“It’s an illusion to think that everyone is interested in tracking their health.”

Which lessons were learned from the large-scale survey that imec* carried out on the topic of health apps and wearables?

The beginning of a changed society

This was the second time that An Jacobs and her colleagues from the imec.livinglabs team organized a large-scale online survey on health apps and wearables. As we’re at the beginning of this new technological transformation, it is interesting to track this evolution, also from a sociologist’s point of view. It’s a societal change that can provide a lot of fascinating insights. By repeating the questionnaire each year, you can gather an interesting dataset that allows you to track the evolution year by year. This is valuable information, not just for sociologists, but also for the companies and researchers that develop these health apps and wearables.

For instance, the findings of this survey explain why people use these tools and – equally important – why they stop using them. This way companies can address the needs and frustrations of their clients and motivate more people to start tracking their health.

This year’s participant group consisted of 1297 people (49% men, 51% women). All participants were already active online and are representative for the Flemish population with regards to age, level of education and socioeconomic status.

Do my jeans still fit?

The questionnaire indicated that 96% of participants keep track of their health in one way or another. This can include data on daily activity levels, sleeping pattern, weight, or heartrate. Surprisingly, only 32% of these participants use health apps or wearables to keep track of this information.

Almost half of the participant group indicated that they just kept track of health information ‘in their heads’. Most of them are aware of their average weight or blood pressure and know whether they are good or light sleepers, but not everyone seems to feel the need to keep track of this accurately. A couple of years ago the American PEW Institute conducted a similar research and noted that many people monitor their weight with the simple question: “Do my jeans still fit?”. So to be effective, technology for health monitoring should be just as intuitive. Most people are not willing to open an app every day or to enter data manually.

We are all interested in our health, but keep track of health data in different ways.

Only for sporty types?!

Google Fit, Weightwatchers, Runkeeper, etc. These are just a few examples of all the health apps out there. Jacob’s personal favorite is Headspace, a beautiful and simple meditation app.

