All those charged with keeping a healthcare facility’s medical devices properly cleaned and ready to go are familiar with the acronym IFU, which stands for “instructions for use.” But when Steven Kovach surveys the field, he thinks a modification of the terminology is in order.

“I believe the F in IFU stands for ‘forgotten,’” says Kovach.

The main problem with this widespread forgetfulness is that it severely compromises patient care and safety. And that puts hospitals and other healthcare facilities in a dangerous place.

Kovach cites the 2009 case of John Harrison, a patient at Houston’s Methodist Hospital who suffered through debilitating complications and invasive follow-up procedures after shoulder surgery. Harrison figured he hadn’t been vigilant enough in looking after the wound in his recovery process, at least until he discovered several other patients were similarly struck with infections.

A subsequent investigation by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) traced the problem to arthroscopic shavers. The U.S Food and Drug Administration (FDA) then become aware of events in which tissue had remained within certain arthroscopic shavers, even after the cleaning process was believed to have been completed according to the manufacturer’s instructions at that time.

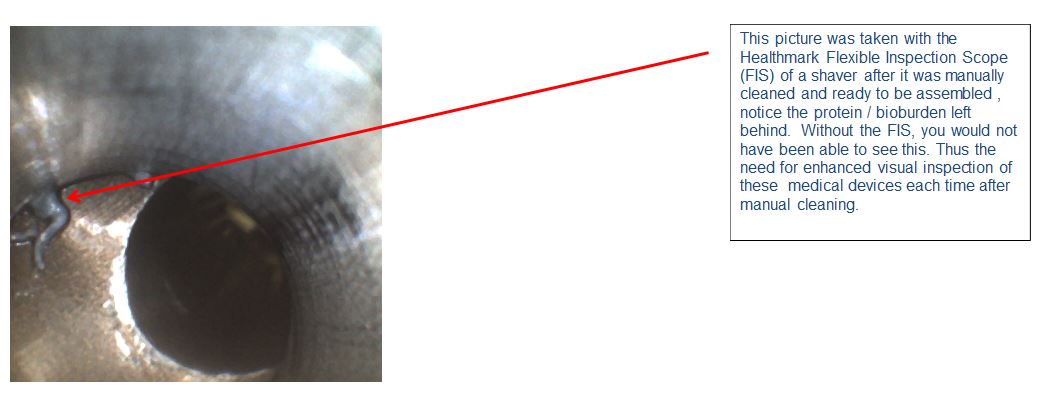

Reports submitted to the FDA suggested that the tissue retained was not evident to the naked eye. Multiple manufacturers of these devices informed their customers of the situation and reiterated the importance of dictated cleaning procedures, including use of proper brushes, correct cleaning times, and the employment of a lighted inspection scope to look inside the trouble areas.

The Healthmark Flexible Inspection Scope is used to aid in visual inspections of medical devices. (Image credit: Heathmark)

These statements were backed by a 2011 FDA summit presentation delivered by medical device company Smith & Nephew. According to Kovach, the manufacturer audited 12 facilities that were using shavers, specifically observing the reprocessing of 78 devices. They found that none of the facilities complied with all of the cleaning instructions found in the IFU, and 95 percent of devices had visible residue on internal surfaces.

For Kovach, these incidents should have been the tipping point that prompted hospitals to examine and then improve their own practices.

“If risk management really looked into what was going on they might see something has to be done. For example, a shaver can’t be turned around in 3 or 4 minutes when the IFU says it should take at least 10 minutes and you need 3 specific brushes,” says Kovach. “I think they would all of a sudden say, ‘Why have we taken on the risk of doing it differently than what a company says?’”

The major challenge for most sterilization professionals is the constant time crunch. When the overwhelming concern is to speed turnaround times to get the next patient wheeled through the OR doors, it becomes far too tempting to take shortcuts.

While many healthcare facilities are dramatically improving their supply chain management, the scope of that work often does not take into account all the details pertinent to the inventory.

“They say they know how many instruments they have, but do they know how long it takes to reprocess according to the IFU and turn them around?” Kovach asks. “I’m not sure everyone grasps and understands that time factor.”

Without the knowledge about cleaning and sterilization steps built into the process, healthcare facilities might have an inadequate number of devices to handle expected workloads, compounding the pressure to reprocess equipment more quickly than is reasonable according to the steps in the IFU. As technological advances led to ever more complex instruments, reprocessing times aren’t likely to drop any time soon.

(Image credit: Steven Kovach)

Besides an expectation that the IFU is always followed, Kovach believes there needs to be widespread institutional commitments to continuing professional education.

“Things change — we’re in a dynamic process,” he notes. ” And you want to keep everyone’s skill level to the highest level you can. Quality checks are very important.”

Kovach also suggests the time has arrived for the healthcare industry as a whole to factor considerations around reprocessing times into a wide array of decision-making processes. That should start at the very beginning, when device manufacturers are designing the equipment. The longstanding commitment to taking the end user into account should broaden from physicians who use the devices in procedures to those who clean and sterilize.

“The more people sit down and try to figure it out, the better,” says Kovach. “Get the device manufacturers together with the users — the sterile processing personnel as well as the physicians — so when somebody designs the device, they’re thinking, ‘How can it be cleaned and sterilized?’”

It’s obviously important to always follow the IFU. But the call to make those instructions more manageable is no less compelling.

(Photo credit for main image: Wyoming Medical Center)