The recent Federal Circuit case American Axle Manufacturing v. Neapco Holdings LLC points out potential pitfalls for medical device manufacturers who are not cautious about how certain inventions are claimed in patents.

The front of U.S. Supreme Court in Washington, D.C. (Adobe stock photo)

Christopher Johns, Anthony Del Monaco and Eric Raciti, Finnegan

Recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions have made it more difficult to obtain patents. The courts are now using an “I-know-it-when-I-see-it” test for patent eligibility. This test had largely been confined to computer-implemented inventions and medical diagnostics, but in recent years has infiltrated all areas of patenting.

A recent case illustrates the potential risk to medical device manufacturers because of this shift. Careful claim drafting, however, can help to avoid the patent eligibility question.

The eligibility test (known as the “Mayo/Alice” test) can be summarized briefly as:

- Determine whether the patent claims a “judicial exception” to patent eligibility, such as an abstract idea, law of nature or natural phenomenon, and

- Determine whether the patent claims something “significantly more” than any identified judicial exception.

If this sounds vague to you, you are not alone. The Supreme Court failed to clarify what it meant by “significantly more,” and the lower courts and the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office have increasingly put more and more technological innovations in the broader “judicial exception” bin.

Most of the recent high-profile Supreme Court cases regarding patent eligibility have dealt with patents claiming concepts or properties of nature or science: software patents implementing the abstract concept of intermediated financial settlement (Alice in 2014) and hedging risk (Bilski in 2010), patents for drug administration requiring the application of a “natural law” to determine whether or not to increase dosage (Mayo in 2013), or patents for converting binary-coded numbers into binary numbers (Benson in 1972).

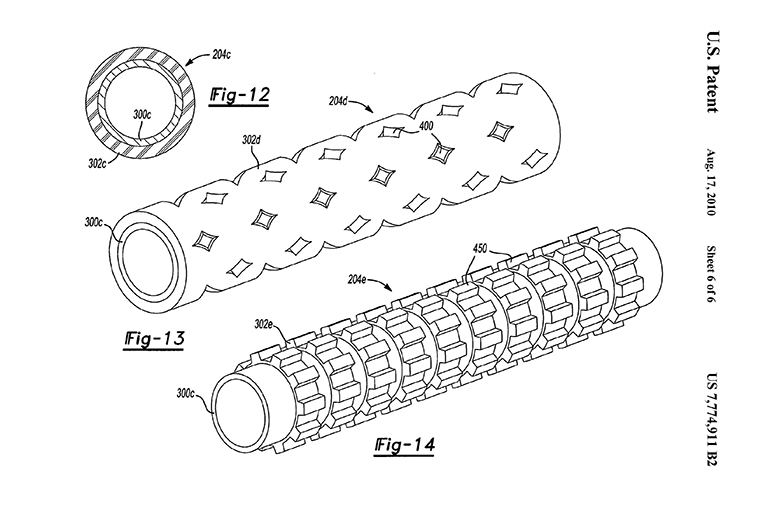

On July 31, 2020, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit issued a revised opinion in American Axle & Manufacturing, Inc. v. Neapco Holdings LLC, finding method claims drawn to manufacturing a liner assembly for a driveline system ineligible as requiring the application of a natural law. Example liners are depicted in Figures 12-14 of the patent:

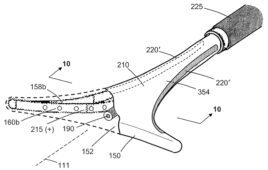

(Image courtesy of Finnegan)

The claims required, among other things, “tuning a mass and a stiffness of at least one liner” in such a way as to attenuate shell-mode vibrations and bending-mode vibrations of a driveshaft. The control of these characteristics to match a frequency would dampen vibration while the shaft rotates.

The court found that the claims required only “controlling characteristics,” such as mass and stiffness of the liner, to configure it to match a relevant frequency or frequencies. In the mind of the court, the claims didn’t specify how these characteristics would be controlled. The decision found that the claims consisted of a high-level application of Hooke’s law — the equation that describes a relationship between mass, stiffness and the frequency at which an object vibrates.

The patent owner argued that the inventors created improved processes for implementing this natural law to create these liners. The court did not agree. While there may have been some patentable refinements to prior techniques in the application, the court found that the claims didn’t include anything other than an open-ended method of liner tuning to achieve a desired result.

Could this case be a concern for medical device manufacturers? Certainly. The Federal Circuit is the sole court hearing patent appeals and the second-highest court in the country (behind the Supreme Court). Whether or not this decision is reversed, medical device manufacturers would be wise to claim the specific aspects that demonstrate the improvements in their invention and not merely recite them in the broader patent specification. Numerous cases examining claims under the Mayo/Alice framework have found that the claimed elements are the most important aspects for patent eligibility, and this case is no outlier in that respect.

One illustrative example of this need to claim a specific method or mechanism — rather than a result —came earlier this year. In CardioNet LLC v. InfoBionic, Inc., the Federal Circuit found a claim drawn to a cardiac monitor patent eligible.

The claims required, among other things, “variability determination logic to determine a variability in the beat-to-beat timing of a collection of beats” and “relevance determination logic to identify a relevance of” that variability. These claim elements provided multiple technological improvements, including improved fibrillation and flutter detection. While the court looked to the specification to confirm that the improvements were, in fact, fully described improvements, the claims were the focus: “We accept those statements [in the specification] as true and consider them important in our determination that the claims are drawn to a technological improvement.”

Cases like these are instructive to medical device manufacturers generally. When drafting a new application, avoid claiming only the result. Instead, claim the thing or steps that give that result. Here are some examples:

An inventor may be able to avoid the patent-eligibility pitfall by claiming the machinery that enables a finer degree of control for her microsurgery system. A medical software developer may find success by claiming the particular algorithm that increases data throughput. A creator of medical-grade thermoplastic may do well to claim the method of creating the material that enables impact, heat and chemical resistance. While these are examples, they demonstrate that medical device companies should take a closer look at their patent claims.

Chris Johns, an associate in Finnegan’s Washington, DC office, works with domestic and international clients on strategic patent counselling, including patent prosecution, drafting strategies, and portfolio management, and speaks and writes regularly on patent topics. He served as a US patent examiner for nearly five years, examining applications related to business methods and software.

Anthony Del Monaco, a partner in Finnegan’s Washington, DC office, focuses on patent litigation, primarily before U.S. district courts and the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC), and arbitrations. Anthony provides strategic guidance to clients on infringement, validity, and enforceability issues, along with post-grant proceedings and licensing negotiations.

Eric Raciti, a partner in Finnegan’s Boston office, has more than 20 years of experience advising companies on intellectual property matters. Eric’s background in IP law includes patent portfolio development, intellectual property enforcement, technology counseling, strategic commercialization strategies, corporate IP policy, technology acquisitions, risk mitigation and due diligence for fund-raising and investment rounds.

The opinions expressed in this blog post are the author’s only and do not necessarily reflect those of Medical Design and Outsourcing or its employees.