A pinch of poison is good for a body, at least if it’s heme.

In minuscule amounts, it works in cells as an essential catalyst called a cofactor and as a signaling molecule to trigger other processes. Now, for the first known time, researchers have tracked those activities inside of cells.

“Poor heme management can cause things like Alzheimer’s, heart disease, and some types of cancers, so cells have to do a good job of managing how much heme is available,” said Amit Reddi, a biochemist and assistant professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology. “By having biosensors that can monitor heme in cells, we have this new window into how cells make this essential toxin available in carefully sparse concentrations,” he said.

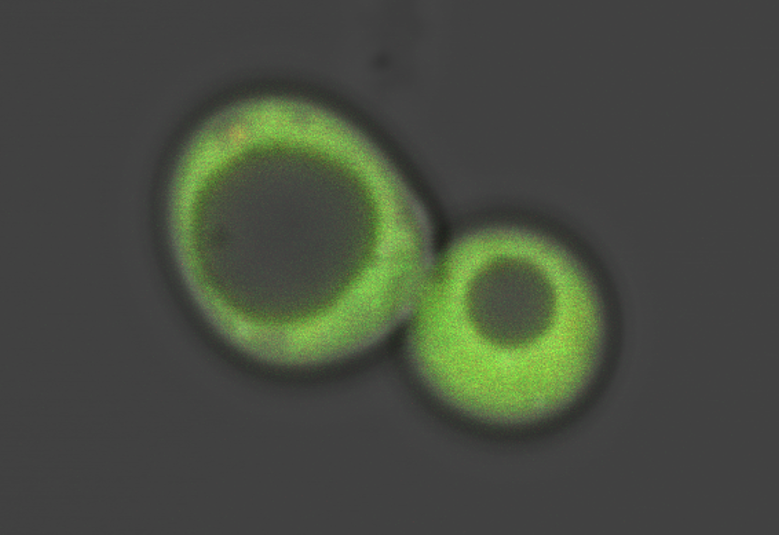

A tailor-made ratiometric sensor makes a baker’s yeast cell light up green, as Georgia Tech scientists use it to track the movements of the essential toxin heme. (Credit: David Hanna/Georgia Tech)

‘Heme’ as in ‘Hemoglobin’

People may recognize heme from its role at the core of hemoglobin, the component of red blood cells responsible for transporting oxygen. The ionic iron in the heme molecule is what the oxygen molecule sticks to.

In hemoglobin, the heme is embedded tightly in protein, rendering it non-toxic. Many scientists have long assumed that heme, even in other cells, is basically always static, held tight by the proteins it works with.

But the researchers’ results shatter that assumption.

