapeutic over a lifetime?

No specialty has been tested by this task more than neuromodulation. The International Neuromodulation Society defines therapeutic neuromodulation as “the alteration of nerve activity through targeted delivery of a stimulus, such as electrical stimulation or chemical agents, to specific neurological sites in the body.” The world is only very recently seeing the true potential of what neuromodulation can accomplish with Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, chronic pain from a variety of etiologies, etc.

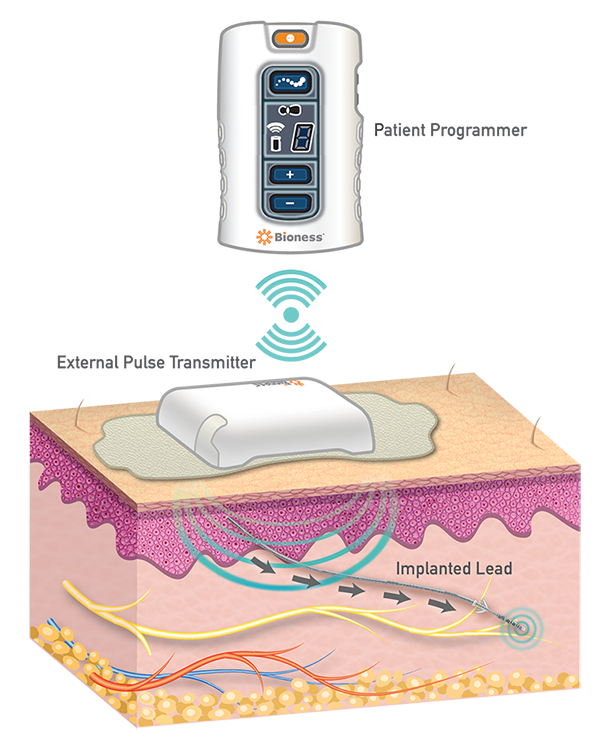

In order to be successful, implantable neuromodulation devices need to be separated into individual components. Fortunately, implantable neurostimulators can be broken down into logical pieces allowing medical device designers to simplify implant technology, which can reduce surgery time, patient recovery time, and complications. This can also allow for the combination of technologies from multiple clinical applications. Neuromodulation does just that by combining technology from neurosurgery and cardiology, with a little splash of Cable TV to put the patient in a familiar driver’s seat- in control of their electronic environment. Pictured below in Figure 1 is an example of how technology from multiple specialties can work.

Figure 1. StimRouter Neuromodulation System (Credit: Mark Geiger)

When the implanted portion of the system is passive it reduces the complexity of the implant, improving the ease of explant when/if required, and reducing the need for additional surgeries to repair or replace parts. Patients with these types of implants often ask when they would have to take the implant out. However, the concept of life-long implants, both passive and active, is one that is here to stay and will bring great benefits to future patients. Many people don’t want the type of “wearable” fictional characters like Darth Vader don, but what about Iron Man? Could a tiny implant, combined with a wearable, make you a “better human”? Early versions of this are already being used by patients with cochlear and retinal implants, drug pumps, neurostimulators, and functional electrical stimulation devices. But, I digress.

The neuromodulation device pictured above has three distinct components: the implanted “Lead,” the External Pulse Transmitter, and the Patient Programmer. The clinician loads different stimulation programs onto the patient programmer and prescribes how the patient uses it and how often. The external pulse transmitter delivers a specific electric field through the skin that is picked up by the receiver, built into the implanted lead, and then transmits that energy to the electrodes on the lead’s tip to stimulate the target peripheral nerve and significantly reduce chronic pain. Different stimulation parameters (amplitude, pulse width, frequency) can be adjusted by the clinician to meet the patient’s needs.

Design change proposals enhancing capability or reducing cost of any of the three components, especially the wearable, can be executed without necessarily forcing changes to the other components. Battery size & type, RAM, and CPU changes even ten years ago would require overhauling the entire system in the fully implantable pulse generators of the past. This is not the case with the newer medical devices of today. In 1972 when Michael Crichton wrote The Terminal Man, art and science fiction was just that, fiction. Now, over 40 years later, it’s life that is imitating art and it makes you wonder if someone has already solved the issue of size, efficiency, manufacturability, and ease of use in other areas of medicine or aerospace. There’s a good chance someone has.

Mark Geiger’s Bio:

Mark Geiger is the Global Director of Marketing for Implantables at Bioness Inc. (Valencia, CA) and has spent over 25 years in the Medical Device Business.