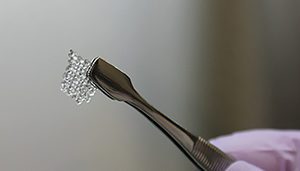

Northwestern University researchers 3D printed gelatin to create a scaffold for a bioprosthetic mouse ovary [Image courtesy of Northwestern University]

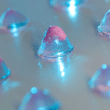

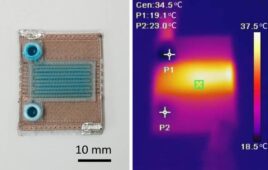

The Northwestern researchers successfully 3D printed a bioprosthetic mouse ovary that ovulated when implanted inside a live mouse. Mice with the bioprosthetic ovaries were able to give birth to live pups, and even produce milk for them thanks to hormones produced by the 3D printed ovaries.

“This research shows these bioprosthetic ovaries have long-term, durable function,” said Teresa K. Woodruff, a reproductive scientist and director of the Women’s Health Research Institute at Northwestern’s Feinberg School of Medicine.

“Using bioengineering, instead of transplanting from a cadaver, to create organ structures that function and restore the health of that tissue for that person, is the holy grail of bioengineering for regenerative medicine,” Woodruff said in a news release.

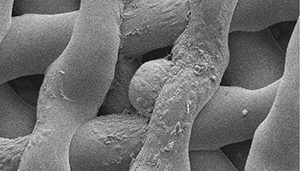

An immature egg cells wedges into the 3D printed scaffold. [Image courtesy of Northwestern University]

“Most hydrogels are very weak, since they’re made up of mostly water, and will often collapse on themselves. But we found a gelatin temperature that allows it to be self-supporting, not collapse, and lead to building multiple layers. No one else has been able to print gelatin with such well-defined and self-supported geometry,” said Ramille Shah, assistant professor of materials science and engineering at McCormick and of surgery at Feinberg.

3D printing allowed the researchers to imitate the complex soft tissue structures of actual ovaries. The gelatin “skeleton” or “scaffolding” provided an optimal geometry for follicles, or immature eggs, to wedge within the scaffold. The open structure enabled the egg cells to mature and ovulate, and for blood vessels to form within the implant – creating a mechanism for hormones to circulate within the mouse.

A research mouse with a green pup produced from an egg from the bioprosthetic ovary. Researchers used eggs that produced green pups, in order to tell them apart from the control group. [Image courtesy of Northwestern University]

“What happens with some of our cancer patients is that their ovaries don’t function at a high enough level and they need to use hormone replacement therapies in order to trigger puberty,” said Monica Laronda, co-lead author of the research and a former post-doctoral fellow in the Woodruff lab.

“The purpose of this scaffold is to recapitulate how an ovary would function. We’re thinking big picture, meaning every stage of the girl’s life, so puberty through adulthood to a natural menopause,” Laronda said.

[Want to stay more on top of MDO content? Subscribe to our weekly e-newsletter.]

Do you mind if I quote a few of your articles as long as I provide credit and sources

back to your blog? My blog is in the exact same area of interest as yours and my

users would really benefit from some of the information you

provide here. Please let me know if this alright with you.

Thanks a lot!

Feel free to post a bit and link back to the original article. Thanks!