In remote, rural corners of Malawi, hospitals are often faced with life-and-death decisions. Women in need of emergency caesarean sections, older people with hernias, and children with appendicitis need surgery. But should they be rushed to the operating theatre or transferred to specialists in city hospitals?

The answer depends on the patient’s condition, the distance to the city, and the facilities available at the local hospital. Surgical skill, clinical experience and confidence are also critical factors.

Until recently, smaller hospitals, typically with around 200 beds and just two or three qualified general practitioners (GPs), usually recent graduates with a couple of years’ experience, often felt it safer to transfer patients for surgery.

A handful of clinical officers – a grade of health professional without a medical degree – is responsible for transfers and sometimes provide routine surgical procedures in rural clinics. While vital to local health systems, their surgical experience and clinical judgment may be limited and many feel professionally isolated from teaching hospitals.

“Clinical officers are not surgeons per se and they are not well connected to surgical specialists. But with supervision, there is a lot they can do,” said Gerald Mwapasa, a researcher at the College of Medicine, University of Malawi.

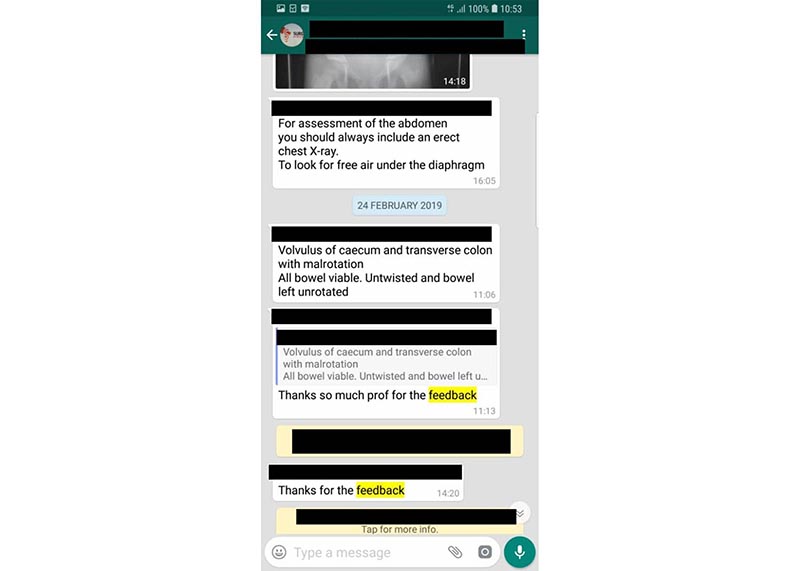

Mwapasa is the moderator of an invite-only WhatsApp group that allows health workers to ask specialists for advice before – or sometimes during – surgical operations.

“Before the WhatsApp groups, doctors in regional hospital felt specialists were difficult to reach, now they are approachable,” he said.

The group arose as part of a project called SURG-Africa, of which Mwapasa is the Malawi project coordinator. The aim is to expand access to safe surgery in sub-Saharan Africa through training, supervision and the increased use of the World Health Organization’s surgical safety checklist.

As part of the project, researchers in Malawi are working to strengthen district-level surgical teams and the links between rural and urban referral hospitals. They considered developing an app to connect health professionals and enable them to share images and videos, but they realised that WhatsApp was a solution right under their nose.

Vital support

The group has become a vital support for rural hospitals faced with clinical dilemmas.

“It gives clinical officers confidence when making decisions,” Mwapasa said. “They can get advice on performing hernia surgery, or how best to prepare a patient for transfer rather than attempt a procedure that the hospital might not have the facilities to manage.”

In 2018, around 200 cases were discussed by the group, all of which would have previously been referred to urban hospitals. Thanks to the advice given, less than two-thirds of these patients had to be transferred.

Martin Malunga, a clinical officer who does surgery at Mulanje District Hospital in southern Malawi, says the group is a valuable educational tool.

