More than five months into a successful recovery from surgery to remove a golfball-sized meningioma, medtech industry veteran Bill Betten reflects on lessons learned.

Bill Betten, Betten Systems Solutions

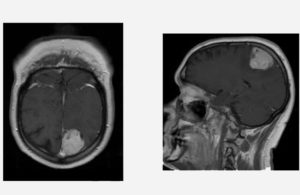

MRIs of the tumor in medtech veteran Bill Betten’s head. [Image courtesy of Bill Betten]

Fast forward to today, and I’m months into a mostly successful recovery from surgery that removed what turned out to be a benign tumor. I have a very interesting scar slowly healing on my head. I’m still waiting for my new superpower to show up now that I’ve got the extra room in my brain, but perhaps my personal journey will be the reward in itself.

While my observations certainly aren’t going to reform health care, the process certainly gave me a different view than my usual product development or technology role, and I hope you gain a new perspective as well.

Just to tell you more about myself, I’m a physicist and an electrical engineer who’s had the great pleasure of working for decades on product development for some of the world’s largest companies as well as startups. While much of my career was spent in and out of hospitals working for medical device development companies, that experience did little to prepare me to be a patient or user of many of the products and services on which I’d worked over the years.

[Bill Betten discussed his story at DeviceTalks Minnesota in September, as well as in a recent podcast with MDO editor Chris Newmarker. Discover more great medical device stories at DeviceTalks West, Dec. 9–10 in Santa Clara, Calif.]

The discovery

My earliest medical experiences went back to my time at 3M in the late 1980s. I worked on hearing aids, blood perfusion systems, and surgical systems among other things, and in the 90’s I was an interface program manager figuring out the early days of connected medical devices, teleradiology, and the DICOM interface that was supposed to ensure that expensive imaging systems play together. Our work included collaborating with imaging modality partners to send digital X-ray images from the USS George Washington aircraft carrier to Bethesda Naval Hospital and Walter Reed Army Medical Center.

I ultimately migrated to the world of much smaller monitoring devices, but MRI has always fascinated me. I’ve been honored over the years to speak with leaders in the field including Dr. Raymond Vahan Damadian, the inventor of the first MRI and founder/CEO of Fonar, and Doug Dietz, innovation architect at GE Healthcare. I also recently worked for a company that provides much of the internal precision cabling and connectivity within MRI systems for major manufacturers.

Little did I anticipate, however, that I would one day land myself inside the confining tube of an MRI — the result of finally checking up on a left leg that would “go to sleep” for minutes with a pins and needles sensation. My general physician in February had forwarded me to a neurologist who was heading toward the same diagnosis: pinched nerve. I thought the steroids I was already taking were causing some low-grade headaches, but I mentioned the headaches anyway. The neurologist listened and told me that headaches in someone over age 40 with vision issues typically suggested an MRI. I asked when, was told that there had been a cancellation, and 10 minutes later was having my first MRI ever.

The MRI whirred, banged and clicked its way through the 45-minute process of flipping my molecules with a magnetic field and then reading the results for a look inside my head. I knew that the inside of an MRI was truly confining and full of strange noises, but it’s another thing to actually experience. All my memories about MRI flashed through my head as I lay in the tube, staring up, listing to late ‘70s rock music as I wondered what was going to happen with me.

I got dressed and saw the neurologist coming in right away to speak with me — not a normal situation. She said it was a “probably” non-malignant type of tumor called a meningioma that forms on membranes that cover the brain and spinal cord just inside the skull. Technically it isn’t a brain tumor as it doesn’t usually engage the brain directly; it is just a tumor that is in the head. At that particular point in time, however, that wasn’t much of a distinction. The words “head” and “tumor” are still pretty scary when used together. You go, “Wow, what does this all mean?”

“It’s been there a decade at least — growing,” the neurologist said.

