While simulation platforms have been used to train surgeons before they enter an actual operating room (OR), few studies have evaluated how well trainees transfer those skills from the simulator to the OR. Now, a study led by Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute that used noninvasive brain imaging to evaluate brain activity has found that simulator-trained medical students successfully transferred those skills to operating on cadavers and were faster than peers who had no simulator training.

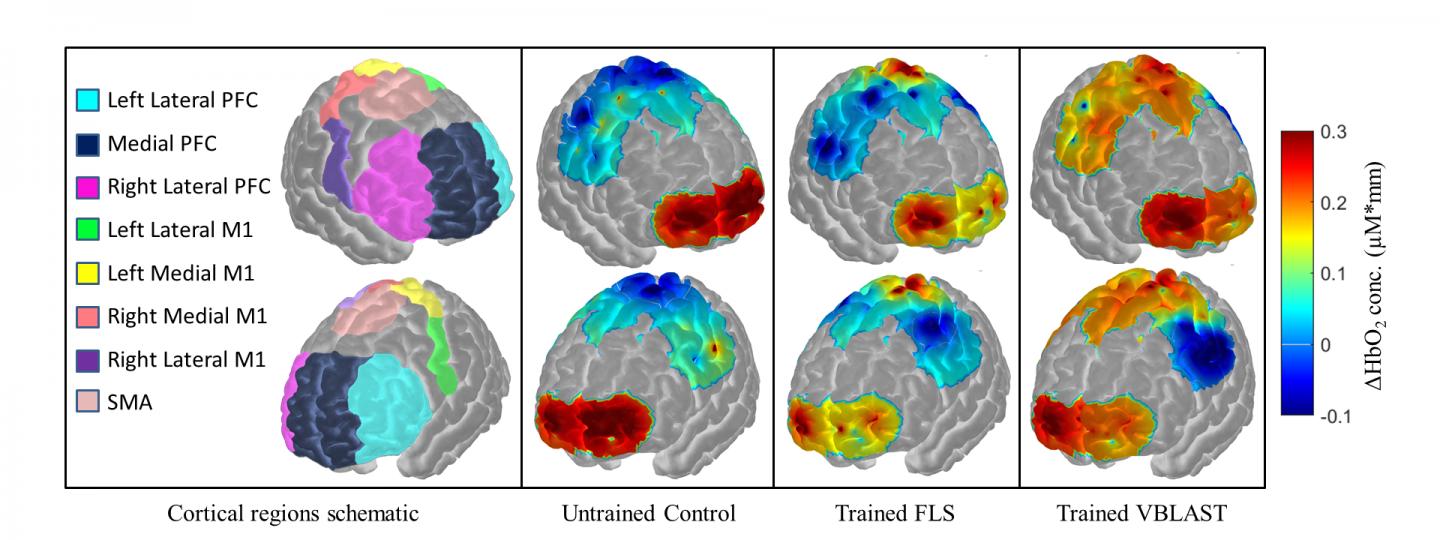

In this rendering, spatial maps of functional activation with respect to varying degrees of training levels during the ex-vivo transfer task. Spatial maps cover specific regions including the prefrontal cortex, primary motor cortex, and supplementary motor area for all subjects. (Credit: Arun Nemani)

The study, led by Suvranu De, the J. Erik Jonsson ’22 Distinguished Professor of Engineering and head of the Department of Mechanical, Aerospace, and Nuclear Engineering; and Xavier Intes, professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering and director of the Functional & Molecular Optical Imaging Laboratory; along with Arun Nemani, M.S., a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and the first author on the study, evaluated the surgical proficiency of 19 medical students, six of whom practiced cutting tasks on a physical simulator, eight of whom practiced on a virtual simulator, and five of whom had no practice. Last month, study results were presented at the American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress 2017.

“We plan on using these study findings to create robust machine learning-based models that can accurately classify trainees into successfully and unsuccessfully trained candidates using functional brain activation,” said Nemani.

The medical students who practiced on the physical simulator completed the task in an average of 7.9 minutes with a deviation (±) of 3.3 minutes. Those who used the virtual stimulator did the task in 13.05 minutes (±2.6 minutes) vs. an average of 15.5 minutes (±5.6 minutes) for the group that had no practice (p<0.05).

Brain imaging measured activity in the primary motor cortex, located in the frontal lobe. The researchers found that the simulator groups had significantly higher cortical activity than the group that had no training.

“By showing that trained subjects have increased activity in the primary motor cortex when performing surgical tasks when compared to untrained subjects, our noninvasive brain imaging approach can accurately determine surgical motor skill transfer from simulation to ex-vivo environments,” Nemani said.

“This is a significant leap in the use of noninvasive brain imaging technology to quantify human motor skills and represents a paradigm shift in which surgeons and other medical professionals may be certified and credentialed one day,” said Suvranu De, who also serves as Nemani’s faculty adviser. The research builds on the long history of the Center for Modeling, Simulation and Imaging in Medicine (CeMSIM) in advancing patient care through cutting-edge research and innovation.”

“These results demonstrate that optical neuroimaging provides quantitative and standardized metrics for assessing surgical skills acquisition and expertise,” said Intes. “Hence, optical neuroimaging is uniquely positioned to play a central role in developing tailored surgical training programs for optimal skill acquisition and retention assessment, as well as for facilitating bimanual skill-based professional certifications.”

The researchers believe this study is the first one to show clear functional changes that transfer into surgical skill in individuals who had simulator training. “This work addresses underlying neurological responses to increased motor skill training that is often missing in current surgical simulator literature,” Nemani said.

According to the researchers of this study, objectively determining if a surgeon in training has achieved the motor skills necessary to perform surgery before actually doing surgery in the OR is crucial. “Brain function-based metrics, which do not depend on subjective or inaccurate task performance metrics, may bring significantly more objectivity in surgical skill transfer assessment,” Nemani said.

This study underscores the value of simulation and pre-planning operations by objectively showing functional changes in brain activity as surgeons learn new skills. “Now, we can quantify changes in brain activation as trainees master surgical tasks on a simulator and transfer to more clinically relevant environments,” Nemani said.

“This work highlights the power and impact of multidisciplinary collaboration at the interface of engineering, biomedical sciences, and computation,” said Shekhar Garde, dean of the School of Engineering at Rensselaer. “I sense that these results on connecting and measuring brain activity to fine motor skills are only the beginning, with many more diverse applications to come that will improve health care, human health and fitness, and quality of life for the global population.”

The multidisciplinary, collaborative team comprised of researchers from Rensselaer, Harvard University, and the University at Buffalo is enabled by the vision of The New Polytechnic, an emerging paradigm for higher education which recognizes that global challenges and opportunities are so great they cannot be adequately addressed by even the most talented person working alone. Rensselaer serves as a crossroads for collaboration — working with partners across disciplines, sectors, and geographic regions — to address complex global challenges, using the most advanced tools and technologies, many of which are developed at Rensselaer. Research at Rensselaer addresses some of the world’s most pressing technological challenges — from energy security and sustainable development to biotechnology and human health. The New Polytechnic is transformative in the global impact of research, in its innovative pedagogy, and in the lives of students at Rensselaer.

Future research will expand to include other cortical areas associated with motor skill learning, such as the prefrontal cortex and supplementary motor areas, according to Nemani. “These next steps will help provide a comprehensive map on functional changes within the brain as surgical motor skill increases,” he concluded.