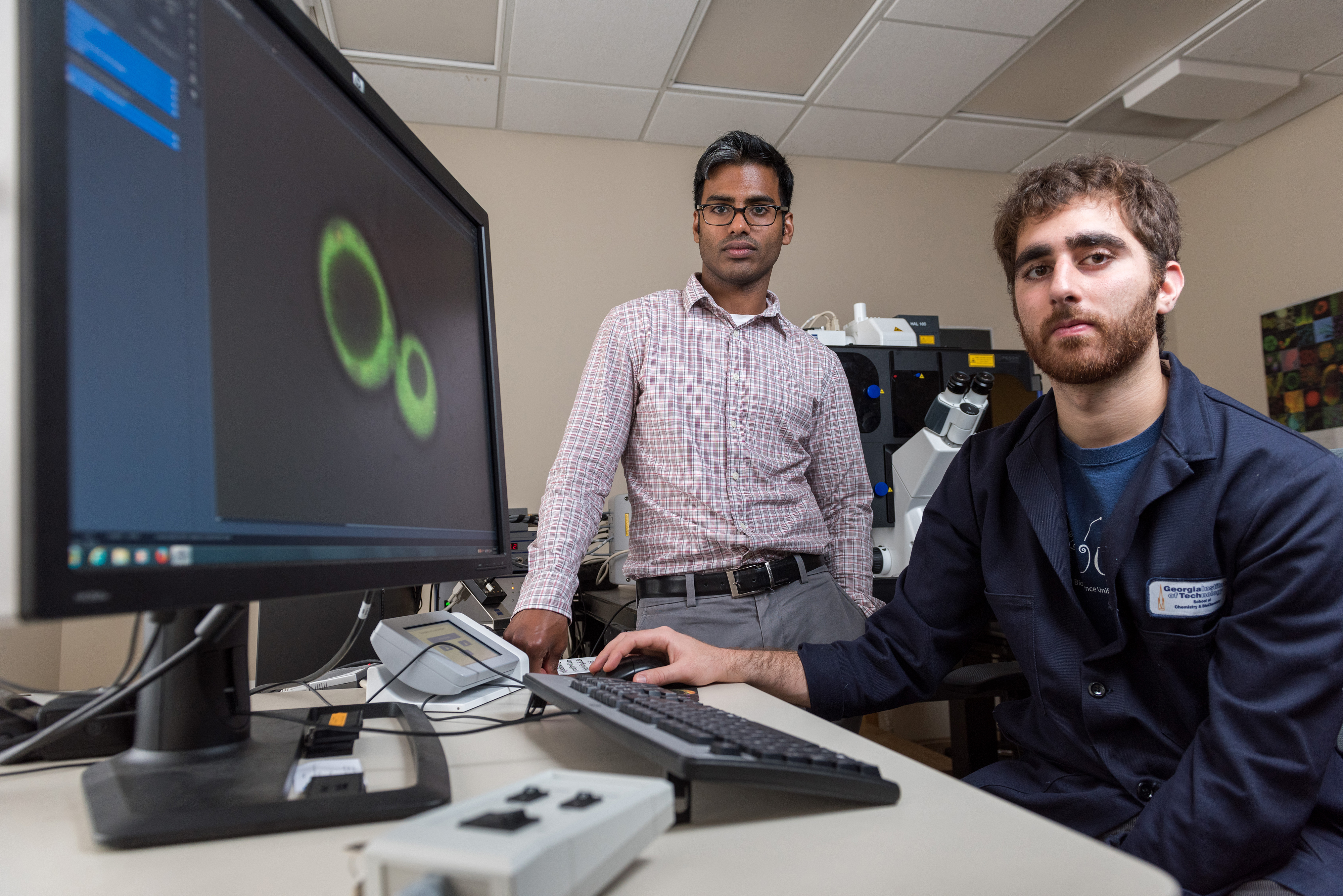

Principal investigator Amit Reddi and lead researcher David Hanna observe an image of a baker’s yeast cell taken under a microscope as it lights up green from the tailor made fluorescent ratiometric sensor they have infused it with. (Credit: Rob Felt/Georgia Tech)

They published their findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, on Monday, May, 30, 2016. Their research is funded by the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health.

Potentially Hazardous Nutrient

The labile heme serves as a nutrient instead of a poison. But to make sure things stay that way, heme needs to be carefully trafficked through the cell, Reddi said.

The research team, led by Reddi and Hanna, designed a fluorescent sensor molecule to keep tabs on that. With heme at very low baseline levels, the sensor lit up bright green then as heme concentration increased, it caused the light to fade out.

