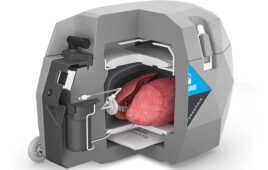

Research subjects at the University of Minnesota fitted with a specialized noninvasive brain cap were able to move the robotic arm just by imagining moving their arms. [Photo courtesy University of Minnesota College of Science and Engineering]

“This is the first time in the world that people can operate a robotic arm to reach and grasp objects in a complex 3D environment using only their thoughts without a brain implant,” said University of Minnesota biomedical engineering professor and lead researcher on this study Bin He.

The technique is called electroencephalography (EEG) based brain-computer interface. It records weak electrical activity in the brain through an EEG cap that has 64 electrodes—no surgical implants needed. The cap converts what the user is thinking into operation with advanced signal processing and machine learning.

Eight humans were a part of the experiment. The subjects had to wear an EEG cap and only think about moving their arms to be able to control a robotic arm. The robotic arm was used in a 3D space to grasp and move objects from a table to a shelf, using only the thoughts of the person wearing the EEG cap.

“Just by imagining moving their arms, they were able to move the robotic arm,” said He.

Every subject was able to control the robotic arm and move object to a designated location with an 80% success rate. Moving objects from a table to a shelf resulted in a 70% success rate.

“We’re happily surprised that it worked with a high success rate and in a group of people,” said He.

The brain-computer interface technology works because of the location of the motor cortex of the brain. Neurons from the motor cortex create electric currents when humans move or think about moving. New neurons are released when people think about a different movement. He figured out how to filter through the neurons with advanced signal processing and was able to correctly interpret the intended motions the brain was trying to convey.

People who suffer from neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s, Huntington’s and spinal muscular atrophy may benefit from this research.

The full research from the University of Minnesota was published on the Nature Scientific Reports website.

[Want to stay more on top of MDO content? Subscribe to our weekly e-newsletter.]