UT Southwestern cardiologist Dr. Benjamin Levine will use NASA-honed technology to monitor swimmer Ben Lecomte as he plunges into the ocean off of a Tokyo beach this summer heading for San Francisco in his record-setting goal to become the first person to swim across the Pacific Ocean.

UT Southwestern cardiologist Dr. Benjamin Levine will use NASA-honed technology to monitor swimmer Ben Lecomte as he plunges into the ocean off of a Tokyo beach this summer heading for San Francisco in his record-setting goal to become the first person to swim across the Pacific Ocean.

Dr. Levine, a renowned sports cardiologist who holds the Distinguished Professorship in Exercise Sciences at UT Southwestern, is hoping to study the effects of the endurance swim on Mr. Lecomte’s heart.

“This is a continuation of our work and our interest in the effects of extreme conditions on the human body,” said Dr. Levine, Professor of Internal Medicine and Director of the Institute for Exercise and Environmental Medicine at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas, a partnership between UT Southwestern and Texas Health Resources that studies human physiology across the life span, especially physiology under extreme conditions, such as Mr. Lecomte’s epic swim.

One of the current controversies in cardiology is whether extreme athletic performance has a harmful effect on the heart. Despite the demands of Mr. Lecomte’s swim, Dr. Levine anticipates no negative effects on the swimmer’s heart.

Dr. Levine, who was part of NASA’s Specialized Center of Research and Training and the Human Research Facility (Space Station) Scientific Working Group, will use NASA-tested technology called remote guidance echocardiography to monitor changes to Mr. Lecomte’s heart during his swim. The technology is the same used to monitor astronauts on the International Space Station.

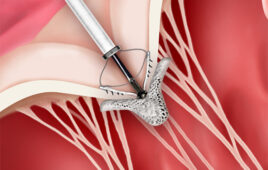

Echocardiography uses high-pitched sound waves that are bounced off the heart. Echoes of these ultrasonic waves are picked up by the machine and translated into a video image of the beating heart. Echocardiograms are usually performed by trained individuals called sonographers, but the remote guidance echocardiograph technology allows a sonographer to guide a modestly trained individual through the process in remote locations such as the International Space Station, a small village in Mozambique, or the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

Using this same technology, Dr. Levine and colleagues recently completed a seven-year study of the hearts of 13 astronauts who were living on the International Space Station. That study examined the impact of long-term microgravity on heart function.

“This is the ultimate in telemedicine. The astronauts spend a few hours training and practicing using echocardiography in the Space Station mock-up at Johnson Space Center. Some of them are really into it. I wouldn’t have thought it possible, but you get research-quality images,” said Dr. Levine, who holds the S. Finley Ewing Jr. Chair for Wellness and the Harry S. Moss Heart Chair for Cardiovascular Research at Texas Health Presbyterian Dallas.

Dr. Levine’s lab already began the research on Mr. Lecomte by taking baseline echoes of his heart.

“He’s lean and has a nice big heart that comes right up against the chest, so we took some beautiful two- and three-dimensional images, which will serve as a baseline for during and after his swim,” Dr. Levine said. “It looks fantastic. It’s large – appropriately so – and strong. It beats normally.”

Mr. Lecomte, a longtime Grand Prairie resident who recently moved to Round Rock, Texas, is a record-setting endurance athlete who was the first person to swim across the Atlantic Ocean. He is now looking to become the first to swim across the Pacific Ocean, with the goal of bringing attention to environmental issues.

“I’ve noticed changes in the water over my lifetime, more plastic, less and less sea life,” said Mr. Lecomte. “It is my duty as a father to try to do anything and everything I can to reduce the liability on the environment that I am going to pass on to my children.”

Mr. Lecomte, an architect who was born in France but is now a U.S. citizen, spent summers at a family home near Bordeaux, where his father introduced him to the glories of the outdoors. That is where he developed a passion for open-water swimming.

In 1998, Mr. Lecomte swam from Boston to France, becoming the first person to swim across the Atlantic Ocean. During the 73-day effort, he was repeatedly stung by jellyfish and followed for five days by a shark.

But that 3,395-mile feat pales in comparison with the effort to conquer the Pacific Ocean − a 5,500-mile journey that he expects to take 180 days. The 47-year-old has spent two years training and preparing for his swim – considering everything from the flow patterns of ocean currents to the boat that will accompany him on his journey.

“I have to find the right window as far as weather. That will be determined by the team on land. They will analyze satellite pictures showing the speed of the current, the size of the waves and all that. They will give us information on a daily basis, and the route will change every day based on that information.”

Mr. Lecomte swims at a speed of 2 to 2.5 knots in the wet suit and flippers he will be wearing, but ocean currents can flow at twice that speed, so it is crucial for him to be swimming with the currents. He plans to swim for approximately eight hours a day, using GPS technology to mark his starting and ending points.

He’ll battle 20-foot-high waves, dangerous marine life, and numbing boredom, Mr. Lecomte said. And he’s even looking forward to seeing sharks.

“The ocean is their place. I hope we are going to see sharks because it will be a great opportunity to tell the story about what we have done to them. Only 10 percent of the population of sharks now remains.”

For Mr. Lecomte, it’s a continuation of a lifetime of living on the edge.

“I don’t want to live a routine life. You have people who climb mountains. You have people who sail around the world. This is my passion,” he said. “People say to me, ‘Are you crazy?’ But for me, if you don’t live on the edge, then you are taking up too much space.”