The health system’s medical and engineering staffs had to devise their own solutions for lab gear, PPE and operating room air decontamination.

[Image courtesy of Mayo Clinic]

While this may serve as little comfort, hospitals in regions getting hit by the new wave of the deadly virus do have the benefit of seeing how hospitals in the Upper Midwest and the Northeast managed the pandemic.

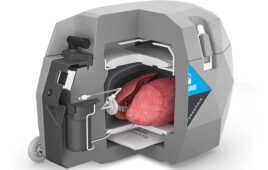

One of the easiest — or at least most evident — lessons available is the use of additive manufacturing or 3D printing. Mayo Clinic and other hospital systems, including Beth Israel Lahey in Boston, used their 3D printers to produce critical personal protective equipment (PPE) such as masks and face shields, as well as swabs used with COVID-19 diagnostic tests. But hospitals looking to secure vital PPE need to be aware that Mayo’s success came as much from an organizational commitment to innovation as from an acquisition of 3D printers.

During a DeviceTalks Tuesday presentation in May, a team from Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. — three engineers and a physician — spoke about the institution’s success in overcoming supply shortages during the first dark days of the pandemic in March and April. While COVID-19 never hit Minnesota as hard as it did the Northeast, Mayo engineers, physicians and other hospital staff worked in overdrive to ensure Mayo healthcare providers had the necessary tools to treat sick patients. [You can watch the DeviceTalks Tuesdays presentation with these Mayo Clinic experts here.]

Amy Alexander, a senior biomedical engineer who works in the Mayo Clinic anatomical modeling lab with its director, Dr. Jonathan Morris, said 3D-printing technology can give hospitals a backup plan if traditional supply routes dry up.

“I’ve been thinking 3D printing was going to disrupt the supply chain for a couple of decades now,” Alexander said. “It will be exciting to see how healthcare institutions take advantage of this option. It’s almost like doomsday preppers. It’s not that extreme, of course, but you can be prepared for that time when maybe you can’t get an order through Amazon in two days. People are looking at additive manufacturing now more than they were before, which is huge.”

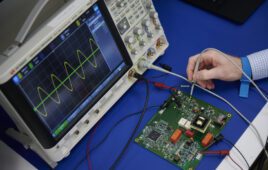

The potential for 3D printing is considerable, but it must be supported by deep engineering and healthcare expertise. Mark Wehde, chairperson of Mayo Clinic’s division of engineering, said Mayo has a “very robust” safety/risk process and a well-defined project management.

“We have all the pieces in place that allow us to safely develop devices that can be used in patients,” Wehde said.

Organizations that have engineers but don’t have an established process are at a disadvantage, according to Wehde. He recalled an example in which a valve 3D-printed in Italy was being touted as a solution for the ventilator shortage as it would allow two patients to be connected to the same ventilator.

“I asked our respiratory therapy staff if they had any interest in that and they said [those valves are] probably part of why the mortality rates are so high,” he said. Mayo passed on the valve.

In addition to working with internal experts, Mayo Clinic worked with companies including Stratasys and Medtronic to manufacture more than 10,000 masks and face shields, according to Morris, who is also a consultant in diagnostic radiology. To do this, the health system had to reassign 10 employees from its quieted radiology department to a conference room where they made an additional 22,000 masks. Mayo also retrained 30 other employees to work in a traditional manufacturing lab to make face shields non-stop over three shifts.

Mayo Clinic’s success in generating supplies could create a tempting path for others to follow. But executives note the hospital system came into the pandemic with a long streak of developing devices. Mayo boasts 7,000 ft2 of manufacturing space within its Rochester campus, including a printer capable of manufacturing titanium implants. The units are located near clinicians, so engineers and physicians can collaborate.

“I don’t know that everyone should have something like this. Just like every hospital doesn’t have robotic surgery,” Morris said. “You know, there are centers that are equipped to have multidisciplinary teams like this. I mean, Mayo Clinic has a huge infrastructure because of the size and scope of problems we handle. Whereas other hospitals and the health system will never have that because they don’t need to have that.”

Sean McEligot, section head of technology and development in Mayo’s engineering division, said hospital systems should be building out their teams now, so clinical and engineering professionals will be in place to collaborate on future projects. Through the pandemic, Mayo has finished over two dozen projects and has an equal amount ongoing.

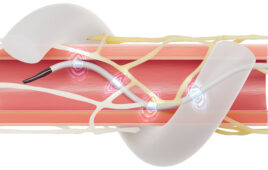

McEligot said he sensed a pattern in the projects as they came in waves. The first wave centered around lab safety and efficacy, requiring safety shields, totes and racks for Mayo labs. The second wave required new respiratory therapies for patients. PPE demand came in the third wave, forcing Mayo to develop its own PPE. The fourth and fifth wave focused on controlling the airborne spread of the disease and creating new ways to clear potentially contaminated air out of operating rooms.

“I think if there’s a next pandemic, we have the recipe,” he said. “[The team] is focused and ready to go.”

[You can watch the DeviceTalks Tuesdays presentation with these Mayo Clinic experts here.]