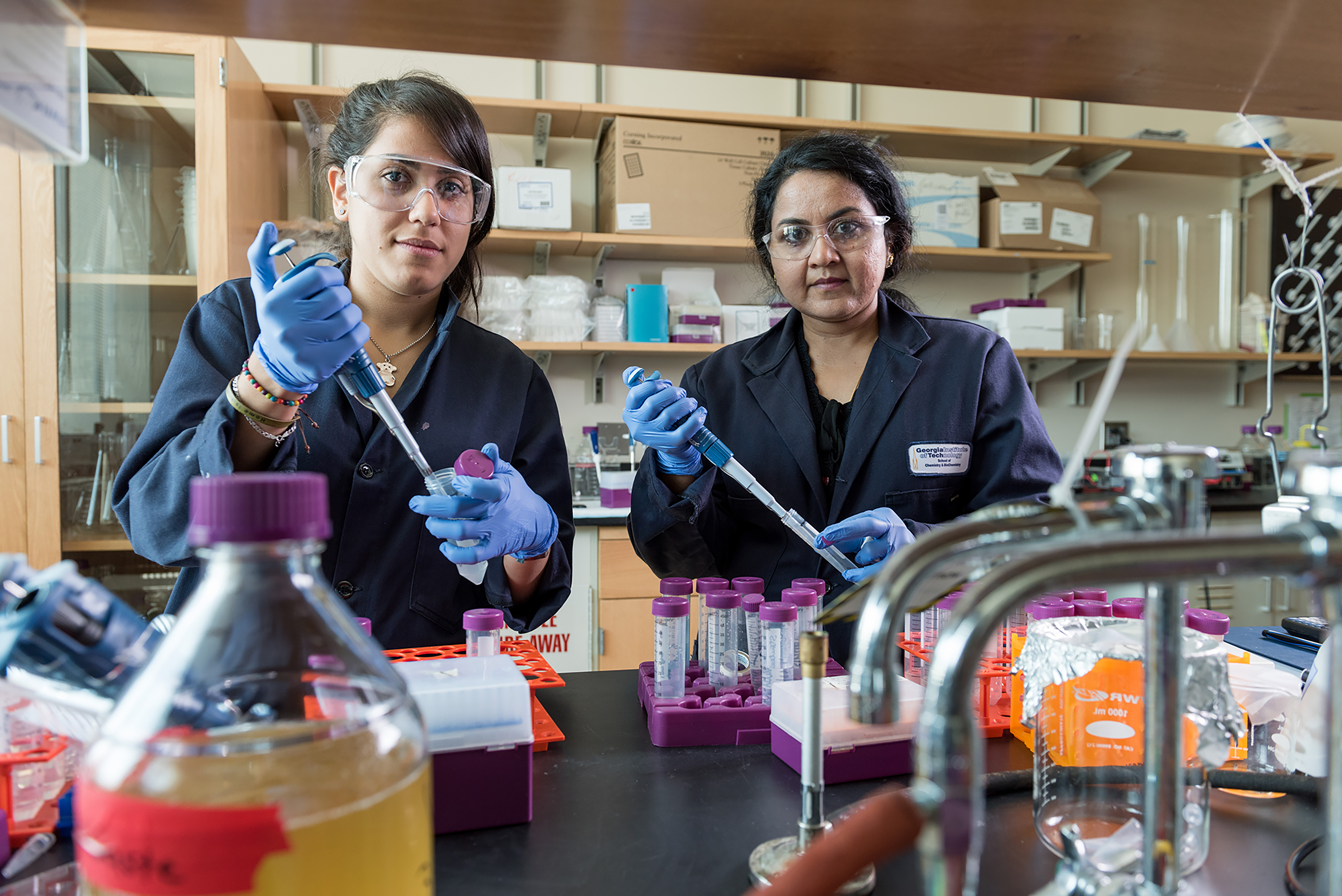

Osiris Martinez-Guzman and Bindu Chandrasekharan coauthored the study that tracked labile heme’s movements in cells for the first known time. (Credit: Rob Felt/Georgia Tech)

Using the heme sensors, Georgia Tech graduate student Osiris Martinez-Guzman found an enzyme, GAPDH, known for its involvement in breaking down sugar, that the team observed helping buffer cellular labile heme (iron protoporphyrin IX), which got tied up in proteins, leaving only a limited amount free for biochemical reactions.

When more labile heme is needed, nitric oxide, a signaling molecule, rapidly released heme from entangling proteins, so it could do jobs such as regulating gene expression.

‘Green Lantern’ Glow

“If you increase nitric oxide, you see the green glowing sensor dim as the heme becomes labile then the glow brightens back up over time as heme gets bound up again,” Reddi said.