Finding the right surgeon

The diagnosis immediately sent me into an information-gathering mode, looking up the details of meningiomas and starting down the path of figuring out what to do next. Fortunately, health insurance was not an issue as one of the benefits of being married to a retired teacher is the ability to continue benefits, albeit at a rather stiff price. I needed to ensure at a minimum that both the surgeon and facility were covered, but our premium coverage made it likely they would be.

My immediate focus was on contacting neurosurgeons. Living in Minnesota certainly facilitates — or perhaps confuses — the process since we have excellent internationally recognized facilities. After compiling a list of about 10 surgeons I decided that I wanted to get at least two opinions. Arranging the appointments included the frustrating experience of just how much the healthcare system still lacks interoperability. I’ve been promoting the virtues of telemedicine for over 25 years, but here I was filling out transfer forms, listing FAX numbers because email was unacceptable, and even picking up a disk of images from the exam myself as a backup.

The first surgeon with whom I met made the interesting comment that started this article. Upon my inquiry (and a good laugh), he pointed out that my symptoms were a bit atypical for this size of the tumor as I did not show any expected signs of “left-side weakness” that would have been expected based on the size and location of the tumor. We discussed the MRI, medical technology, and some common people we knew at the Mayo Clinic where he had trained years before. He generally walked me through the options. It’s one thing to have a dispassionate conversation about medical technology as a developer, but a very different process when you’re the subject of the conversation. We discussed some timing concerns, but his recommendation was certainly surgery, and he recommended getting it relatively soon. He was calm, collected, and very engaging in the conversation. When we walked out my wife commented that “he really thought of you as a person.” He further demonstrated this when I got a call from him after hours the next night as I had left a message with a few questions for his nurse. He knew that I was getting another opinion, but his message was that getting treatment at all was more important than whether he did the surgery. Spending an extra 20 minutes of his “off-time” answering my questions was greatly appreciated.

Two days later I met with surgeon No. 2, a very experienced surgeon who had probably done 10 times the procedures of the first and was undoubtedly qualified. The visit was professional, factual and addressed my questions. When I inquired about going down the road to the Mayo Clinic, where I have been doing collaborative work for decades, or the University of Minnesota hospital where I’m engaged on a pediatric board, he noted that my case simply wasn’t that interesting nor was it necessary. He’d trained in a research institution and pointed out that this was relatively straightforward and would likely go as a training case for a resident. He saw no need to go to those lengths as this just wasn’t that challenging. His words were reassuring in their own way, but on the other hand, I’m not sure there is such a thing as “minor” brain surgery unless perhaps it is being done on someone else.

So, which of these two qualified surgeons did I choose? When it came down to it, we decided to go with the first surgeon, the one who viewed me as a “person, not just a patient.”

The surgery

Underneath the hood. NOT minimally invasive. [Image courtesy of Bill Betten]

On the day of surgery, I arrived for a pre-operative MRI at 5 a.m. in order to prepare for surgery tentatively scheduled for 7:30 a.m. This MRI was a bit different from my diagnostic scan as this involved the placement of interesting little targets all over my head in strategic locations, providing a “GPS” system for precise mapping of the tumor location. At this point I was marked up with a pen, shaved, then adhesive waypoints fastened to my head making me look a bit like Frankenstein’s monster. Another 45-minute MRI and a trip back to my pre-op site later, and I’ve got the surgical team walking in to say hello and introduce themselves. I took particular care to make sure that they knew who I was, even mentioning the somewhat macabre experience of doing some final device development work at a Mayo Clinic cadaver lab the day before surgery and pointing out that I was very eager to come out of this surgery in a positive fashion.

The anesthesiologist must have done a great job of prep as the last thing I remember was being wheeled around the corner following the team and that was it. I woke up 8 hours later. I came out of anesthesia “hangover” free and relatively coherent, certainly much different than my only previous surgical procedure more than 20 years ago. To make a long story short, the surgery went well, taking a long time due to tumor consistency being that of an eraser and a bit challenging to remove. The good news was that they removed almost 98% of the tumor, with some need to only heat treat the remainder due to its proximity to a large vein in the brain.

