Replacing and repairing human tissue is becoming feasible largely due to advances in the use of stem cells. Unfortunately, obstacles still stand in the way of engineering these malleable cells to self-renew or expand.

One of those obstacles is an incomplete picture of how cells interact with their environment.

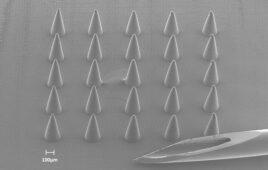

“Cells do not simply reside within a material, they actively reengineer it,” said Kelly Schultz, P.C. Rossin assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at Lehigh University’s P.C. Rossin College of Engineering and Applied Science. “Characterizing how cells behave in Three-Dimensional (3-D) synthetic material is critical to advancing biomaterial design used in wound healing, tissue engineering and stem cell expansion.”

Schultz recently received a three-year grant from National Institutes of Health grant (NIH) (Award date: May 9, 2016) to study how cells remodel their microenvironment—a crucial step toward engineering cells to move through synthetic material and tissue more quickly for faster wound healing and tissue regeneration.

Schultz will build on previous work in which she and her colleagues revealed that during attachment, spreading and motility, cells degrade material in the pericellular region–the region directly around the cell—in an entirely different manner than researchers had previously believed. The results were published in an article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Prior to Schultz’s earlier study, scientists believed cells moved through material while simultaneously degrading it, like a Pac Man gobbling up dots while making its way through a video game maze.

Utilizing microrheology, a technique that measures the properties and states of matter, Schultz and her colleagues made a discovery that overturned this notion. After encapsulating mesenchymal stem cells in a hydrogel, the team measured dynamic interactions between the cells as they moved through material.

They made an unexpected observation: the cells pause before moving. They discovered that from a stationary position, Point A, a given cell secretes an enzyme. They hypothesize that the enzyme is bound together with an inhibitor that temporarily stops the enzyme from degrading the material while it’s being sent to Point B. Starting at Point B, the enzyme begins to “gobble up” the material that surrounds the cell. Only then does the cell move on to its next location.

The inhibitor, they observed, prevents the enzyme from degrading the material while the cell is secreting it.

Armed with this information, Schultz and her team now aim to “inhibit the inhibitor.” That is, they seek to identify which inhibitor, or combination of inhibitors, is responsible for stopping the enzyme from degrading the material while it’s being secreted. Once identified, the researchers hope to “tune” the inhibitor to shut off during secretion so that the cell will move through and degrade the material faster.

Engineering the cell to move faster is important for wound healing, Schultz said, since the sooner the cells arrive at the wound site, the sooner they can start to regenerate the tissue.

“Our goal is to prevent the cell from stalling, encouraging it to become active right away and arrive at the wound site at twice the speed,” Schultz said.