Altering human heredity? In a first, researchers safely repaired a disease-causing gene in human embryos, targeting a heart defect best known for killing young athletes — a big step toward one day preventing a list of inherited diseases.

In a surprising discovery, a research team led by Oregon Health and & Science University reported Wednesday that embryos can help fix themselves if scientists jump-start the process early enough.

It’s laboratory research only, nowhere near ready to be tried in a pregnancy. But it suggests that scientists might alter DNA in a way that protects not just one baby from a disease that runs in the family, but his or her offspring as well. And that raises ethical questions.

“I for one believe, and this paper supports the view, that ultimately gene editing of human embryos can be made safe. Then the question truly becomes, if we can do it, should we do it?” says Dr. George Daley, a stem cell scientist and dean of Harvard Medical School. He wasn’t involved in the new research and praised it as “quite remarkable.”

“This is definitely a leap forward,” agrees developmental geneticist Robin Lovell-Badge of Britain’s Francis Crick Institute.

In this July 31, 2017 photo provided by Oregon Health & Science University, Shoukhrat Mitalipov, left, talks with research assistant Hayley Darby in the Mitalipov Lab at OHSU in Portland, Ore. Mitalipov led a research team that, for the first time, used gene editing to repair a disease-causing mutation in human embryos, laboratory experiments that might one day help prevent inherited diseases from being passed to future generations. (Kristyna Wentz-Graff/Oregon Health & Science University via AP)

Today, couples seeking to avoid passing on a bad gene sometimes have embryos created in fertility clinics so they can discard those that inherit the disease and attempt pregnancy only with healthy ones, if there are any.

Gene editing in theory could rescue diseased embryos. But so-called “germline” changes — altering sperm, eggs or embryos — are controversial because they would be permanent, passed down to future generations. Critics worry about attempts at “designer babies” instead of just preventing disease, and a few previous attempts at learning to edit embryos, in China, didn’t work well and, more importantly, raised safety concerns.

In a series of laboratory experiments reported in the journal Nature, the Oregon researchers tried a different approach.

They targeted a gene mutation that causes a heart-weakening disease, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, that affects about 1 in 500 people. Inheriting just one copy of the bad gene can cause it.

