[Image from UCSD]

The temperature sensor, developed by electrical engineers at UCSD, uses about 628 times lower power than state-of-the-art power sources and is 10 billion times smaller than a watt. Considered “near zero power,” the engineers suggest that the temperature sensor could extend battery life in a variety of wearable or implantable devices that measure body temperature. It could able be used to create a new class of devices that is capable of harvesting its energy from the body or surrounding environments.

“Our vision is to make wearable devices that are so unobtrusive, so invisible that users are virtually unaware that they’re wearing their wearables, making them ‘unawearables.’ Our new near-zero-power technology could one day eliminate the need to ever change or recharge a battery,” said Patrick Mercier, an electrical engineering professor at UCSD Jacobs School of Engineering and the study’s senior author, in a press release.

The goal of this project was to boost energy efficiencies of individual parts on an integrated circuit to reduce the power requirements on a whole system.

“We’re building systems that have such low power requirements that they could potentially run for years on just a tiny battery,” said Hui Wang, an electrical engineering Ph.D. student in Mercier’s lab and first author on the study.

For example, temperature sensors on healthcare devices have power requirements of as low as tens of nanowatts. The new approach reduces power in the current source and the conversion temperature to a digital readout, making temperature sensors up at 628 times less power.

Researchers used “gate leakage” transistors to build an ultra-low power current source. Usually, gate leakage is a problem in microprocessors and precision analog circuits because the gate material is too thin and can’t block electrons from leaking through. But the researchers are using that to their advantage.

“Many researchers are trying to get rid of leakage current, but we are exploiting it to build an ultra-low power current source,” Hui said.

Using the low-power source, the researchers created a way to digitize temperature without consuming a lot of energy. Normally, as temperature changes, so does its resistance. Then they measure the resulting voltage and convert it to its corresponding temperature using a high power analog to digital converter. In the low-power method, researchers can directly digitize temperature by using two ultra-low power current sources: one that charges a capacitor in a time frame regardless of temperature and one that charges at a rate that changes with temperature. The lower the temperature, the slower the charge. The higher the temperature, the faster the charge.

As the temperature changes, the system detects the change and the temperature dependent current source charges in the same amount of time that the fixed one charges. A digital feedback that gets built in equalizes the charging times and reconnects temperature dependent current sources with a capacitor of a different size.

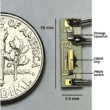

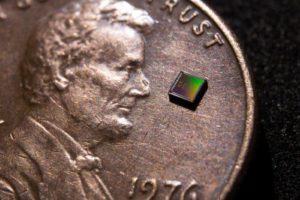

The sensor is built into a 0.15-by-0.15 sq mm chip that can operate at temperatures ranging from -20 ºC to 40 ºC. It has a response time of one update per second, which is slightly slower than other sensors but is still suitable for the human body.

The researchers plan to improve the accuracy of the sensor and optimize the design so it can be used in commercial devices.

The research was published online in the Scientific Reports journal.

[Want to stay more on top of MDO content? Subscribe to our weekly e-newsletter.]