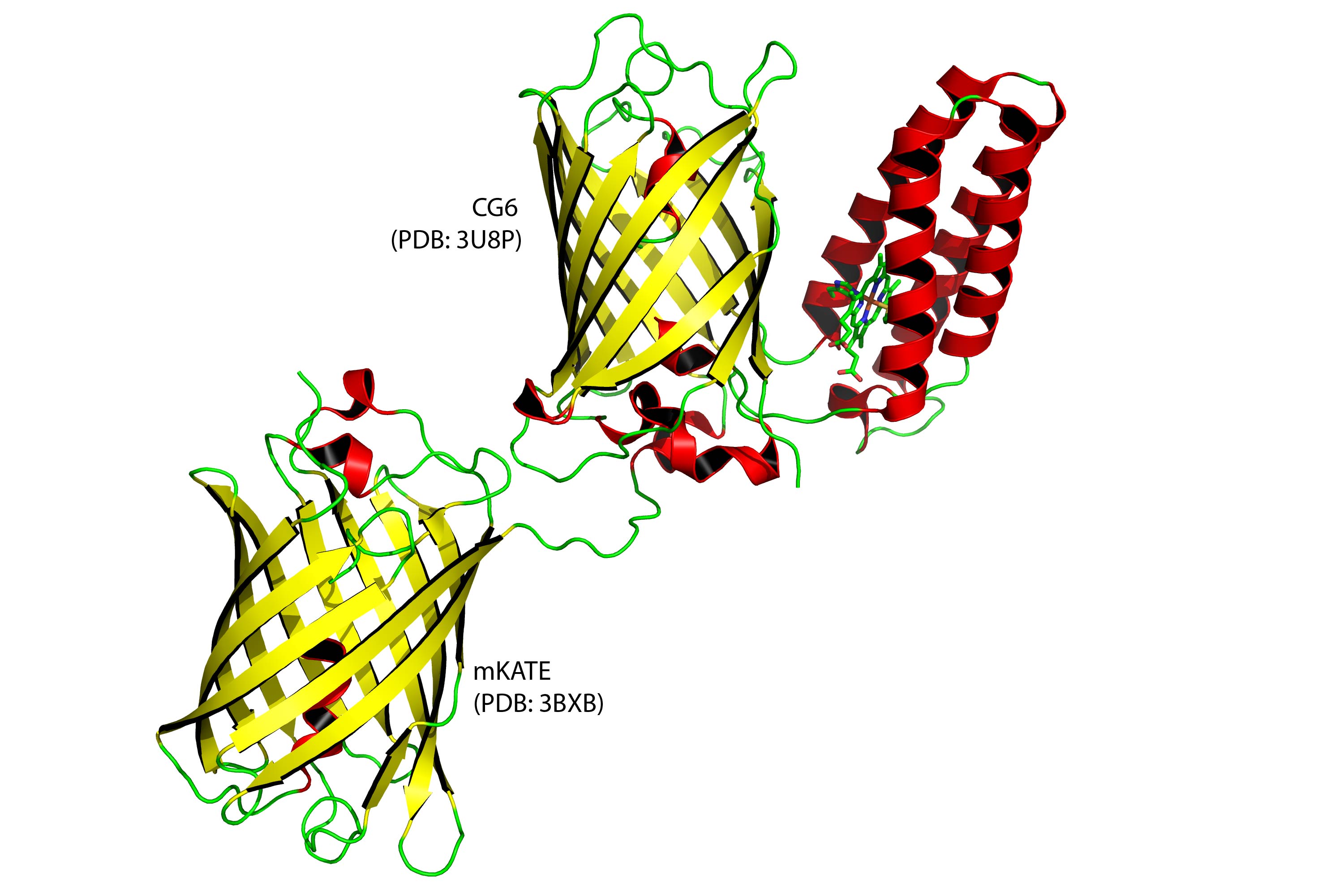

Graphic rendering of a ratiometric sensor (upper right pair). It is a combination of a bacterial protein (depicted in red) that attracts heme and a fluorescent protein (depicted in yellow). They could be analogous to a person holding a lamp while attracting hemes to block it’s light. Lower left protein is an “internal standard” fluorescent protein, a type of experimental control. (Credit: David Hanna with PyMOL/Georgia Tech)

Not having a sensor was one reason labile heme has not been previously observed, so the Georgia Tech researchers used a ratiometric fluorescence approach to design one that could be described a little like the comic book superhero “Green Lantern.”

As hemes are attracted to him like, say, fans, they become clutter, said Reddi, the paper’s principal investigator. “He holds them in front of his green light, and they block it, making it appear dimmer.”

“Ratiometric fluorescent techniques have been around for a while, but our technique is new, because it specifically senses heme,” Reddi said. “We took a heme binding protein from bacteria and clipped it onto to green fluorescent protein.”

A microscope focuses on baker’s yeast cells glowing from ratiometric sensors tailored to track the movements of heme, a toxin that is essential to cell functions. (Credit: Rob Felt / Georgia Tech)

The researchers used a blue laser to charge up the lamp part of the sensor protein pair like a glow-in-the-dark sticker, then it re-emitted the green light. “You see this green image disappearing and reappearing depending on how much heme is available,” Reddi said. “You can see what’s happening in real time.”