The two “Rs” — regulatory and reimbursement — are critical elements of the environment in which a medical device product is developed.

Bill Betten, Betten Systems Solutions

This is the fourth in a series of articles that discusses the design of innovative products in the highly regulated medical environment. But the “environmental” factors of regulatory and reimbursement actually influence all stages of the development. They impact everything from the process to the plan and the requirements. You need to consider their influence at the earliest stages of the development effort.This series focuses on the definition and execution of product development activities post-funding and includes the following:

- Idea – Without it, nothing to be developed

- Process – The structure for development

- Plan – The blueprint

- Requirements – The details

- Regulatory/Reimbursement – Critical to the medical device space (The article you’re reading.)

- Verification/Validation – The right product doing the right thing

For the purposes of this article, I’ve included regulatory and reimbursement together, but they impact the product in very different fashions, particularly when international markets are considered.

How to handle regulatory

Let’s first consider the regulatory impact on the product development process. While I’ll use the U.S. and the FDA as the example, virtually every other market in the world has some form of regulatory body that impacts the medical product development process. The FDA is responsible for protecting the public health by assuring the safety, efficacy and security of human and veterinary drugs, biological products, medical devices, our nation’s food supply, cosmetics and products that emit radiation. They are also responsible for advancing public health by enabling medical innovations and by helping the public get the information required for the use of medicines and foods for the maintenance and improvement of health.

First, what constitutes a medical product? Section 201(h) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act defines a medical device as:

“… an instrument, apparatus, implement, machine, contrivance, implant, in vitro reagent, or other similar or related article, including any component, part, or accessory, which is … [either] intended for use in the diagnosis of disease or other conditions, or in the cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease, in man or other animals … [or] intended to affect the structure or any function of the body of man or other animals.”

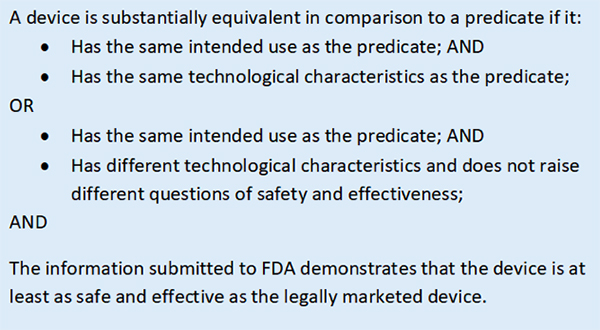

Medical devices are classified into three classes, increasing in regulatory control from Class I to Class III. Device classification depends upon the product’s intended use, indications for use, the risk to the patient, and finally, the risk to the user. The FDA reviews device applications in one of two primary processes, the Premarket Notification 510(k) clearance and the Premarket Approval (PMA). In general, most Class I devices are exempt from the 510(k), while most Class II devices require 510(k), and most Class III devices require Premarket Approval (PMA). The 510(k) is a premarket submission to the FDA that demonstrates that the new device to be marketed in the U.S. is “substantially equivalent” to a predicate device already being legally marketed in the U.S. and that doesn’t need the PMA.

Here’s the decision process for determining substantial equivalence for your medical device. [Image courtesy of FDA]

In either case, a submission and review by the FDA must be conducted and clearance received before the device can be marketed in the U.S. While the impact of the regulatory process is felt throughout the development and manufacturing processes for the product, the immediate impact from a schedule perspective is that the targeted time to clearance for a 510(k) is approximately 90 days, while FDA regulations provided 180 days to review a PMA. However, particularly in the case of a PMA, these determinations can take much longer as questions, reviews and additional information need to be provided. According to the FDA, in 2015 PMA clearances averaged 209 days and 510(k) clearances averaged 109 days.

An additional clearance process is the “de novo” application, created in 1997. This approach is for devices that are automatically classified as Class III devices because no substantially equivalent predicate exists for them. It is intended to help avoid a lengthy and costly PMA submission for devices with low or easily mitigated risks. In 2012 the process was simplified to allow the applicant to directly submit a de novo application for the FDA to review and either approve or deny the application. While the targeted decision date is within 60 days of submission, the uncertain nature of the classification can lead to additional discussion and delays as the decision is reached.

