Among other accomplishments, Paul Alan Wetter, MD, FACOG, FACS, is the chairman of the Society of Laparoscopic Surgeons (SLS), a position he’s held for over two decades. At the recent Minimally Invasive Surgery Week, the organization’s annual conference bringing together practitioners from a wide variety of surgical disciplines, Wetter sat down with Surgical Products to discuss the conference, the work of SLS, and the general state of modern medicine.

More from this interview will appear in a future issue of Surgical Products.

Tell us about the Minimally Invasive Surgery Week meeting.

It’s a group effort. SLS is a nonprofit organization that was started almost 30 years ago to educate and provide information on minimally invasive surgery. It’s a multi-specialty organization, and those are more unusual. A lot of the specialties have become compartmentalized. There’s information that different specialties don’t always have access to, so by bringing all the specialties for minimally invasive surgery together in one location there’s a lot of cross-pollination of ideas and people learning things that are useful that we’re not learning about in our specialty-specific organizations. The people who come here are the people who are really interested in being at the forefront, in providing the best patient care on a surgical basis.

You’re connecting surgeons who don’t often get to interact with each other. How significant is that component?

There’s a great book that came out recently by Judge Harry Rein. He’s a physician, lawyer, and judge. He wrote about his life and career. He noted that back in the 1950s the surgeons would go in the surgeon’s lounge, and they’d be talking about what type of suture they’re using, what works best for things. Because of financial issues, reimbursement issues, malpractice issues — all these things — those conversations have totally shifted. There’s a little bit of that, but not like there used to be. Today, people are very concerned about the medical legal climate and things like that. We’re really missing connections that were there before. So a meeting like this is good in that instance.

At the conference, we had a mock OR — it was really well attended, everyone was very excited. On the stage, we had a complete operating room set up with a group of surgeons as actors. They would be working, and we’d add a playacting complication. They would then stop and discuss it. They’d have the hospital administrator there, the person who is medical legal there. They had a psychiatrist, Dr. Daniel Kuhn, to discuss the stress of the family and the physicians. Now these were all play-actors who were physicians who came together to do this program. But these were all real physicians, real safety officers, real psychiatrists, working together on this one case. And when things went wrong, we saw how they really handled it: what you should do, how you should act, what the stresses are. Every physician that has a serious complication or death, it’s devastating to them psychologically, emotionally. These are people who devote their whole lives to helping others, and when they have a complication — even a small one — it’s emotionally difficult. It’s traumatic to the surgeon just as it is to the patient and the family. And so they discussed all of these issues and how you can work through them, including the best way to interact with the patient, which isn’t taught in a lot of places. So that’s an example of the benefit of a multidisciplinary focus. We can bring everybody together to work on those things. It was a great session which everybody liked. I’m sure we’ll do it again.

You mentioned communication skills, specifically between the physician and the patient. There’s been some recent discussion about challenges surgeons have in those sorts of interactions, especially when it comes to adverse events.

It’s accurate and it’s ultimately important. People always refer to medicine as an art and a science. I’ve started to think about it very, very differently. The art of medicine is not that everybody treats things differently, because if it’s a true science every physician that you see should give the same diagnosis, which is the best diagnosis. Every physician you see should give you the same treatment, which is the best treatment. And that’s not the case today. You go to five different physicians, you’ll get five slightly different diagnoses, or the same diagnosis but slightly different ways of treating it. To me, medicine should be like other sciences. If you asked a astrophysicist how to get to the moon, they all use the same math. They all can get you to the moon, and they use the same kind of math to do it. And if they use the same trajectory, it’s the same answer. The science of medicine should be that way. The art of medicine should be your ability to communicate with the patient. Hopefully we’ll get there with outcome studies and assessing which treatments get better outcomes and then publishing those things.

We’re doing a lot of that in our JSLS journal. Our journal is very unique. Our society is also the publisher of our journal, so we’re one of the few nonprofit publishers of a medical journal. All our articles are open access. They go right to PubMed Central, where they’re accessible to 5000 medical libraries in the United States. That’s the first place everyone looks, so last year we had over 1,200,000 downloads, which is unprecedented. We think this is the model that’s the right model to have for medicine. It gets good, important scientific information out there quickly, and it’s available to all the medical libraries. All of the universities want this. The government wants it. When somebody’s doing research and they come up with something that’s important, they want it to not be sequestered on a publisher’s website for six months. They want it to be open access so anybody can find it quickly. We are the number one MIS journal worldwide now because of this unique model.

