Researchers from Harvard University developed what they tout as the 1st entirely 3D-printed organ-on-a-chip with integrated sensing. The heart-on-a-chip was quickly manufactured by a fully automated, digital procedure and allows researchers to collect data for short-term and long-term studies.

Researchers from Harvard University developed what they tout as the 1st entirely 3D-printed organ-on-a-chip with integrated sensing. The heart-on-a-chip was quickly manufactured by a fully automated, digital procedure and allows researchers to collect data for short-term and long-term studies.

The team, who published their work in Nature Materials, hope that one day this approach may allow researchers to design organs-on-chips that match the properties that characterize a particular disease or an individual patient’s cells.

“This new programmable approach to building organs-on-chips not only allows us to easily change and customize the design of the system by integrating sensing but also drastically simplifies data acquisition,” 1st author Johan Ulrik Lind said in prepared remarks.

“Our microfabrication approach opens new avenues for in vitro tissue engineering, toxicology and drug screening research,” coauthor Kit Parker added.

Organs-on-chips are a promising alternative to conventional animal models, as they can mimic the structure and function of native tissue. But the fabrication and data collection process for these alternative models are normally expensive and labor-intensive. Data collection requires microscopy or high-speed cameras, while manufacturing is done using a complex, multi-step lithographic process.

“Our approach was to address these two challenges simultaneously via digital manufacturing,” coauthor Travis Busbee said in prepared remarks. “By developing new printable inks for multi-material 3D printing, we were able to automate the fabrication process while increasing the complexity of the devices.”

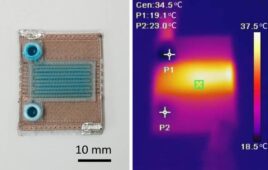

The team created six different inks that integrate with soft strain sensors within the tissue. In a continuous procedure, the team printed the heart-on-a-chip with integrated sensing. The chip has multiple wells with separate tissues and sensors, which allows researchers to study many samples at once.

“We are pushing the boundaries of three-dimensional printing by developing and integrating multiple functional materials within printed devices,” coauthor Jennifer Lewis explained. “This study is a powerful demonstration of how our platform can be used to create fully functional, instrumented chips for drug screening and disease modeling.”

“Researchers are often left working in the dark when it comes to gradual changes that occur during cardiac tissue development and maturation because there has been a lack of easy, non-invasive ways to measure the tissue functional performance,” Lind said. “These integrated sensors allow researchers to continuously collect data while tissues mature and improve their contractility. Similarly, they will enable studies of gradual effects of chronic exposure to toxins.”

“Translating microphysiological devices into truly valuable platforms for studying human health and disease requires that we address both data acquisition and manufacturing of our devices,” Parker added. “This work offers new potential solutions to both of these central challenges.”