(Credit: Marc Delachaux/2016 EPFL Marc Delachaux /2016 EPFL, Phys.org)

An EPFL team is developing soft, flexible and reconfigurable robots. Air-actuated, they behave like human muscles and may be used in physical rehabilitation. They are made of low-cost materials and could easily be produced on a large scale.

Robots are usually expected to be rigid, fast and efficient. But researchers at EPFL’s Reconfigurable Robotics Lab (RRL) have turned that notion on its head with their soft robots.

Soft robots, powered by muscle-like actuators, are designed to be used on the human body in order to help people move. They are made of elastomers, including silicon and rubber, and so they are inherently safe. They are controlled by changing the air pressure in specially designed ‘soft balloons’, which also serve as the robot’s body. A predictive model that can be used to carefully control the mechanical behavior of the robots’ various modules has just been published in Scientific Reports.

Potential applications for these robots include patient rehabilitation, handling fragile objects, biomimetic systems and home care. “Our robot designs focus largely on safety,” said Jamie Paik, the director of the RRL. “There’s very little risk of getting hurt if you’re wearing an exoskeleton made up of soft materials, for example” she added.

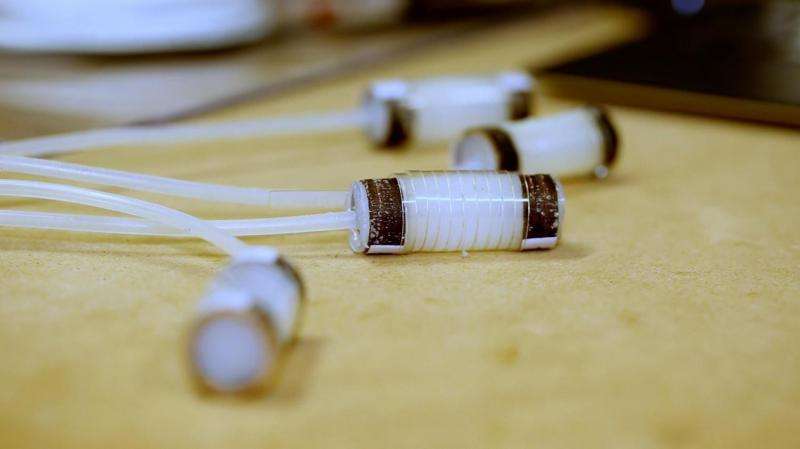

In their article, the researchers showed that their model could accurately predict how a series of modules – composed of compartments and sandwiched chambers – moves. The cucumber-shaped actuators can stretch up to around five or six times their normal length and bend in two directions, depending on the model.

“We conducted numerous simulations and developed a model for predicting how the actuators deform as a function of their shape, thickness and the materials they’re made of,” said Gunjan Agarwal, the article’s lead author.

One of the variants consists of covering the actuator in a thick paper shell made by origami. This test showed that different materials could be used. “Elastomer structures are highly resilient but difficult to control. We need to be able to predict how, and in which direction, they deform. And because these soft robots are easy to produce but difficult to model, our step-by-step design tools are now available online for roboticists and students.”

(Credit: Marc Delachaux/2016 EPFL, Phys.org)

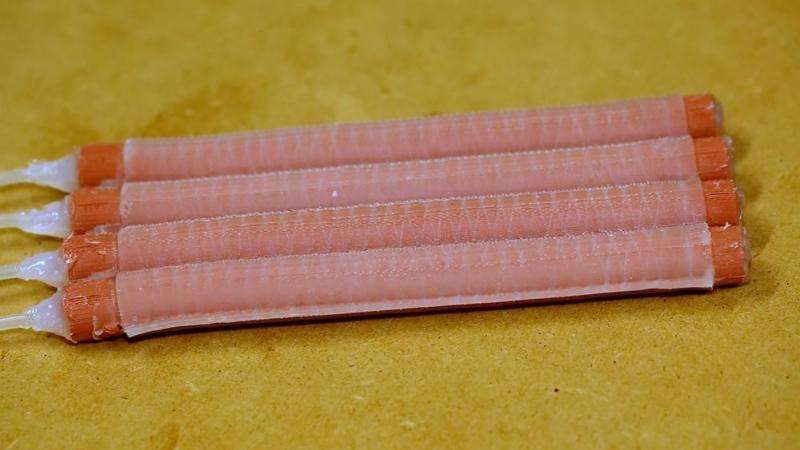

In addition to these simulations, other RRL researchers have developed soft robots for medical purposes. This work is described in Soft Robotics. One of their designs is a belt made of several inflatable components, which holds patients upright during rehabilitation exercises and guides their movements.

“We are working with physical therapists from the University Hospital of Lausanne (CHUV) who are treating stroke victims,” said Matthew Robertson, the researcher in charge of the project. “The belt is designed to support the patient’s torso and restore some of the person’s motor sensitivity.”

(Credit: Marc Delachaux/2016 EPFL, Phys.org)

The belt’s soft actuators are made of pink rubber and transparent fishing line. The placement of the fishing line guides the modules’ deformation very precisely when air is injected. “For now, the belt is hooked up to a system of external pumps. The next step will be to miniaturize this system and put it directly on the belt,” said Robertson.

Potential applications for soft actuators don’t stop there. The researchers are also using them to develop adaptable robots that are capable of navigating around in cramped, hostile environments. And because they are completely soft, they should also be able to withstand squeezing and crushing.

“Using soft actuators, we can come up with robots of various shapes that can move around in diverse environments,” said Paik. “They are made of inexpensive materials, and so they could easily be produced on a large scale. This will open new doors in the field of robotics.”

(Credit: Marc Delachaux/2016 EPFL, Phys.org)