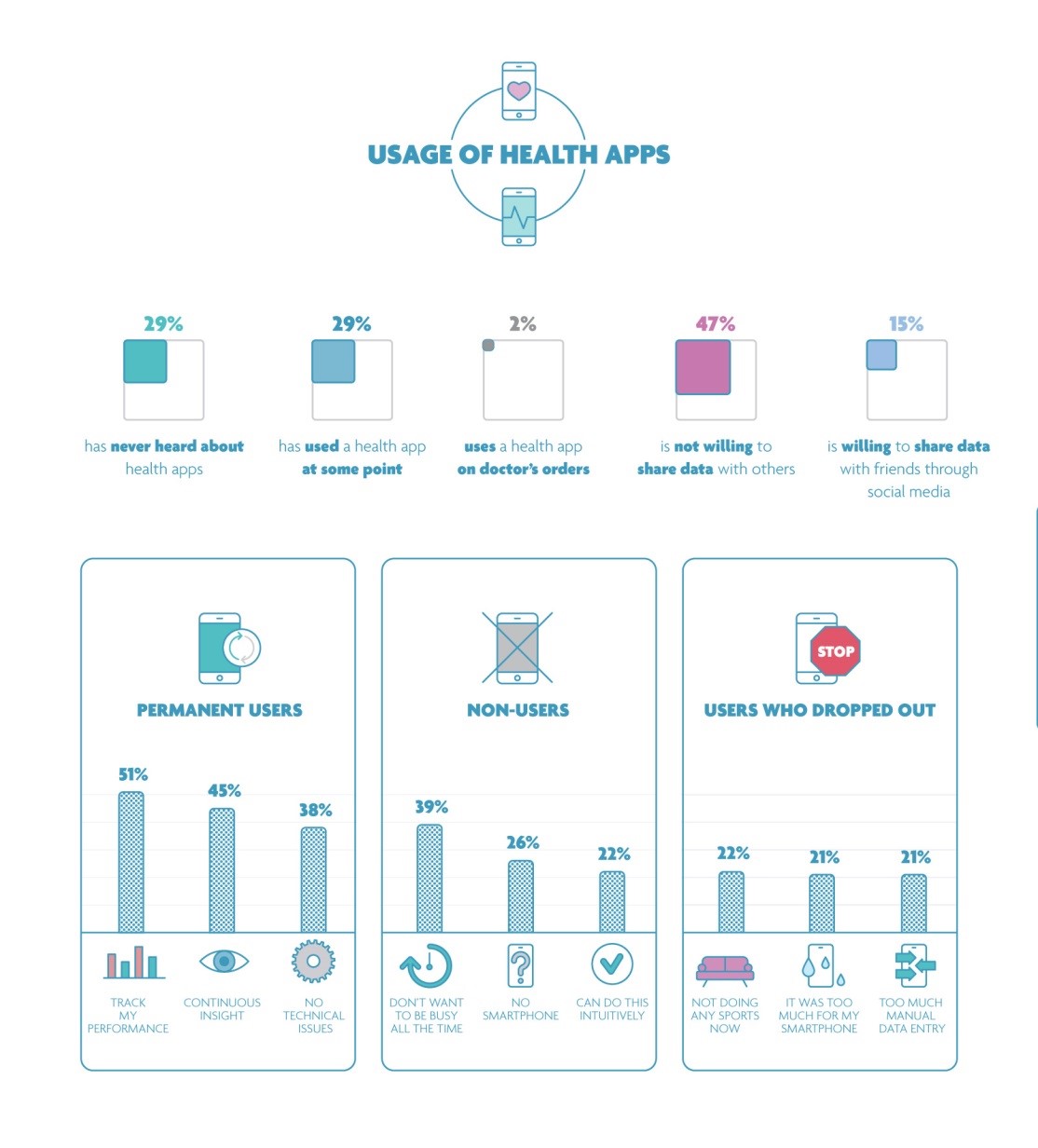

About one third of those surveyed had at some point downloaded and opened a health app, mainly to track sports activities. Those who keep using such apps (79%) mainly do this because the continuous measurements provide insight into their fitness levels and habits.

But many drop out (21 percent ), mainly due to technical issues with the app, the high battery use, the fact that it requires too much effort (too much data requires manual entry), and privacy concerns about sharing personal data. People who have never used a health app often indicate that it’s not for them because they don’t like sports. So clearly there is still a strong misconception that these apps are only for the more sports-minded people among us. Nevertheless, the apps are actually especially useful for less active people.

The survey’s results on the use of health apps. Credit: IMEC

The survey’s results on the use of health apps.

And then there are wearables like the Fitbit, Apple Watch, Garmin Vivomove, etc. Jacobs owns a couple of these wearables and likes to test different kinds. Today she’s wearing one from Withings (recently taken over by Nokia). It looks like a classic watch, but also measures your heartrate and sleeping pattern.

