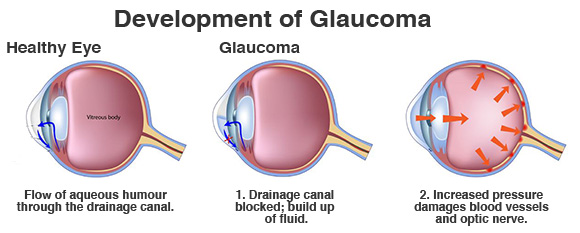

(Credit: Sarah Knows Eyes)

In a first of its kind study, Mount Sinai researchers are using optimal coherence tomography (OCT) angiography to look at the earliest stages of glaucoma and identify characteristic patterns of different forms of glaucoma based on their vascular patterns. The research could lead doctors to diagnose glaucoma cases earlier than ever before and potentially slow down the progression of vision loss.

OCT angiography is an advanced imaging system that captures the motion of red blood cells in blood vessels non-invasively, as opposed to traditional angiography, which uses dye injections. Using this technology, a team of scientists from the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai (NYEE) and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai have discovered that all glaucoma patients have fewer blood vessels, or less blood flow to the eyes compared to patients without glaucoma. The findings were published in the October 14 issue of IOVS.

Researchers analyzed 92 patients above the age of 50 between April and August 2015. They divided those patients into three groups based on their condition: primary open-angle glaucoma (high pressure); normal-tension glaucoma (low pressure); and no glaucoma. They used OCT angiography to look at the blood vessels in each patient, and found those with glaucoma had different patterns of defects in the blood flow in the most superficial layer of the retina depending on the type of glaucoma.

“This is the first time we have been able to identify certain characteristic patterns of blood flow that correspond to different types of glaucoma, which may allow us to identify certain forms of glaucoma in their early stages,” said lead investigator Richard Rosen, MD, Director, Retina Services, NYEE; Research Director, Ophthalmology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “The findings could lead to new therapeutic strategies to avoid progressive damage in glaucoma patients, and provide a new metric for monitoring early damage that eventually leads to vision loss.”

The team of researchers developed new software to analyze the images obtained with OCT angiography. This software was designed to map the perfused optic nerve capillaries in each eye to reveal the patterns of the blood vessels feeding the optic nerve fiber layer. They looked at patients with open-angle glaucoma and evaluated how their blood flow distribution differed from patients with normal-tension glaucoma. They then compared the patterns of the blood supply to the patterns of the optic nerve fiber layer loss due to glaucoma. In high-pressure glaucoma the pattern of blood flow loss closely matched the optic nerve fiber loss. In normal-tension glaucoma cases, the pattern of blood flow loss, while not significantly different from open-angle glaucoma, tended to be more diffuse.

“Normal-tension glaucoma is often picked up late because it’s not recognized if patients don’t have high pressure, causing them to lose nerve fiber and blood supply before diagnosis,” said James C. Tsai, MD, MBA, Chair, Department of Ophthalmology, Mount Sinai Health System; President, NYEE. “This study points to vascular factors contributing to normal-tension glaucoma and we can use this to help identify ways to detect the disease earlier, and possibly prevent vision loss.”

Further studies will help to refine identification of these characteristic patterns of blood flow that indicate normal-tension glaucoma. Future advancements in technology may also lead to OCT angiography becoming a standardized imaging modality for the diagnosis and management of glaucoma.

Rutgers New Jersey Medical School also contributed to this study.