(Credit: Worcester Polytechnic Institute)

A chip developed by mechanical engineers at Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) can trap and identify metastatic cancer cells in a small amount of blood drawn from a cancer patient. The breakthrough technology uses a simple mechanical method that has been shown to be more effective in trapping cancer cells than the microfluidic approach employed in many existing devices.

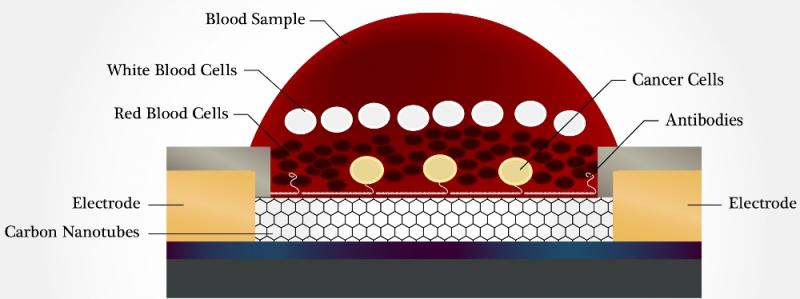

The WPI device uses antibodies attached to an array of carbon nanotubes at the bottom of a tiny well. Cancer cells settle to the bottom of the well, where they selectively bind to the antibodies based on their surface markers (unlike other devices, the chip can also trap tiny structures called exosomes produced by cancers cells). This “liquid biopsy,” described in a recent issue of the journal Nanotechnology, could become the basis of a simple lab test that could quickly detect early signs of metastasis and help physicians select treatments targeted at the specific cancer cells identified.

Metastasis is the process by which a cancer can spread from one organ to other parts of the body, typically by entering the bloodstream. Different types of tumors show a preference for specific organs and tissues; circulating breast cancer cells, for example, are likely to take root in bones, lungs, and the brain. The prognosis for metastatic cancer (also called stage IV cancer) is generally poor, so a technique that could detect these circulating tumor cells before they have a chance to form new colonies of tumors at distant sites could greatly increase a patient’s survival odds.

Panchapakesan, right, and postdoctoral researcher Farhad Khosravi with prototypes of the liquid biopsy chip. (Credit: WPI)

“The focus on capturing circulating tumor cells is quite new,” said Balaji Panchapakesan, associate professor of mechanical engineering at WPI and director of the Small Systems Laboratory. “It is a very difficult challenge, not unlike looking for a needle in a haystack. There are billions of red blood cells, tens of thousands of white blood cells, and, perhaps, only a small number of tumor cells floating among them. We’ve shown how those cells can be captured with high precision.”

A cross section of one of the wells in the WPI device, showing how cancer cells sink to the bottom of a blood sample, where they are captured by antibodies bound to carbon nanotubes. The bound cells trigger an electrical response, which is detected by the electrodes. (Credit: WPI)

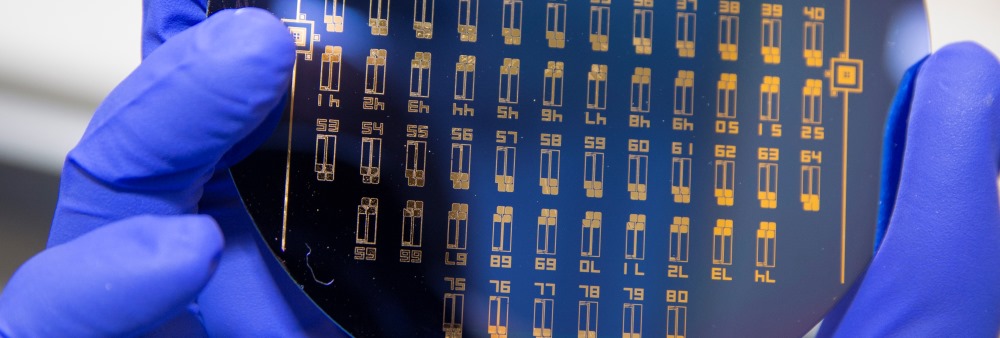

The device developed by Panchapakesan’s team includes an array of tiny elements, each about a tenth of an inch (3 millimeters) across. Each element has a well, at the bottom of which are antibodies attached to carbon nanotubes. Each well holds a specific antibody that will bind selectively to one type of cancer cell type, based on genetic markers on its surface. By seeding elements with an assortment of antibodies, the device could be set up to capture several different cancer cells types using a single blood sample. In the lab, the researchers were able to fill a total of 170 wells using just under 0.3 fluid ounces (0.85 milliliter) of blood. Even with that small sample, they captured between one and a thousand cells per device, with a capture efficiency of between 62 and 100 percent.