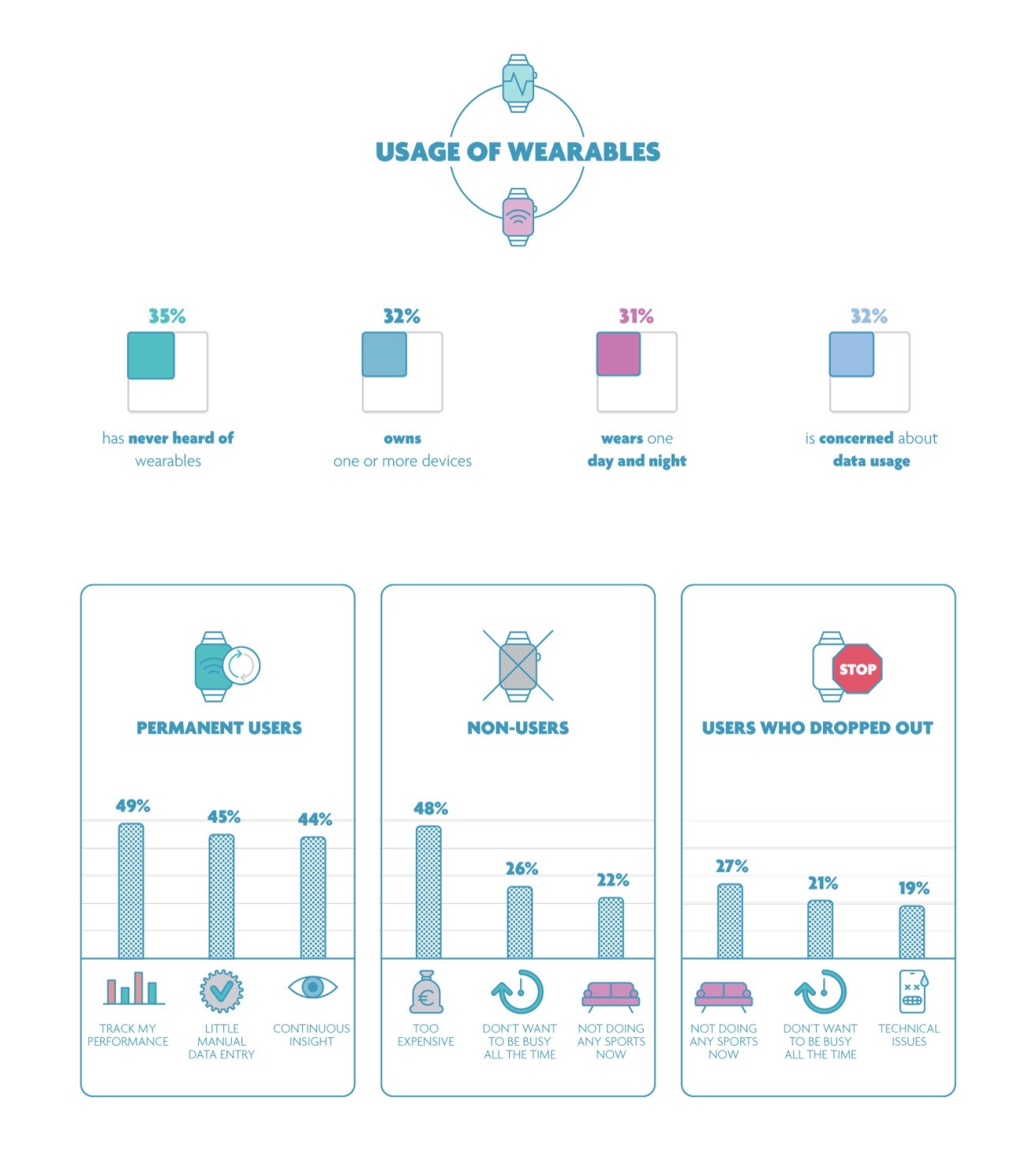

The survey indicated that one third of participants owns at least one wearable. The others believe that wearables are too expensive or only meant for more active, sporty people.

The survey’s results on the use of health wearables. Credit: IMEC

Three health tracker profiles

Thirty-two percent of the participants use a health tracker and/or wearable. But what kind of people are they? Are they all superathletes? Through a cluster analysis, the researchers were able to define three different user profiles. The first group is ‘the casual curious tracker’. They (m/f) work fulltime and are not really into sports. They buy the app or wearable out of curiosity, but the device doesn’t really motivate them to choose a healthier lifestyle. The second type of user is the ‘concerned motivated tracker’. These people (m/f) also work fulltime and tend to have a sedentary profession. They believe it’s interesting to track data digitally, but at the same time they are concerned about privacy. The third group, ‘the public omnivore tracker’, is sporty and likes to use different kinds of wearables and apps to track their performance. This group also likes to share their data through social media.

The tree kinds of trackers: casual, concerned and omnivore

Not everyone is on board

But let’s be clear: there are also many people who do not use health apps or wearables or that stop using them rather quickly. The survey suggests several reasons for this: it’s expensive, there are too many technical problems, you need to enter too much data manually, the battery of your smartphone or wearable drains easily, it’s inconvenient to carry your smartphone or wearable around all the time, etc.

If you set goals for yourself, you might fail and many people fear this disappointment. And some people are simply too busy to set goals for themselves, or they just want to have fun without having to worry about meeting goals. The apps and wearables that are on the market today were only developed for a specific target group of people who are able and willing to set goals for themselves. In other words, there’s clearly an opportunity to develop tools for a target group that does not feel comfortable with this.

As in the previous survey, almost half of the health app users (47%) preferred not to share their data.

The ‘concerned motivated tracker’ is especially concerned about the information health apps and wearables collect and how these can invade his/her privacy. That’s why this type of user is less prepared to share their data with third parties (55%) in comparison to the public omnivore type (39%). The concerned motivated tracker is also unsure about whether third parties (like doctors) will take the data collected by these devices seriously.