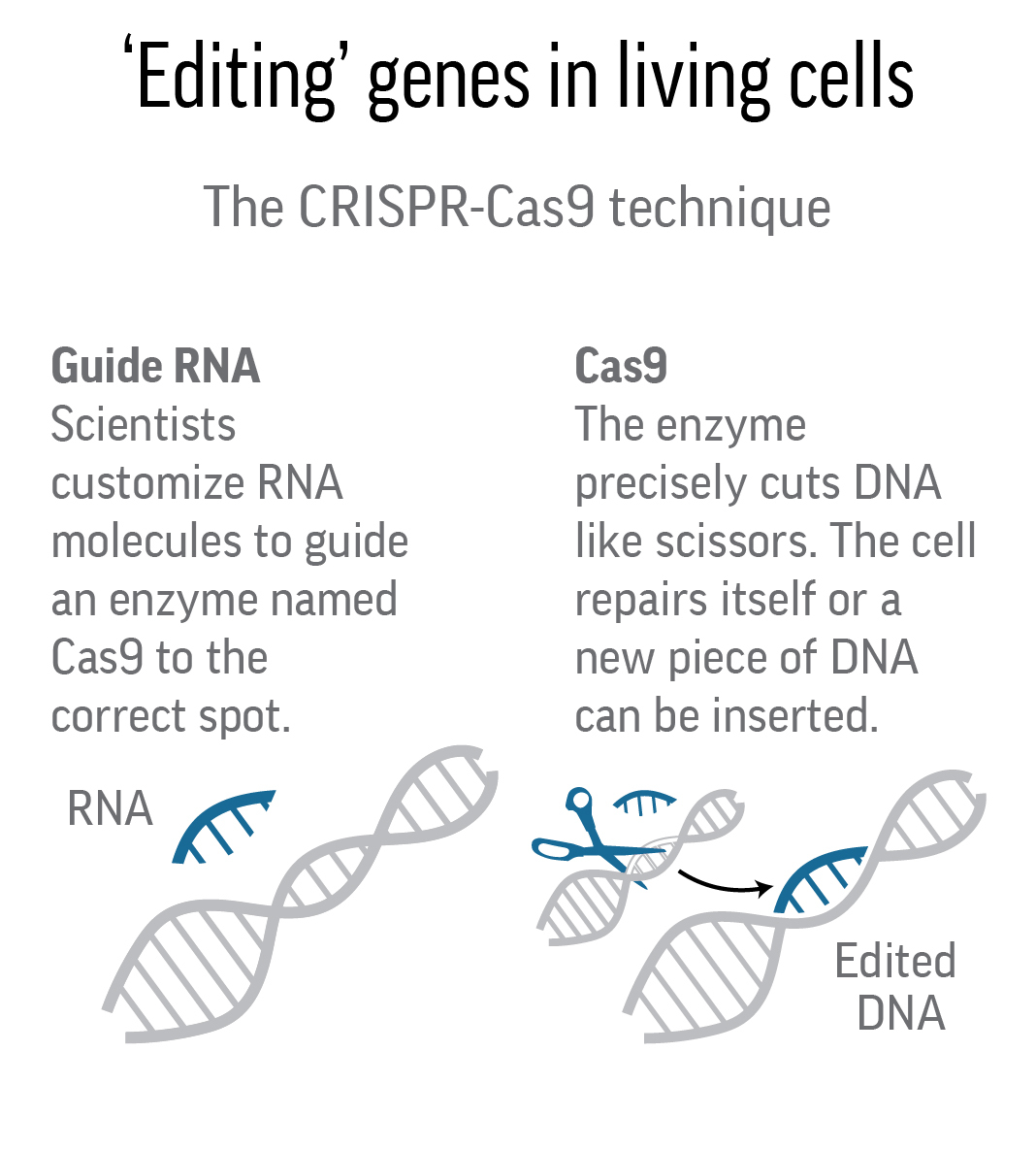

The team programmed a gene-editing tool, named CRISPR-Cas9, that acts like a pair of molecular scissors to find that mutation — a missing piece of genetic material.

Then came the test. Researchers injected sperm from a patient with the heart condition along with those molecular scissors into healthy donated eggs at the same time. The scissors cut the defective DNA in the sperm.

Normally cells will repair a CRISPR-induced cut in DNA by essentially gluing the ends back together. Or scientists can try delivering the missing DNA in a repair package, like a computer’s cut-and-paste program.

Instead, the newly forming embryos made their own perfect fix without that outside help, reported Oregon Health & Science University senior researcher Shoukhrat Mitalipov.

We all inherit two copies of each gene, one from dad and one from mom — and those embryos just copied the healthy one from the donated egg.

“The embryos are really looking for the blueprint,” Mitalipov, who directs OHSU’s Center for Embryonic Cell and Gene Therapy, says. “We’re finding embryos will repair themselves if you have another healthy copy.”

It worked 72 percent of the time, in 42 out of 58 embryos. Normally a sick parent has a 50-50 chance of passing on the mutation.

Previous embryo-editing attempts in China found not every cell was repaired, a safety concern called mosaicism. Beginning the process before fertilization avoided that problem: Until now, “everybody was injecting too late,” Mitalipov says.

Nor did intense testing uncover any “off-target” errors, cuts to DNA in the wrong places, reported the team, which also included researchers from the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in California and South Korea’s Institute for Basic Science. The embryos weren’t allowed to develop beyond eight cells, a standard for laboratory research. The experiments were privately funded; U.S. tax dollars aren’t allowed for embryo research.

Genetics and ethics experts not involved in the work say it’s a critical first step — but just one step — toward eventually testing the process in pregnancy, something currently prohibited by U.S. policy.

“This is very elegant lab work,” but it’s moving so fast that society needs to catch up and debate how far it should go, says Johns Hopkins University bioethicist Jeffrey Kahn.

And lots more research is needed to tell if it’s really safe, added Britain’s Lovell-Badge. He and Kahn were part of a National Academy of Sciences report earlier this year that said if germline editing ever were allowed, it should be only for serious diseases with no good alternatives and done with strict oversight.

“What we do not want is for rogue clinicians to start offering treatments” that are unproven, as has happened with some other experimental technologies, he stresses.

Among key questions: Would the technique work if mom, not dad, harbored the mutation? Is repair even possible if both parents pass on a bad gene?

Mitalipov is “pushing a frontier,” but it’s responsible basic research that’s critical for understanding embryos and disease inheritance, noted University of Pittsburgh professor Kyle Orwig.

In fact, Mitalipov said the research should offer critics some reassurance: If embryos prefer self-repair, it would be extremely hard to add traits for “designer babies” rather than just eliminate disease.

“All we did is un-modify the already mutated gene.”