Last year, Carolina Panthers linebacker Thomas Davis showed off a new bit of equipment during Super Bowl 50 – a 3D-printed brace that helped protect Davis by providing shock absorption for the player’s healing forearm.

Last year, Carolina Panthers linebacker Thomas Davis showed off a new bit of equipment during Super Bowl 50 – a 3D-printed brace that helped protect Davis by providing shock absorption for the player’s healing forearm.

“That was quite the project, and we weren’t expecting it,” says Jerry Ropelato, CEO of Whiteclouds, the company that helped design the brace, noting a tight deadline. “We got the first notification and two hours later we got the scan. We didn’t have months to figure it out. We had a 31 hours to print.”

Some of the challenges Ropelato describes for the brace were outside of the norm. “It was a bit more than a typical design, because we had to ensure we captured the strength and the rigidity needed, but also flexibility to absorb a hit beyond a normal cast. We had to figure out where to place the holes and we felt this couldn’t be a typical [selective laser sintering].”

Less than 72 hours after the first scan was received, Davis had his new brace and was able to practice with it on the field before the game.

Ropelato says the project helped Whiteclouds gain national attention, highlighting its proprietary technology for 3D printing. The company’s cloud-based software is designed to transform 2D images into 3D-printable designs – a task that’s not as easy as it sounds. Essentially, the WhiteClouds software creates models based on 2D images from CT images and other DICOM files. “The biggest challenge is segmentation,” says Ropelato. The software and the processes are complex; it often takes 30 to 40 hours just to create the slice layers. “They have to be no more than 2mm or smaller,” he says.

It also takes a lot of training. Ropelato says many Whiteclouds engineers need a year of training to get up to speed. “We cull all of that capture data and we transform them into modeling software, during which we assign coloring and texture and other aesthetics of the model. It is a laborious task.” Whiteclouds is putting a lot of resources into automating those techniques, to make the overall process faster.

The company acquired 3PlusMe in December 2015 “to help with some of those back-end systems.”

There’s a lot of clear field ahead for Whiteclouds and 3D printing, Ropelato says, noting that “there were 233 million CAT scans, MRIs and ultrasounds performed in the U.S. last year.” Three-dimensional printers work with both medical device manufacturers and hospitals to improve the ability to make surgical models, surgical guides, hand tools, and implants.

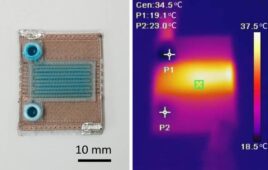

Whiteclouds is also focused on creating models designed to give surgeons insight on a patient’s anatomy and create a practice model. The models also help physicians connect with patients by demonstrating the process, which can help them feel more comfortable about a surgical procedure. “The Phoenix Children’s hospital uses medical models with the families of children who have to go through heart surgery. It really helps to empower patients and their families. It also helps surgeons practice and plan out surgical process,” Ropelato says.

There are some barriers to 3D printing in medical, mostly bureaucratic, he adds.

“Many hospitals are in the early stages on planning and they don’t want publicity yet. They still have to figure out the procedures and processes,” he notes. Wider adoption of medical models and a reimbursement structure for them from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services would also help, Ropelato says. “Right now, hospitals are paying out of pocket in some cases.”

For Davis, who broke his arm during the NFC Championship game against the Arizona Cardinals, things worked out fine – after surgery to repair the break, he was able to play with the Panthers in the Super Bowl, thanks in no small part to the brace printed by Whiteclouds.

Heather, great article but you may want to change that last line in the article. Denver actually beat Carolina in the Super Bowl. 🙂

I knew it! My editor lead me astray and I didn’t fact check… That’s what I get 🙂