“If one district (hospital) posts a case and a consultant responds, then all of us learn,” he said. “The WhatsApp group has improved management by providing advice on how to operate or what to do before to referring a patient to a specialist.”

This view is echoed by Dr. Tiyamike Kapalamula, a paediatric surgeon at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital in the financial capital Blantyre who offers advice via WhatsApp.

“The cases that are recommended for referral arrive here in better shape because the basic investigations, resuscitation and preparation work is already done at the district level,” she said.

In 2018, 65% of the cases submitted to the WhatsApp group received a recommendation from a specialist within an hour. Credit: SURG-Africa

Strict guidelines apply on what content can be posted. To safeguard privacy, no patient names, faces or identifiable images are shared. Around 40 questions per week are shared, usually by clinicians at one of the nine participating district hospitals. Initially it was a challenge to brief people on the group’s purpose, says Mwapasa, but it’s now easier to manage.

Since starting in March 2018, more than 160 healthcare workers have signed up. Another group has started focusing on obstetrics and gynaecology.

Teams of specialists also visit remote areas to provide training and mentorship, according to SURG-Africa project leader Dr. Jakub Gajewski, who is at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland. Before, rural clinicians had limited contact with specialists between visits, but with the group they now stay in touch.

“This helps reduce the sense of isolation for doctors working far from teaching hospitals,” he said.

Whole system

Dr. Gajewski says the project is helping to unlock the potential of health workers and, by cutting out unnecessary referrals, specialists can focus on complex patient cases they are trained for. “The whole system benefits from this,” he said.

With representatives from the Ministry of Health, the Medical Council and the blood transfusion service in the group, members have been able to flag supply shortages and swiftly receive replacements for tools such as surgical lamps.

The initiative has garnered interest in Zambia, Tanzania, and Rwanda where surgeons are keen to explore how a messaging app could bridge the gap between surgical communities and improve the lives of patients and doctors.

But for health services in sub-Saharan Africa, one of the biggest challenges remains the limited availability of health professionals. Too few are trained and many leave Africa to develop their skills. Most African nations have fewer than one doctor per 1,000 people – the EU average is more than 3.5 per 1,000.

The implications of this can be devastating. Take maternity care, for example. While Africa is the continent with the highest birth rate – Malawi’s fertility rate is 5 births per woman, for example—maternal mortality rates in sub-Saharan Africa are significantly higher than other regions of the world at 920 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births.

“Without enough health professionals, either the quality or accessibility of care is dramatically affected,” said Professor Paul Cunningham of International Information Management Corporation (IIMC), an Irish tech company coordinating mHealth4Afrika, a project focused on improving primary healthcare in Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi and South Africa.

Technology is critical for strengthening the delivery and and scaling access to primary healthcare, he says.

For local health decision-makers, a key challenge is collecting accurate data from clinics so that they can predict demand and therefore plan future investments. For patients, better use of resources would reduce the long waiting times for high-demand health needs.

Primary care

While there has been a move towards electronic patient records in urban hospitals in many African countries, Prof. Cunningham says paper-based records remain the default mode for primary care data collection.

Working with partners in Africa, Norway and Turkey, IIMC has co-designed a patient-centric health IT system used by health ministries and district offices, clinic managers and nurses in the four African countries. He described it as a ‘cradle to grave’ approach to patient care, tracking health information throughout their lives – and building confidence in healthcare IT in the process.

This electronic system can capture and integrate personal health records as well as compare medical data over time. The platform can save time during consultations and gives health professionals up-to-date patient information to help guide decisions.

By automating the counting of key health indicator data, such as births, deaths, vaccination rates and illnesses, staff can instead focus on clinical tasks, while health ministries have access to more accurate data to inform policy and service planning.

The platform now incorporates key medical programmes including maternal health, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS and cervical cancer screening. Support is currently being added for diabetes, malaria and hypertension – all major challenges in the region.