A team of researchers with UT Southwestern Medical Center and the University of Chicago has developed a new imaging technique that may give scientists a relatively simple means to unravel which parts of proteins give them their function.

In their paper published in the journal Nature, the team describes their new method, which combines strong electric field pulse applications and time-resolved X-ray crystallography.

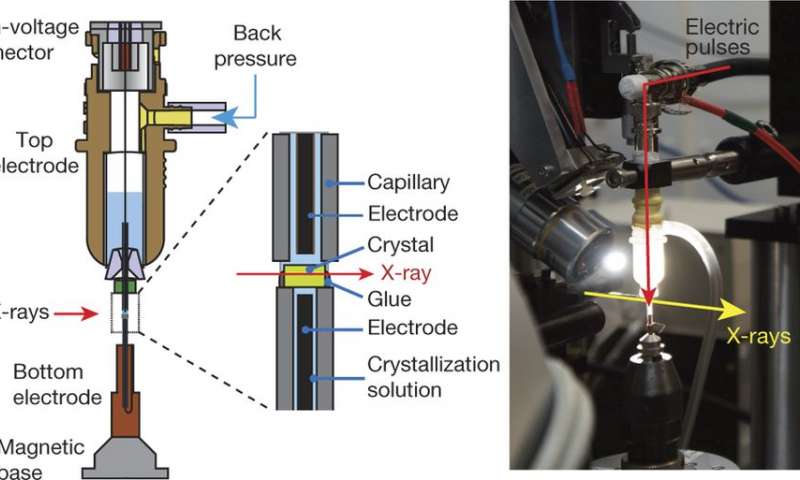

Left, The crystal is mounted on the bottom electrode and the high voltage is delivered from a top electrode through a liquid junction composed of crystallization solution. Controlled back pressure on a reservoir of solution in the top electrode keeps the crystal continuously hydrated. Right, A view of the assembled experimental apparatus. (Credit: (c) Nature (2016). DOI: 10.1038/nature20571/ Phys.org)

As part of the never-ending search to fully understand how living entities work, scientists have developed a multitude of imaging techniques—one of these, X-ray crystallography, has been used to study molecules from living creatures, and more specifically, proteins. Its use has led to many breakthroughs in biomedical science, but it suffers from one serious problem—it does not allow researchers to see how a protein actually does its job; instead, it simply offers structural imagery.

The researchers note that there are other technologies that offer some assistance in studying the workings of proteins, some of which can even track motion, but most work only under certain conditions or with certain proteins. In this new effort, the researchers report on how they combined two technologies to allow future researchers to capture imagery of virtually any kind of protein doing its work.

The new technique involves taking X-ray images of protein reactions during application of an electric field—protein processes, they note, are generally controlled by electromagnetic forces. Protein crystals are placed between glass capillaries containing a wire that applies an electric force across the crystals as they are subjected to X-ray pulses. The results can be seen in diffraction patterns recorded over several intervals—just prior to an electric pulse, and then again at 50, 100 and 200 nanoseconds.

The team notes that the technique should work for studying virtually any protein, potentially offering a new tool to assist in designing new proteins or drugs.

The group reports that they used the technique to study the human ubiquitin ligase protein which is part of the PDZ domain and found new information regarding how it actually works.