Some surgeons might be able to prescribe a third of opioid painkiller pills that they currently give patients, and not affect their level of post-surgery pain control, a new study suggests.

That would mean far fewer opioids left over to feed the ongoing national crisis of misuse, addiction and overdose.

The findings, published in JAMA Surgery by a team from the University of Michigan, show the power of basing surgery-related pain prescriptions on how patients actually use medicines, and educating both surgical teams and patients on pain control. The U-M team recently launched a site aimed at doing just that.

Since no national guidelines exist for surgery-related pain control with opioids, the team set out to develop one and test it. They started with a common operation: gallbladder removal, also called laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Data from 170 patients treated at Michigan Medicine, U-M’s academic medical center, showed the average patient received a prescription of 250 milligrams of opioid medications, as measured in morphine equivalents. That’s about 50 pills.

But when the researchers interviewed 100 of these patients, the amount of opioid painkiller they’d actually taken after their operation averaged 30 milligrams, or about 6 pills. The rest was often still sitting in their medicine cabinet, even years after their surgery.

When U-M surgical leaders heard these findings, they gave the researchers the green light to develop and roll out a much lower prescribing guideline, paired with a new patient education effort about pain control.

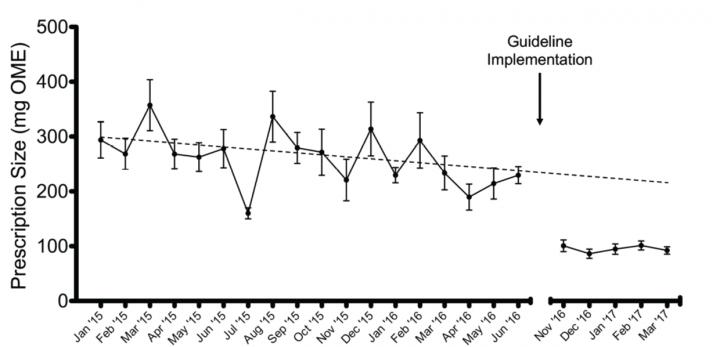

Before the guideline was implemented at Michigan Medicine, the University of Michigan’s academic medical center, gallbladder surgery patients received an average of 250 mg of opioid pain medications. Soon after the guideline went into place, that dropped to about 75 mg — with no change in patients’ self-reported pain scores. (Image credit: University of Michigan)

Interviews with 86 of the patients who received the smaller prescriptions showed they reported the same level of pain control as those treated before — even though they took even less of their opioid medicine, about 20 milligrams.

“For a long time, there has been no rhyme or reason to surgical opioid prescribing, compared with all the other efforts that have been made to improve surgical care,” says first author Ryan Howard, MD, a resident in the U-M Department of Surgery who began the study while attending the U-M Medical School. “We’ve been overprescribing because no one had ever really asked what’s the right amount. We knew we could do better.”

He estimates that just implementing the guidelines at U-M for gallbladder surgery has kept more than 13,000 excess opioid pills out of circulation in the year since the rollout began.

The team stayed on the conservative side with their initial guideline, recommending 15 opioid pills for gallbladder patients.

Howard worked with fellow resident Jay Lee, MD, and transplant surgeon Michael Englesbe, MD, to perform the study and implement the guideline. Armed with the data and interviews from previous patients, they worked with surgical leaders, then met with nurses, physician assistants, residents and surgeons in turn.

“Even though the guidelines were a radical departure from their current practice, attending surgeons and residents really embraced them,” says Lee. “It was very rewarding to see how effective these guidelines were in reducing excess opioid prescribing.”

The team also used the insights gained from patient interviews to redesign patient education materials. For instance, some patients had said they had taken every opioid pill their surgeon had prescribed, because they thought they were supposed to — like a course of antibiotics.

The new patient education guide for gallbladder removal patients counsels them to take pain medicines only as long as they have pain, and to reserve the opioid pills for pain that’s not controlled by ibuprofen or acetaminophen.

“Many patients had told us they wanted to know how many pills they should expect to take,” says Lee. So the guide lays it out: most patients take about five or less, and stop taking pain medicine by the fifth day after surgery.

The guide also emphasizes the need for safe disposal of leftover pills, and gives a link to a map created by the team showing locations across Michigan that take opioids back.

Based on the results, the team decided to take the guideline effort statewide, and increase the number of operations. Using data from patients who had surgery at dozens of Michigan hospitals taking part in the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative, they have developed prescribing recommendations for 11 additional common operations.

Less than two months ago, those recommendations made their public debut via the Michigan Opioid Prescribing and Engagement Network (Michigan OPEN) initiative that Englesbe co-leads. The team notes they’ve been met with a mostly welcoming response from surgeons as an evidence-based basis for prescribing post-surgery pain medicine.

“Pain is an integral part of surgery – we cause pain in the short term so in the long term we can help heal you,” says Howard. “Nearly half of the prescriptions surgeons write are for pain medications, but traditionally we haven’t gotten any training or guidance in it. We hope that this framework we’ve developed can be applied to many more operations.”

The Michigan OPEN team previously found that about 6 percent of surgery patients who receive opioids keep refilling their prescriptions months later — long after their pain should be gone.

They also have published findings based on Michigan-wide data that show that patient satisfaction scores related to pain aren’t linked to the amount of opioids prescribed to surgery patients. The worry that denying patients opioids will decrease satisfaction — and with it the extra payment that hospitals get from Medicare based on satisfaction scores — has been a constant refrain when the U-M team has spoken to gatherings of surgical professionals.

Englesbe, a professor in the U-M Department of Surgery, is aiming even lower when it comes to opioids.

“We continue to notice that with education and attentive care, fewer and fewer opioids are needed and pain care is improving,” he says. “Our ambitious goals include empowering half of the surgical patients at Michigan Medicine to be opioid-free following the first day of surgery.”

In addition to Howard, Lee and Englesbe, the study’s authors are the other two directors of the Michigan-OPEN initiative, Jennifer Waljee, MD, MS, and Chad Brummett, MD.