People may like mobile blood pressure apps better when the apps reveal positive results, even if those results are inaccurate 80% of the time, according to a recent study.

People may like mobile blood pressure apps better when the apps reveal positive results, even if those results are inaccurate 80% of the time, according to a recent study.

A team of researchers who previously revealed the inaccuracy of the Instant Blood Pressure (IBP) app returned to the topic to study 81 adults who compared the app’s readings against their own BP estimates. Those whose systolic BP measured lower on the IBP app than they expected reported that they were more inclined to use the app again than those whose systolic blood pressure was higher than they estimated, the study showed.

Dr. Timothy Plante of the Department of Medicine at the University of Vermont in Burlington and Dr. Seth Martin of the Malone Center for Engineering in Healthcare at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore designed both studies and analyzed the data. App developer AuraLife (Newport Beach, Calif.) charged between $4 and $5 for the app on Google Play and iTunes. It was downloaded more than 148,000 times and earned the company more than $600,000.

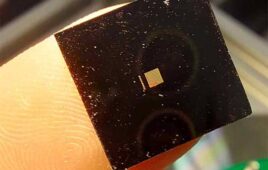

AuraLife’s marketing claimed the app could measure blood pressure simply by placing a cellphone on the chest with a finger. The company also claimed the app could be used to replace around-the-arm cuffs and would be just as accurate as the traditional device, according to a Federal Trade Commission complaint against it. AuraLife settled with the agency for $600,000 and the app disappeared from the market in 2015.

“Given the high popularity and lack of promised functionality, IBP is a prominent example of a ‘snake oil’ app that exposes its users to potential harm through poor functionality,” the authors wrote in the new study, published in npj Digital Medicine. “Understanding the reasons for the high popularity of this inaccurate app will help inform future policy development to ensure a safe app space.”

Among the 81 individuals included in the sample, the mean age was 57 years, 54% were men, and 84% had a smartphone. The results showed that regardless of the app’s readings, users believed they were accurate. Those whose readings were higher than expected reported lower enjoyment of the app and a lower desire to use it again than those who had lower-than-expected readings.

“Our findings are an initial step to understanding the role of user experience in the uptake of mHealth apps,” the authors wrote. “For BP-measuring apps, the primary driver of use from a medical perspective should be accuracy. However, our exploration of user experience suggests that falsely reassuring BP results may play a role in promoting app use.”

Patients without access to a validated BP monitor may rely on unvalidated BP apps to generate inaccurate data and perceptions about their health, according to the authors. “These findings underscore the need to validate high-risk mHealth apps prior to their commercial availability, as well as educate patients and providers about the potential perils of these apps,” they wrote.