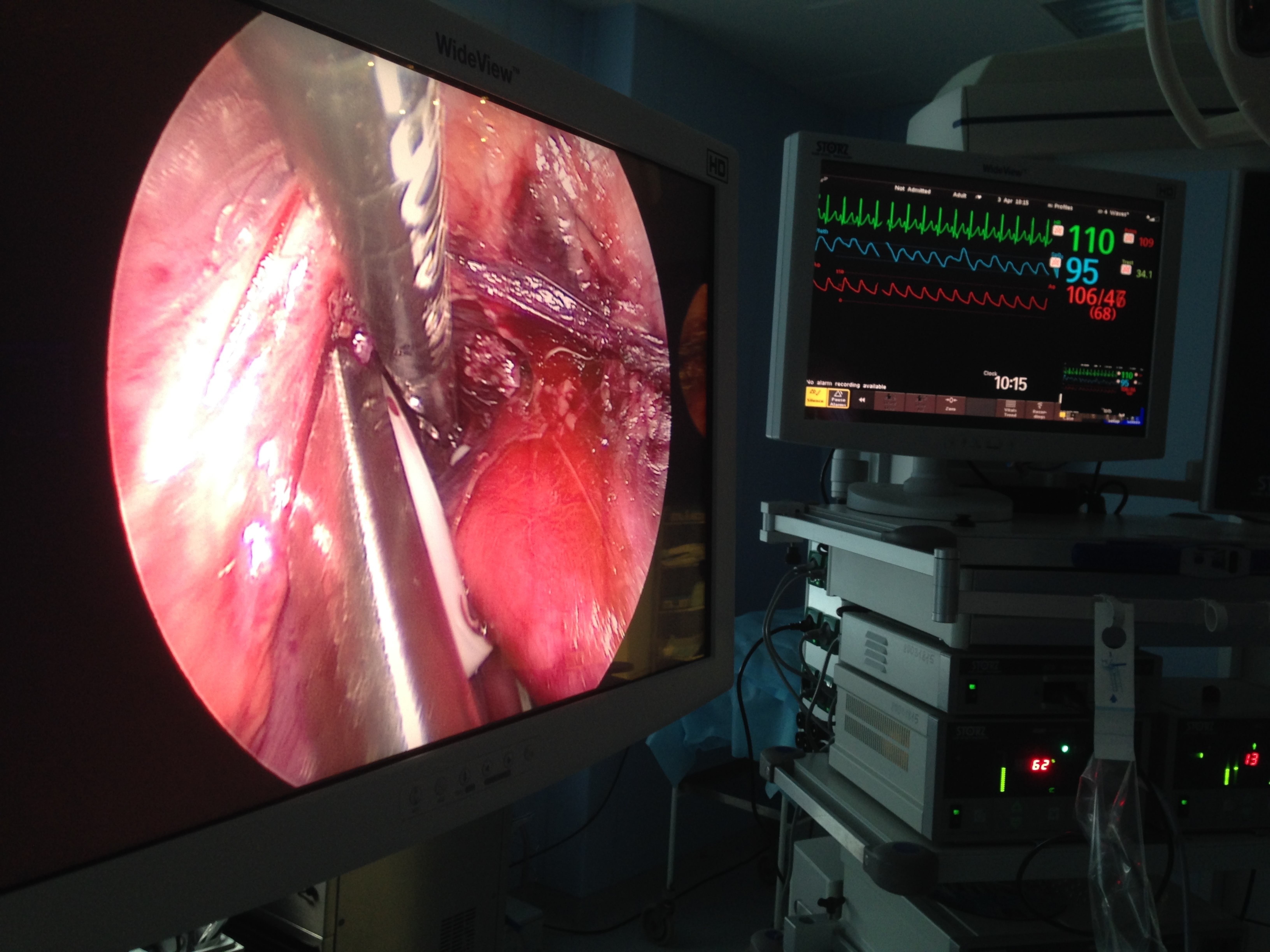

Participants at MISWeek 2016. (Image credit: SLS)

That also helps you get the information to places and physicians that might not otherwise have access, doesn’t it?

Exactly. And it’s our philosophy. We’re a nonprofit organization. We’re not a big for-profit company. So the U.S. government has given us the right to develop things as a nonprofit organization for the public good. And there is a responsibility that goes along with that. And it’s good if we can provide information and education that’s useful and tear down the barriers to it so that a surgeon in a poor town in Arkansas can get that information. Probably 99 percent of what’s on the website, you don’t even have to be a member to access it. You just go there and you can search and find the information from our textbooks, from our journals. And our members support that. They realize that’s a worthy way to do this. If you’re paying dues to an organization and you know that that money is going to helping not only you but other people and other physicians all around the world, you feel good about that.

Any final thoughts?

Medicine today is still one of the most exciting fields. The potential of things out there that we can utilize to give better healthcare to patients is really unlimited and changing all the time. It’s a very, very exciting time to be involved in healthcare and in medicine.