University of California San Diego researchers have 3D-printed a functional blood vessel network that they believe could someday be used in artificial organs and regenerative medicines. The team’s work was published in Biomaterials.

University of California San Diego researchers have 3D-printed a functional blood vessel network that they believe could someday be used in artificial organs and regenerative medicines. The team’s work was published in Biomaterials.

Previous work in the field has yielded simple and costly structures, the researchers said, that are not capable of integrating with the body’s own vascular system.

“Almost all tissues and organs need blood vessels to survive and work properly. This is a big bottleneck in making organ transplants, which are in high demand but in short supply,” lead researcher Shaochen Chen said in prepared remarks. “3D bioprinting organs can help bridge this gap, and our lab has taken a big step toward that goal.”

Chen’s lab 3D-printed a blood vessel network that can integrate with the body’s own network and branch out into series of smaller vessels.

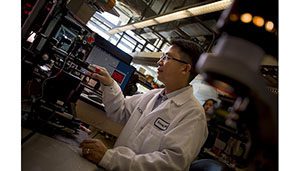

Using the team’s homemade printers, they manufactured complex 3D biomimetic microstructures – they’ve used this technology to create liver tissue and microscopic fish that can swim throughout the body, detecting and removing toxins.

The process begins by creating a 3D computer model of the biological structure. Then, the computer transfers 2D snapshots of the model to millions of tiny mirrors, which are digitally controlled to project the snapshots in patterns of UV light. The structure is printed quickly and continuously, 1 layer at time.

The finished product is a 3D solid polymer scaffold that encapsulates live cells and eventually becomes biological tissue. The process takes only a few seconds, according to the team.

“We can directly print detailed microvasculature structures in extremely high resolution. Other 3D printing technologies produce the equivalent of ‘pixelated’ structures in comparison and usually require sacrificial materials and additional steps to create the vessels,” lead researcher Wei Zhu said.

The researchers used their technology to print a structure containing endothelial cells, which line the blood vessels found in the human body. The entire structure is 4 mm by 5 mm and is as thick as a stack of 12 strands of human hair.

The team cultured many different structures for 1 day and then grafted the resulting tissues into the wounds of mice. After 2 weeks, the team noted that the implants had successfully merged with the host blood vessel network and that blood circulated normally.

However, the biomimetic blood vessels can’t yet transport nutrients or waste.

“We still have a lot of work to do to improve these materials. This is a promising step toward the future of tissue regeneration and repair,” Chen said.

[Want to stay more on top of MDO content? Subscribe to our weekly e-newsletter.]