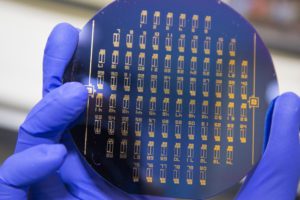

A close up of the liquid biopsy chip developed in WPI’s Small Systems Laboratory. Etched into the chip are 76 test units. [Photo courtesy Worcester Polytechnic Institute]

The device uses antibodies that have attached to carbon nanotubes at the bottom of a well. The cancer cells bind to antibodies based on surface markers that are at the bottom of the well. The chip also traps exosomes that are made by cancer cells.

Metastatic cancer cells are cancer cells that have moved from the original tumor site through the bloodstream to other parts of the body. Metastatic cancer cells all have the potential to grow into a tumor, but most of the time, spreading cancer cells die before they can go through all the steps to allow a tumor to grow.

Cancer cells can be hard to control once it spreads. Most metastatic cancer cannot be cured with current treatments, but the types that can be cured are only treated to stop of slow the growth of the cancer cells, according to the National Cancer Institute.

The chip has the potential to detect metastasis cancer cells before they have a chance to form tumors, increasing a patient’s chance for recovery.

The WPI device has an array of tiny elements that are about 3mm across and have a well at the bottom where the antibodies attach to certain types of cancer cells, based on genetic markers in the blood. It only needs a drop of blood to be able to sense cancer cells. Most other devices use microfluidics to capture cancer cells.

Researchers were able to fill 170 wells with 0.3 fluid ounces of blood. They captured between one and 1000 cells per well with an efficiency between 62 and 100 percent.

“The focus on capturing circulating tumor cells is quite new,” said Balaji Panchapakesan, associate professor of mechanical engineering at WPI and director of the Small Systems Laboratory. “It is a very difficult challenge, not unlike looking for a needle in a haystack. There are billions of red blood cells, tens of thousands of white blood cells, and, perhaps, only a small number of tumor cells floating among them. We’ve shown how those cells can be captured with high precision.”

So far, the tests of the chip have been mainly focused on breast cancer, but Panchapakesan hopes that the device could be used for a wide range of tumor types and used for more than just cancer patients and in routine cancer screenings.

“Imagine going to the doctor for your yearly physical,” Panchapakesan said. “You have blood drawn and that one blood sample can be tested for a comprehensive array of cancer cell markers. Cancers would be caught at their earliest stage and other stages of development, and doctors would have the necessary protein or genetic information from these captured cells to customize your treatment based on the specific markers for your cancer. This would really be a way to put your health in your own hands.”

The study was published in the IOP Science journal online.

[Want to stay more on top of MDO content? Subscribe to our weekly e-newsletter.]