Advances in catheter components are paving the way for improved, more sophisticated devices. A super-thin-walled PTFE catheter base liner presents new opportunities for smaller devices. MRI-compatible LCP braiding is stronger than previous non-metal braidings and rivals the strength of some stainless steel braidings.

Kevin Bigham, Zeus

(Image courtesy of Zeus)

Vascular catheters are paramount for non-invasive surgeries, serving as the working channels through which other devices or therapies are passed to treat blocked vessels and other vascular maladies. Tools such as atherectomy devices, stents, cameras, ultrasound and irrigation devices can be precisely placed in the treatment zone using catheters.

Basic components

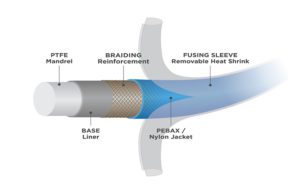

While there are many variations, catheter construction principally involves five basic components – mandrel, base liner, braiding reinforcement, jacket and a fusing sleeve. These components provide opportunities to create clever and innovative refinements to improve catheter function, including design for ever-smaller vasculatures. Several recent developments in this area make it incumbent to review basic catheter construction and highlight a few of these latest innovations.

Thinner and smaller

The first component placed upon the mandrel during catheter construction is the base liner, typically a thin-walled tubing polymer extrusion that forms the interior wall of the finished catheter. PTFE is the preferred liner material because of its chemical inertness within the body and very low coefficient of friction. It also provides an extremely lubricious PTFE-PTFE interface between the liner and mandrel, enabling easy mandrel removal at the conclusion of construction.

Most recently, extremely thin-walled PTFE liners have become available, fostering even smaller finished devices. The thinnest liners can be produced with wall thicknesses as low as 0.00075 in. (0.01905 mm). With the constant drive toward smaller devices, these super-thin-walled liners enable greater lumen potential than ever before while supporting microcatheter sizes that can reach the smallest vasculatures, even those bordering on neurovascular networks.

MRI-compatible catheters

Following the catheter base liner is a braiding to provide additional strength. The braiding is typically some form of stainless steel, nitinol or other biocompatible metal. Such braiding can take a variety of forms and pick counts to tailor mechanical properties of the device.

However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) precludes the use of most metals used in catheter construction. Liquid crystal polymer (LCP) monofilament braiding, a newly developed alternative to metal, has taken on the challenge of MRI-compatibility. LCP possesses many beneficial properties for catheter braiding, including autoclavability, chemical resistance, mechanical properties that rival some stainless steel braidings, and diameters as small as 0.002 in. (0.051 mm).

Above all, LCP is MRI-compatible: It is not metal. This extremely strong monofilament has been used in prototype catheters and has received highly favorable results. LCP also supports the construction of small devices because it may be produced with very small diameters. LCP monofilament opens the door for the first widely accepted, truly MRI-compatible catheters for minimally invasive procedures.

Kevin Bigham earned bachelor’s degrees in chemistry and biochemistry at the College of Charleston and a PhD in biomedical and pharmaceutical sciences at the Medical University of South Carolina. He has worked in manufacturing and research and is a technical writer for Zeus.

The opinions expressed in this blog post are the author’s only and do not necessarily reflect those of Medical Design and Outsourcing or its employees.