ICU and recovery

A “connected patient” [Image courtesy of Bill Betten]

The ICU is definitely not designed for ease of recovery. The staff poked, prodded and tested me every hour during the night. In addition, since I used to be a fairly consistent runner, my natural resting heart rate tends to be in the 50’s, sometimes dropping into the high 40’s when asleep, so the alert went off every time that happened. The only saving grace was that being fully hooked up meant I was connected via a catheter, so at least I didn’t have to worry about going to the bathroom. I thought back to all of the meetings I had over the years with remote monitoring companies discussing all kinds of devices for monitoring and how it would revolutionize health care. Years later, we’re still being poked and prodded, including the thermometer under the tongue and a blood pressure cuff blowing up every hour for measurements. After a night of this, I resolved to do everything I can to facilitate the evolution to wireless wearables and more friendly sensors.

After that “interesting” night in ICU, the discussion focused on whether I could transfer to the med/surgical unit, where I’d likely only need to be monitored every 2 hours. They’d let me eat some real food, too. In order for that move to happen, I had to go through both a cognitive assessment and a physical evaluation. Less than 24 hours after surgery, I was nervously going through an evaluation of my mental capabilities — a scary proposition because who knows what transpired while I was operated on. Was I the same person coming out as the one going in? But I passed the test and got a larger room with a great view and even a bathroom.

Prior to surgery I was told to expect to stay in the hospital for a total of four to five days, depending upon any complications, infections, mobility issues, etc. However, my surgeon called me Saturday morning after the second night in the hospital, asked how I was feeling, and mentioned that the initial assessments seemed to be very positive. He asked if I would be interested in departing the hospital that day, less than 48 hours after surgery. While a bit concerned about the rapid exit, I recognized that recovery at home is less costly and more conducive to rest — as long as there’s an appropriate support system and precautions. Healthcare experts, in fact, know that a more relaxing home treatment and recovery has substantial benefits, providing both a decrease in cost and an increase in quality of life. My wife, and my “alpha” sister who had come to town, were a bit panicked at the news because they had expected a bit more time to set up the new “recovery” room in our first floor sunroom so I wouldn’t have to climb stairs. But 48 hours after surgery I on my way home to my personal recovery room.

Reflections

While the journey through the system was complex, arduous, and a bit scary as a participant rather than an observer, I was impressed by the people in the system. I am a technology person and have been involved in many of the technological improvements that proved to be valuable in my care. However, I was reminded at every step — from help identifying potential surgeons, the interviews, and the care in ICU and the med/surgical floor — that it is still about the people, not just the technology.

While I’m not naming the individuals involved, I have the utmost of respect and thanks to the doctors, staff, and facilities at Regions Hospital in St. Paul. They uniformly made me feel like a person not an object. Perhaps I went out of my way to connect with them as well given my background, but it made me miss that care environment just a bit, particularly when I got the follow-up welcome home card signed by them. People do make a difference.

As for me, I’m going back to work on medical technology, working with partners to develop tools to ease pain and suffering. Technology is the great enabler, and I believe it will continue to ease care for chronic illnesses, elder care and assisted living, and perhaps even one day the various maladies afflicting us. My trip through the health care system certainly gave me a much better appreciation of the medical system not just as a developer but as a person.

Bill Betten is the president of Betten Systems Solutions, a product development realization consulting organization based in Minneapolis-St. Paul. Betten utilizes his years of experience in the medical industry to advance device product developments into the medical and life sciences industries, helping clients to develop innovative medical devices and adapt to a changing environment. Betten most recently served as director o business solutions for Devicix/Nortech Systems, a contract design and manufacturing firm. Bill has also served as VP of business solutions at Logic PD, medical technology director at TechInsights, VP of engineering at Nonin Medical, and in a variety of technology and product development roles at various high-tech firms, including Honeywell and 3M.

The opinions expressed in this blog post are the author’s only and do not necessarily reflect those of Medical Design and Outsourcing or its employees.