The viscosity of blood is widely regarded as an indicator of general health. When a blood vessel is damaged or broken, blood loss needs to be minimized, so a series of reactions begins to form a blood clot. A number of medical conditions adversely affect this process and in these cases patients are often prescribed an anti-coagulant. Health management for those taking anti-coagulants often involves the weekly monitoring of blood clotting time to ensure that drug dosage is appropriate.

The devices are simple to use with a clear display and large buttons. They are comfortable in the hand and the home use device is a discrete size.

Existing hand held devices work by inducing a chemical reaction that is picked up by electrodes coated with compounds. Microvisk developed a new technique that stems from research on micro-technology and harnesses the power of micro-electronic mechanical systems (MEMS).

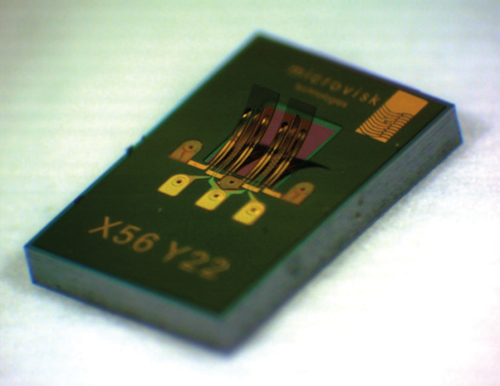

Microvisk’s MEMS-based micro-cantilever devices are produced on a wafer-scale where thousands of identical microchips are processed together as flat structures on the surface of silicon wafers. Only at the final stage of production are the micro-cantilevers released to deflect above the supporting surface, forming truly 3D microstructures. Such highly deformable and flexible micro-cantilevers, controlled by complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) type signals, form the heart of Microvisk’s fluid micro-probe used in determining the rheometric properties of minute (nanolitre volume) samples. When a current is passed through the structure each layer deflects in a different way. As one structural layer expands more, another expands less, which leads to each cantilever moving up and down in response to immersion in a gas or in a liquid such as blood. The speed of blood clotting and its rheometric changes associated with the clotting process can therefore be monitored in a one-stage process based on physics rather than chemistry.

Microvisk uses MEMS on a disposable strip which incorporates a small cantilever to measure viscosity.

Dr. Slava Djakov, inventor and Sensor Development Director of Microvisk, explained, “Other cantilever designs typically used in atomic force microscopy (AFM) applications or in biological research for probing and assessing DNA, protein, and aptamer bindings with drugs or antibodies usually use crystalline silicon (cSi) rigid cantilevers. Because of their rigidity, cSi and similar structures are very delicate, brittle, and have limited movement. Although cSi cantilevers can be very sensitive through actuation in resonant mode, the restricted mobility impedes performance once these micro-cantilevers or similar structures such as micro-bridges or membranes are immersed in liquids. Through the choice of polymer materials we enabled the free end of the cantilever to deflect a significantly long way up from its resting position, which makes it efficient and accurate in its response. We can probe for certain parameters, for example the viscosity and visco-elastic properties of blood, even at very small, sub micro-liter volumes.”

By 2004, Microvisk’s research team was confident about the strength of the technology and its potential for use by consumers in their own homes. The MEMS solution could be incorporated in a hand held device and the testing process was more robust than existing methods. The sample of blood required was tiny and accuracy was greatly improved. As chemicals were not needed to drive the test there was no shelf life issue and no requirement for strict storage controls before, during, and after testing.

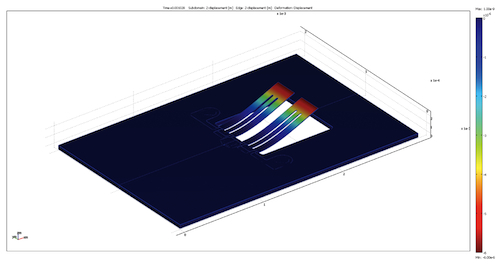

This is a COMSOL model showing deflection of the micro-cantilevers.

The very sophistication of the technology was also a challenge. “This solution is not so much about how the cantilever moves up and down,” commented Djakov. “It is more about a holistic approach to integration, packaging, and signal processing. The big questions in MEMS-based microchip design are how likely are the chips to perform and what are the set points? While the standard test interrogates material electronically, we also need to consider mechanical response, reproducibility, and reliability aspects such as cycling times and performance deterioration.”

This calls for an approach combining both mechanics and statics of beams systems with the thermal and electric properties of structural materials at hand. Complexity is further increased when a current is applied to the MEMS structures immersed in and interacting with fluids. A current changes electrostatic fields and alters mechanical structures and creates thermal effects. Djakov reports that when the research began there was no suitable modeling option and initially the team was unable to conduct multiple analyses of the MEMS. Then as multi-physics simulation software began to appear the company was restrained by its small size and limited financing. “We had to rely on past experience, basic know how and gut feeling. Determining the design was a long and tedious process involving laboratory experiments and real life tests.”

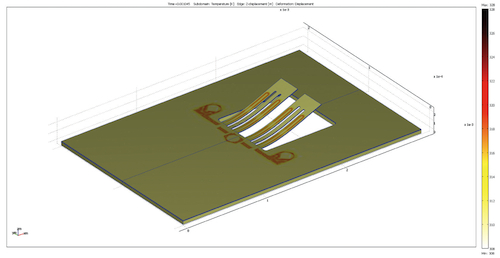

The COMSOL model shows an accurate thermal deflection.

In 2009 his team implemented COMSOL Multi-physics software. It helps Microvisk’s researchers see the microchips mechanically, thermally, and electro–statically. They can also analyze micro fluids and their properties and how these interface with the chips and moving cantilevers. “By linking all the physical properties of the design, COMSOL has sped up the whole process of iteration, reduced prototyping, and shortened development time. We no longer need to solve one problem, then another, and plot a graph after each step,” said Djakov.

Previously, data was collected from a number of prototyping variants of test strips then it had to be analyzed, understood, and verified. One iteration typically assessed 20 different design options plus the manufacturing and assembly implications of each. Through COMSOL modeling Microvisk was able to start picking out the most promising options and confirming simulation results with laboratory testing. After only 15 months the company had completed two major design iterations and a number of optimization refinements and Djakov estimates that it had saved four to five months of development time. “The software helps us look at much broader possibilities and decide to investigate two or three much further. This means that we achieve a better end product at the same time as cutting development time.” COMSOL software has facilitated design optimization and improved the way that the development team communicates with Microvisk’s investors. Models are easily presented to the board and progress is marked using color maps and video.

Jennifer Hand

freelance writer

New York, New York

COMSOL

www.comsol.com

::Design World