Recommendations for developers of apps and wearables

The results of this survey and the conclusions drawn by sociologists like An Jacobs provide valuable information for the development of apps and wearables. Some of these recommendations are straightforward: optimizing battery life, increasing user-friendliness, and lowering the price. But other changes need to be made as well.

One of the problems with most apps and wearables is that they are designed to make you feel guilty.

Nothing is more frustrating than a tool that pushes you to get up and move while you’re ill and in bed. People want apps that are more ‘forgiving’ and/or can take into account a broader context so they understand what else is going on.

This last aspect is connected to the personalization of apps and wearables.

Is it a good idea to develop tools that gradually get to know their owner better so they can serve him/her more efficiently?

Jacobs indicates that we should be careful with this. Some people will experience this as somewhat ‘creepy’ or confronting. It’s better to leave this up to the user and let him/her determine the level of personalization. If personalization makes the app or wearable more effective, then users will accept it. Imec’s ‘imec.iChange’ research program focuses on this kind of personalization: by using smart algorithms and contextual data, wearables and health apps can become more efficient and user-friendly.

The survey also indicates that people are not willing to carry around their smartphone or wearable the whole time. Hence, it’s a good idea to integrate sensors into smart textile or jewels. A heartrate meter integrated into a pretty shirt or bra, or a pedometer that’s part of a beautiful ring will be able to convince a much wider target group. Some companies are already aware of this trend. For instance, the fitbit activity tracker is available in different, more aesthetic designs, branding it as a classy bracelet rather than a performance tracking tool that’s only meant for the more sporty people amongst us.

But even then, companies still need to take into account that people will not track their movement and activity continuously. At night, for instance, most people put aside their wearable.

Consequently, it’s important to develop algorithms that can still draw the right conclusions despite missing data. One option would be to fill the gaps by combining data from different sources.

Another common problem with wearables is that they need to be charged. Not everyone remembers to plug in their wearable or laptop in time. This can easily be improved. For instance, we already have coffee tables that allow you to charge your phone wirelessly – through a magnetic field. Could we do the same with wearables? Jacobs refers to the imec.icon WONDER project in retirement homes. In this project they want to let the residents meet with a robot to assist them. The robot must be able to identify each individual resident and the researchers want to do this by integrating a tag in the shoes of the residents. As most people tend to have a fixed place to put their shoes, the shoes can be charged by simply placing them on a special shoe mat. Using and charging wearables should become just as intuitive as this solution.

Doctor’s orders

The main problem is that doctors do not know which apps/wearables to trust. There are so many products out there and unless they should be certified before being launched, it’s hard for doctors to know which products are reliable.

In England, the National Health Service provides reliable health apps with a label indicating their trustworthiness, and in the US private hospitals and health insurances are starting to promote the wearables that they believe in. In Flanders, the government is also working on something similar, but at the moment there is no label or certification yet. Deciding which apps to trust, is not an easy feat. They can’t be certified in the same way as medical equipment, because they are updated continuously and can’t go through the entire procedure again each time. Jacobs also points out that – even if wearables and apps are prescribed by doctors – that doesn’t mean everyone will use them. Just think of the number of people who forget to take their medication. To address this issue, health apps should consider why people “forget” and provide incentives to motivate them.

The future

It’s always hard to predict how technology usage will evolve over the years. Jacobs hopes that within 10 years we’ll have certified health apps, wearables, clothing, jewels, etc. that will be part of doctors’ basic instruments. Using and interpreting the data that is collected in this way should also become part of doctors’ medical training. And of course, we need to be careful and make sure that users remain in control of their data and the artificial intelligence used in these products.

With the imec.iChange program imec is paving the way for the medical future of wearables. In this research program imec brings together companies and hospitals to create a virtual personal health coach, building primarily on mobile sensors and data science. This coach could be used to motivate people to live a more active or healthy lifestyle, to control stress, or to quit smoking. In this way, imec aims to contribute to better preventive healthcare, thus reducing the development of chronic diseases.

An Jacobs is a sociologist at imec-SMIT-VUB and Lynn Coorevits is a psychologist at imec-mict-UGent