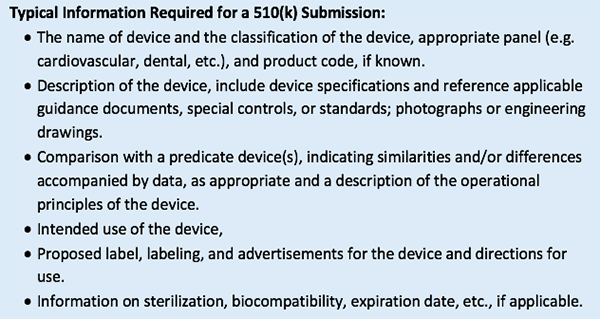

The impact of any of these processes on your development effort needs to be considered at the beginning of the project as it ripples through everything. Typical information required in a 510(k) submission is listed below:

In addition, the FDA requires several other sets of documentation to be compiled as part of the development process. The Design History File (DHF) contains the records necessary to demonstrate that the design was developed in accordance with your approved design plan and established quality system. This also includes the design inputs and outputs, as well as design verification and validation protocols and results, essentially everything that went into the design of the product. This is much easier to produce and record if it is done as an integral part of the design and development process. The Device Master Record (DMR) includes everything that is necessary to build and test the device, including much of what is contained in the DHF, but extending much further by incorporating the manufacturing, test, quality, packaging and documentation that goes with the device. The Device History Record (DHR) contains everything that you did to make the device. The FDA requires that the manufacturer “shall establish and maintain procedures to ensure that DHR’s for each batch, lot, or unit are maintained to demonstrate that the device is manufactured in accordance with the DMR and the requirements of this part.”This is only the most cursory of overviews of the regulatory process for medical devices, but it should be clear that the impact of regulatory oversight extends into virtually every aspect of the design, manufacturing, test and support of medical products. A quick review comparing general consumer-oriented regulations and quality requirements to those required for a medically regulated product easily shows an overhead of at least 50% in additional requirements, standards and testing, which results in much additional effort, cost and schedule, not including the impact of lengthy and costly clinical trials.

How to handle reimbursement

The second of the two “Rs,” reimbursement, while having much less of an impact on the design and manufacturing processes is no less important to the overall success of your product introduction as it addresses a vital question: “Who pays for your product?” This requires data, discussion and negotiations by stakeholders, including the providers and payers. Coverage, coding and payment are the three major components of the reimbursement process.

Coverage is in the realm of the payers and describes the types of services and procedures which will be paid. These typically are those services and procedures that are considered “medically reasonable and necessary.” Coverage can vary from plan to plan depending upon what each payer decides to cover.

Coding refers to the intricate system of descriptions that describe the procedures being performed. The International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10) is the clinical cataloging system owned and published by the World Health Organization that went into effect for the U.S. healthcare industry on Oct. 1, 2015. The healthcare industry uses ICD codes to properly note diseases on health records, to track epidemiological trends and to assist in medical reimbursement decisions. ICD-10 is split into two systems in the U.S.: ICD-10-CM (Clinical Modification), for diagnostic coding (68,000 codes), and ICD-10-PCS (Procedure Coding System), for inpatient hospital procedure coding (87,000 codes). This level of granularity should help enable big data analytics to assess procedures being performed, although at the expense of greatly increased complexity.

Even with coverage determined and a code established, the payment may not necessarily cover the full cost of the treatment or service being rendered, since each payer may negotiate with providers for pricing specific to their overall plan. However, without coverage and a code, no payment will be made. Beyond the issue of getting paid for your product, however, additional implications of the reimbursement decisions exist. These include assessment of what your product does, who it is intended for, its efficacy at solving a specific problem, and its value. The understanding of whether you will be working to establish a new code (difficult and time-consuming as well as requiring significant clinical evidence) or whether your product will be designed to fit under existing descriptions may impact the design of the product and will certainly impact the intended use statements and documentation associated with your product.

Conclusion

Given the impact that regulatory and reimbursement can have on the design, cost and schedule of your product, it is recommended to begin the dialogue early in your product development cycle. These areas are two in which outside consulting resources are often necessary due to the specialized and changing nature of the subject matter. The development environment for medical devices is substantially different than commercial devices since the regulatory process helps ensure that your claims for the device are accurate and that the product is safe. The payment for your product and service also is distinctly different in that the cost of goods to produce the product and the traditional market influences on pricing of consumer products is not directly related to the price established by the reimbursement process.

Now let’s examine how the two “Vs”, verification and validation, are a critical part of the product development process>>

Bill Betten is the president of Betten Systems Solutions, a product development realization consulting organization. Betten utilizes his years of experience in the medical industry to advance device product developments into the medical and life sciences industries. Betten most recently served as director of business solutions for Devicix/Nortech Systems, a contract design and manufacturing firm. He also served as VP of business solutions at Logic PD, medical technology director at TechInsights, VP of engineering at Nonin Medical, and in a variety of technology and product development roles at various high-tech firms.

The opinions expressed in this blog post are the author’s only and do not necessarily reflect those of MedicalDesignandOutsourcing.com or its employees.