[Image from University of Missouri School of Medicine]

Postgraduate physician training is a time for physicians to develop skills and expertise within the medical specialty of their choosing. While training, medical school professors evaluate their clinical competency, confidence and decision-making skills based on observations.

“Within surgical education, skill evaluation is based on a subjective assessment, which essentially is a gut feeling,” said Jacob Quick, assistant professor of acute care surgery at the MU School and Medicine and a lead author on the study, in a press release. “There is a need for an objective, impartial way to determine surgical ability and a resident’s capacity to operate independently. We monitored electrodermal activity during actual surgical procedures. We hypothesized that as training progressed, resident responses to the stress of performing surgical procedures would decline in relationship to their experience level.”

Electrical activity conducted across the skin is triggered by psychological or physiological stimulation. Sympathetic nervous system-controlled glands produce sweat, which happens to be a conductor of electrical activity, that can measure emotional and sympathetic responses to stress through electrodermal activity (EDA).

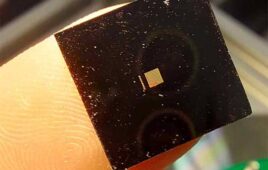

“Essentially, the more nervous we are, the more we sweat,” said Quick, who is also a trauma surgeon at MU Health Care. “The more we sweat, the more electrical activity is conducted across the skin. We used skin response sensors worn by residents to monitor their EDA while they performed laparoscopic gallbladder surgeries.”

The study consisted of 14 general surgery residents and 5 faculty physicians over an 8-month period. Responses of 130 surgical procedures were measured with EDA and the results were compared to determine which parts of the procedure had different levels of EDA responses for the surgeons.

“Our initial findings indicated that at crucial points during the procedures, residents’ EDA increased as much as 20 times more than experienced faculty performing the same surgery,” said Quick. “However, over the course of the study, and as their proficiency developed, surgical residents’ EDA levels began to lower in accordance with their experience.”

Quick suggested that the next step for better evaluations will be to add stop-action photography to explore objective assessments and that EDA may not even become the standard any time soon.

“This type of monitoring is relatively easy to accomplish,” said Quick. “It can be cost prohibitive, though. While the sensors are reusable, initial equipment costs can be as much as $10,000. Additionally, our study was limited to 14 resident physicians at a single medical center. However, this objective measure of surgical ability could have far-reaching implications on surgical education in the future.”

The study was published online in the Journal of Surgical Education and was supported by the Association of Program Directors in Surgery and the Association for Surgical Education.

[Want to stay more on top of MDO content? Subscribe to our weekly e-newsletter.]