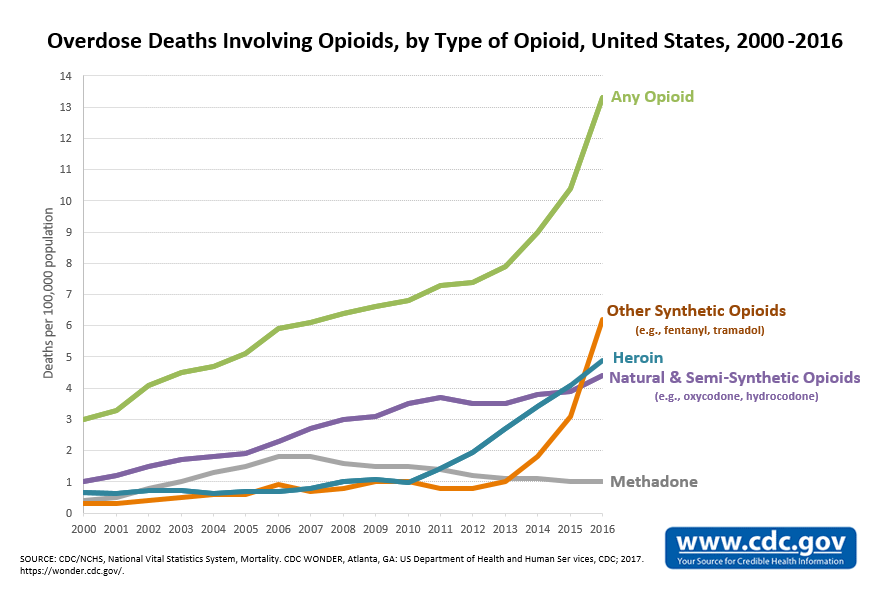

As the United States continues to grapple with the opioid epidemic — the mightiest drug scourge in the nation’s history — another crisis is emerging in its wake.

Doctors are increasingly wary of dispensing narcotics and prescription rates are falling (prescription rates were down 13 percent between 2012 and 2015, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Physicians are not just afraid of contributing to addiction rates. There’s also a growing body of research suggesting that available alternatives to opiates are either just as effective or even more so in various healthcare scenarios — from injuries to chronic pain.

Yet, for many patients struggling with daily pain, current treatments are often not enough and the sudden tightening of opioid prescriptions is doing more harm than good. Thus, the gap between those who are suffering and those finding adequate treatment is widening.

While doctors and patients scramble to solve this growing conundrum, the potential for a new pain medication to reach blockbuster status has never been greater.

According to the World Health Organization, about 116 million Americans were living with chronic pain in 2011, and the market potential for a number of painful illnesses is expected to skyrocket in the coming years. Transparency Market Research predicted last year that the global market for “pain management therapeutics” will grow from $60.2 billion in 2015 to $83 billion by 2024.

Naturally, many pharmaceutical companies have sensed for years that more therapies are going to be needed and are hunting for new molecules to alleviate pain or looking into different pathways to block pain signals from reaching the brain. While progress has come in fits and starts, the regulatory environment is favorable for moving promising therapies down the pipeline.

In short, opiate addiction rates in the U.S. are still at devastating highs. Doctors are often too nervous to prescribe narcotics and don’t have great alternatives to offer. Many patients are struggling. The race to find the next great painkiller is on.

What kinds of treatments are coming down the pipeline that could finally offer relief without the risk of a crippling addiction? Where are pharmaceutical companies finding the most hope and seeing the most opportunity to make a big move in the market?

Drug-Free Relief

Attitudes around medical devices are shifting as doctors look beyond pills to treat pain.

Though once taboo, demand is now increasing for small spinal implants that counteract pain signals, spurring manufacturers to innovate more efficient models of the devices.

One device made by Abbott Laboratories that stimulates the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) has shown promise in reducing the need for opioids for patients suffering from complex regional pain syndrome. The condition is not well understood, but it often arises after arthroplasty, foot or hernia surgery. The condition is so excruciating that doctors have nicknamed it the “suicide disease” due to the high number of patients who eventually take their own lives.

Of all the Americans suffering from chronic pain conditions, healthcare research firm Decisions Resources Group estimates that just 3.7 million would benefit from spinal implants like Abbott’s DRG device. Yet, the firm predicts that the market could balloon from $1.8 billion now to $4 billion within 10 years.

Local analgesics have also been developed to treat post-operative pain and reduce opiate use. Last year, Pacira Pharmaceuticals announced promising results from a Phase 4 study using their product called Exparel, a long-acting analgesic containing liposomal bupivacaine that is placed directly into surgical sites. According to the company, 78 percent of the patients using the product in the study decreased opioid use, compared to bupivacaine HCI, the traditional local analgesic.

Pacira, which tested the new product on patients who had undergone total knee arthroplasty, says Exparel can be used for patients who have undergone numerous procedures, from hysterectomies and C-sections to colon, hip, spine, foot surgeries and more.

Exparel delivers pain relief through single-dose infiltration into the surgical site to produce postsurgical analgesia. (Image credit: Pacira Pharmaceuticals)

Innovations like these are not only proving to be suitable for replacing opioids — in some cases it they even seem to work better.

“When we first started using opioids to treat pain we thought the biggest problem was addiction. But really the biggest problem is that they don’t work,” Dan Clauw, the director of the Chronic Pain and Fatigue Research Center at the University of Michigan, says. “Now when you look at non-drug therapies there is better and better evidence [they are effective] and they’re often less expensive.”

