You would think that inhalable insulin should be a million-dollar idea, right? No longer would diabetics have to worry about regular injections or an insulin pump to keep track of. Administering the medicine would be simple and virtually painless—a diabetic’s dream.

But both major efforts to successfully get an inhalable insulin device into the market in the last decade have failed. Miserably. And these aren’t small projects coming from ambitious startup companies: the first major attempt was made by Pfizer in 2006, and the second by Sanofi in early 2015.

Pfizer partnered with Nektar Therapeutics to develop Exubera, dry powder form of insulin delivered with an inhaler. Since it was the first type of insulin that didn’t require injection, analysts projected one to four billion dollars in annual sales. But after nine months of sales, the product had only garnered 12 million dollars.

Many attribute Exubera’s failure to Pfizer. They didn’t contact Nektar at all before breaking the news, so Nektar learned about it via the newswire, just like everyone else. Some believe Pfizer thought Exubera would sell itself, and marketing became inadequate as a result—reasons cited include a lack of samples, late TV ads, and a general lack of exciting advertising. Others cite that physicians simply didn’t want to take on a new product.

But most agree that the issue lied in the inhaler’s design specifically its size. Exubera was about as large as a flashlight, and even larger when expanded to ready position. The inhalation technology wasn’t the issue—to operate, the user simply loads small blister packets of insulin for each dose and triggers the mechanism for inhalation.

The problem was that many were embarrassed to use Exubera in public because it looked like a bong. That one’s on Nektar: they were the one to come up with the inhaler design.

I can see why someone might have reservations about inhaling this in public. (Credit: Science Museum Group)

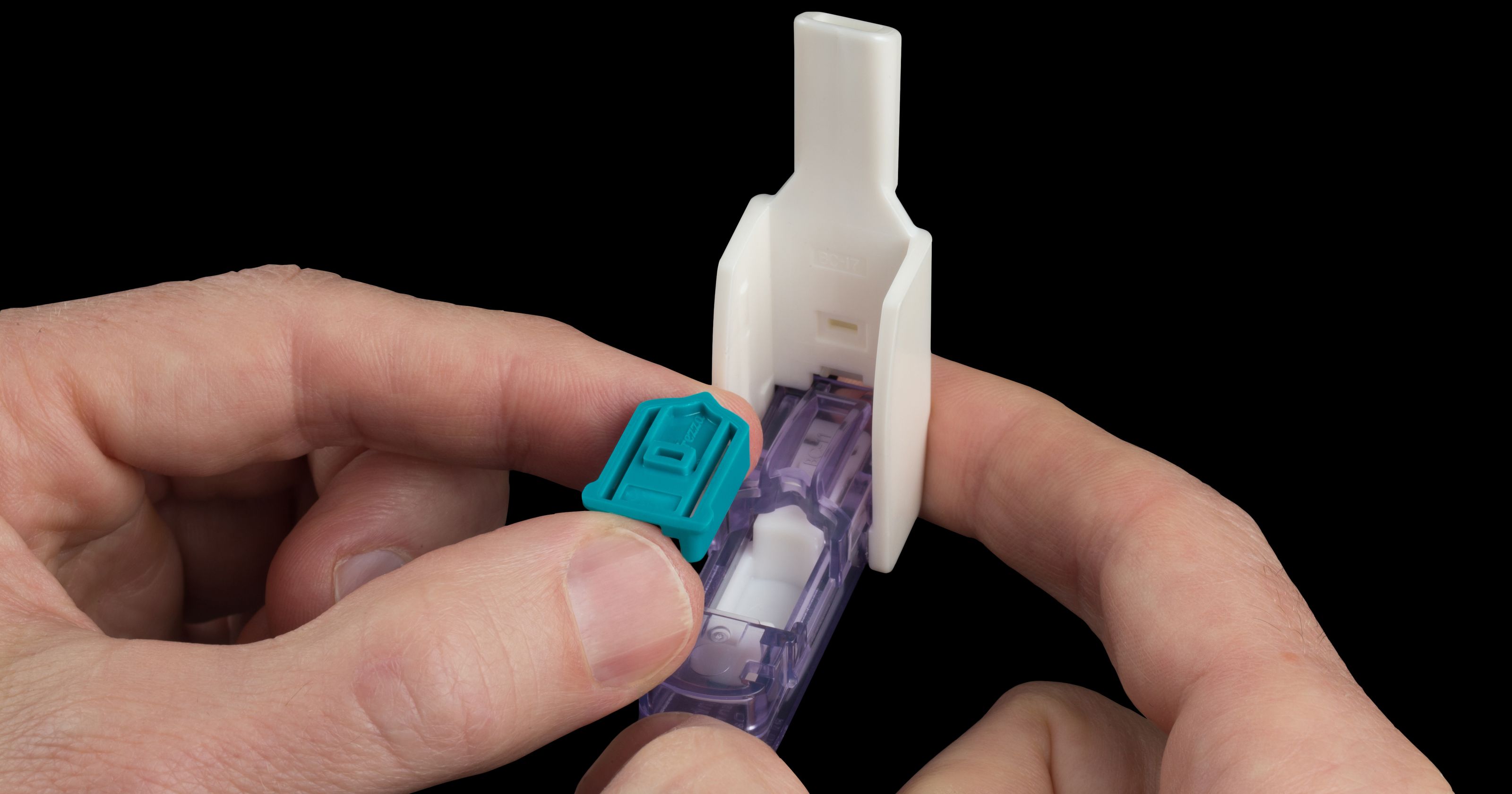

Fast forward almost a decade to February 2015, when Sanofi launched Afrezza, its iteration of an inhalable insulin device, this time developed by MannKind. All signs pointed to it being a success: the delivery device was smaller (about the size of a whistle) and Afrezza was marketed more aggressively than Exubera.

But a month ago, Sanofi announced it was backing out of the partnership due to poor sales—only about five million dollars in the first nine months of marketing. It performed more poorly than Exubera, and the issue of the product being mistaken for a bong couldn’t have happened this time. It was much less conspicuous!

Pictured: much less likely to be confused with a bong. (Credit: MannKind)

For starters, inhalable insulin carries some risks. Exubera exhibited some of the same issues: inhaled insulin can cause constriction of the lungs’ airways in patients with COPD and asthma.

However, the main issue (once again) looked to be challenges with the technology’s adoption by the healthcare community. One physician cited his reasoning in July 2015 in BioPharma Dive: “I would not write it for two reasons: 1) The Exubera problem with the lungs and Afrezza’s boxed warning regarding the same issue, and 2) What a pain it is trying to change a patient from the needle-based insulin to inhaled insulin because of dosing. A mistake in equivalency can mean hypoglycemia. I imagine that’s why most doctors will not switch patients. The only time I would consider prescribing Afrezza would be for a new patient that I can get used to it slowly, or someone who is very scared of needles.”

Sanofi will continue marketing Afrezza until April 2016, but after that MannKind is on its own. It’s really a shame—inhalable insulin delivery would be a breath of fresh air for diabetics who are administered daily injections.

The lung problems should be fixable: pharma companies developing the powdered insulin need to spend more time in the lab finding a solution that doesn’t impede lung function. But adoption by the healthcare community is a major hurdle that can’t easily be resolved, and has so far derailed two insulin inhalers put out by very large companies. And unfortunately, unless this is resolved, inhalable insulin may never catch on.

What do you think can be done to help the healthcare community embrace inhalable insulin? Comment below!