Staphylococcus aureus [Image from Wikipedia is courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]

“We were exploring a different approach for creating antimicrobial materials when we observed some interesting behavior from this polymer and decided to explore its potential in greater depth,” said Rich Spontak, an NC State chemical and biomolecular engineering professor and co-corresponding author of a paper on the work.

“What we found is extremely promising as an alternate weapon to existing materials-related approaches in the fight against drug-resistant pathogens,” Spontak said in an Aug. 2 news release. “This could be particularly useful in clinical settings – such as hospitals or doctor’s offices – as well as senior-living facilities, where pathogen transmission can have dire consequences.”

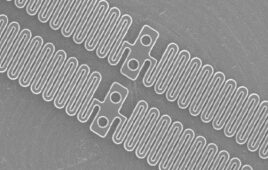

The polymer’s unique molecular architecture attracts water to a sequence of repeat units that are chemically modified (or functionalized) with sulfonic acid groups.

“When microbes come into contact with the polymer, water on the surface of the microbes interacts with the sulfonic acid functional groups in the polymer – creating an acidic solution that quickly kills the bacteria,” said Reza Ghiladi, an associate professor of chemistry at NC State and co-corresponding author of the paper. “These acidic solutions can be made more or less powerful by controlling the number of sulfonic acid functional groups in the polymer.”

The researchers testing the polymer against six types of bacteria, including antibiotic-resistant strains such as MRSA, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium, and carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. When 40% or more of the relevant polymer units contained sulfonic acid groups, the polymer was able to kill almost all of each strain of bacteria within 5 minutes.

The researchers also pitting the polymer against some viruses. “The polymer was able to fully destroy the influenza and the rabies analog within 5 minutes,” said Frank Scholle, an associate professor of biological sciences at NC State and co-author of the paper. “While the polymer with lower concentrations of the sulfonic acid groups had no practical effect against human adenovirus, it could destroy 99.997% of that virus at higher sulfonic acid levels.”

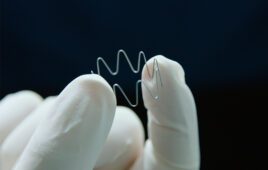

One potential challenge related to the polymer is that its antimicrobial effect could progressively worsen over time, as positively charged ions (cations) in water neutralize sulfonic acid groups. But the researchers think it’s possible to get the polymer “recharged” through exposure to an acid solution.

“In laboratory settings, you could do this by dipping the polymer into a strong acid,” Ghiladi said. “But in other settings — such as a hospital room — you could simply spray the polymer surface with vinegar.”

The researchers’ paper, “Inherently self-sterilizing charged multiblock polymers that kill drug-resistant microbes in minutes,” appeared July 17 in the journal Materials Horizons.