Next-Generation Opioids

There’s no denying that many care providers still see opioids as the go-to solution for treating acute severe pain. The challenge for researchers is finding a way to harness the pain-relieving properties of opiates while eliminating potentially harmful side effects that could lead to addiction or overdose.

James Zadina, a researcher at the Tulane School of Medicine and the Southeast Louisiana Veterans Health Care System, has been working for years to do just that.

In 2016, Zadina and his team published a report in Neuropharmacology showing that they had successfully treated pain in rats using a peptide-based drug that targets the same pain-relieving opioid receptor as morphine while avoiding common opioid side effects including motor impairment, respiratory depression, and rising tolerance — which can often lead patients to increasing their dosages, setting them on a path to addiction.

While the results are promising, Zadina’s drug would likely still trigger a mild euphoria similar to other narcotics, which would mean the potential for abuse could still be high. But Zadina’s team has been working with investors and biotech companies to develop the treatment further and seek approval for human trials.

Researchers are also developing drugs that act on multiple pain-relieving receptors, including mu, delta, and kappa. Opioids typically target the mu receptor, which is what triggers an opioid “high” along with an increased tolerance.

One team at the University of Maryland has created a drug called UMB425 that hits both the mu and delta receptors, which, for reasons that aren’t clear, eliminates several side effects including rising tolerance.

Just like the drug being developed by the group at Tulane, however, the medication still produces euphoria. It also has been tested only in rodents and could be years away from human trials.

Another drug that’s gotten a lot of buzz is PZM21, a synthetic opioid that was discovered by a team of scientists from four universities after they screened more than 3 million chemical compounds using computer modeling. Studies on mice showed that the pain-relieving properties of the compound last longer than morphine and didn’t cause respiratory depression.

Trevena has also developed a new opioid called oliceridine that has been given breakthrough therapy designation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration — putting the drug on the fast track to approval. The medication, which is in human trials, also treats pain without the same dangerous respiratory side effects as morphine, but also has similar addictive-like properties.

New Targets

“I would say that the next class of drugs coming out in the next few years are nerve growth factor antibodies,” says Clauw.

Chronic pain sufferers often have higher nerve growth factor levels, which interact with tropomyosin receptor kinase A to moderate pain. The hope now is that researchers can develop drugs to block this interaction.

According to Clauw, one of the most promising therapies is tanezumab, a drug being developed by Pfizer and Eli Lilly. The medication is currently in Phase 3 clinical trials for low back and chronic pain. But, if effective, the biggest prize would be for osteoarthritis treatment.

“That is the main gorilla of the pain market because almost everyone will develop osteoarthritis,” Clauw says.

One of the biggest hurdles for new biologics, however, will be the cost.

“The average biologic starts at $20,000 to $30,000 and goes up,” Clauw says. “The analgesic space has never seen anything like that for cost.”

Cues From Nature

Some scientists are finding that nature provides plenty of answers for treating pain, if you’re willing to look close enough.

A sea snail species that grows to be just 2.5-3.8 cm long, for example, has become one of the latest targets by researchers looking to harness toxic venoms for analgesics. Late last year, researchers from the University of Utah announced that they were given a $10 million grant to study a group of cone snails to “identify new, natural compounds to develop non-opioid drugs for pain management.”

Although there are hundreds of species of the cone snails, the team will likely hone in on the subgenus Conus asperella, which uses its harpoon-like tooth to stab its prey and flood them with a paralyzing venom.

The team, led by Toto Olivera, is hoping to identify the numbing compounds and use them to make new drugs. But because it can take an average of 10 years to produce a medication from a natural toxin, it could be some time before the team has a treatment that’s ready for trials.

Cone snails are just one of many exotic creatures scientists are studying in the burgeoning field of venom research. Researchers are also looking into a type of fish known as the sabretooth benny, which stabs victims with a heroin-like substance to impair them.

The Sodium Route

Another kind of venom — this time from a Chilean tarantula — could hold the key to alleviating pain associated with chronic conditions and an extremely rare illness called inherited erythromelalgia, which is associated with the SCN9A gene. People who have a hyperactive mutation of the gene feel excruciating pain at slight temperature changes or with other minor stimulation. Conversely, those with a rare loss-of-function with the gene feel no pain at all.

Researchers at the biotech company Amgen are developing a medication derived in part from Chilean tarantula venom. (Image credit: Domser at de.wikipedia/Wikimedia Commons)

Scientists have discovered that the gene affects sodium channel NaV1.7, which sends pain signals to peripheral nerve cells. Importantly, effectively blocking these pain signals would avoid tampering with signals that travel to the brain — which would avoid many of the negative consequences associated with opioids.

Amgen, a biotech company, is currently developing a medication from the tarantula venom that targets NaV1.7. Swiss pharmaceutical company Roche has also created two molecules aimed at NaV1.7 that have already passed Phase 1 clinical trials. Several other companies including Biogen, Regeneron, and Vertex also have drugs in development that target NaV1.7 or other sodium channels.

The sodium channel route has experienced roadblocks, however. Last summer, Teva and Xenon announced that a compound called TV-45070 that targets NaV1.7 didn’t meet midstage clinical trial goals for chronic pain conditions. Johnson & Johnson and Pfizer have also abandoned their hunt for NaV1.7 drugs.

And because NaV1.7 is also found in cells that provide users with a sense of smell, numbing this sodium channel could trigger a loss of smell as a side effect.

While pressure mounts in the U.S. to quickly end the current epidemic of addiction and overdoses, doctors are eager to have at least one non-addictive tool for severe pain management at their disposal. And in 2018 and beyond, the search for cost-effective alternatives to opioids continues.

A version of this article appeared in Pharmaceutical Processing and in the January/February 2018 issue of Surgical Products.