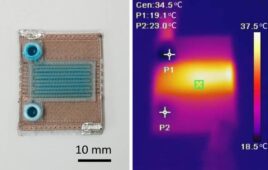

Using fugitive ink, a convoluted hollow channel is fabricated to mimic the winding shape of natural proximal tubules found inside a human kidney’s nephrons. [Photo credit: Wyss Institute at Harvard University.]

Harvard University engineering professor Jennifer A. Lewis and her team, in collaboration with Roche scientist Annie Moisan, have constructed a functional 3D renal architecture that has living human epithelial cells. These cells are what line the kidneys.

3D printed organs can be used as a solution for organ donor shortages, according to a 2014 Pharmacy and Therapeutics article relayed by the National Institutes of Health. If cells are taken from an organ transplant patient’s own body and used to build a replacement organ, the amount of time it takes to find a donor with a tissue match can be reduced. (The cost of organ transplant surgery and any follow-up procedures was more than $300 billion in 2012.)

Other pioneers in the field include Anthony Atala, MD, and the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, which announced the printing a human ear sophisticated enough that it was transplant-worthy. Meanwhile, researchers at Trinity College Dublin in Ireland have made strides 3D printing complex bone material.

To create the renal architecture, Lewis and her team cast an extracellular matrix as a base layer using a mold. Then they printed a temporary ink into a tubular shape to simulate the structure of actual renal tubules. They then cast the resulting product in a final extracellular matrix and the temporary ink was removed.

They perfused the inlet and outlet on the ends of the tubule with cell growth medium and human proximal tubule cells that cling to the tubule lining, creating a cell barrier between the inside and outside of the tubule.

Nutrients in the tubule kept the cells alive and functional so that they could continue to grow and the 3D printed renal architecture to function as a real renal system.

[Want to stay more on top of MDO content? Subscribe to our weekly e-newsletter.]