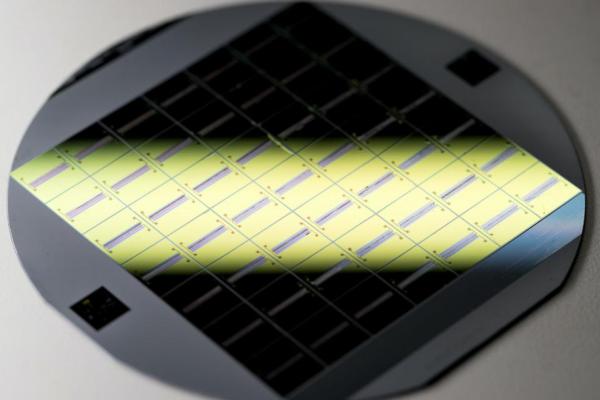

(Credit: Jaren Wilkey/BYU Photo)

BYU researchers have developed flexible glass for use in medical devices. The technology could inspire improved lab-on-a-chip devices.

“If you keep the movements to the nanoscale, glass can still snap back into shape,” electrical engineering professor Aaron Hawkins says in a news release. “We’ve created glass membranes that can move up and down and bend. They are the first building blocks of a whole new plumbing system that could move very small volumes of liquid around.”

Scientists say a flexible glass membrane will further shrink the scale at which lab-on-a-chip devices operate — from microscale to nanoscale. At the nanoscale, lab-on-a-chip membranes could trap and analyze proteins, viruses and DNA for diagnostic purposes.

Glass is the preferred material for device membranes because it’s sterile, strong and generally nonreactive.

“Glass is clean for sensitive types of samples, like blood samples,” says BYU doctoral student John Stout. “Working with this glass device will allow us to look at particles of any size and at any given range. It will also allow us to analyze the particles in the sample without modifying them.”

Scientists predict devices using flexible glass will require smaller sample sizes, thereby shrinking the amount of time it takes to run diagnostic tests.

“Instead of shipping a vial of blood to a lab and have it run through all those machines and steps, we are creating devices that can give you an answer on the spot,” Hawkins says.