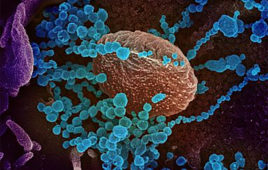

As seen in a dish, Acinetobacter baylyi (green) bacteria surround clumps of colorectal cancer cells. Credit: Josephine Wright/UC San Diego

Scientists at the University of California San Diego, along with colleagues in Australia, engineered bacteria capable of detecting the presence of tumor DNA in a live organism.

Previously, bacteria could perform diagnostic and therapeutic functions, according to the UC San Diego website. However, they lacked the ability to identify specific DNA sequences and mutations outside of cells.

The researchers say this innovation could create a pathway to new biosensors capable of identifying various infections, cancers and diseases. This “Cellular Assay for Targeted CRISPR-discriminated Horizontal gene transfer,” or “CATCH,” demonstrated success in detecting cancer in the colons of mice.

“As we started on this project four years ago, we weren’t even sure if using bacteria as a sensor for mammalian DNA was even possible,” said scientific team leader Jeff Hasty, a professor in the UC San Diego School of Biological Sciences and Jacobs School of Engineering. “The detection of gastrointestinal cancers and precancerous lesions is an attractive clinical opportunity to apply this invention.”

The CATCH method can test free-floating DNA sequences on a genomic level, comparing those samples with predetermined cancer sequences. It engineers cells to detect and discriminate cell-free DNA. The researchers say it could offer value in clinical (cancer and infection) and commercial (ecology and industrial) applications.

“Many bacteria can take up DNA from their environment, a skill known as natural competence,” said Rob Cooper, the study’s co-first author and a scientist at UC San Diego’s Synthetic Biology Institute.

Hasty, Cooper and Australian doctor Dan Worthley collaborated on the idea of natural competence in relation to bacteria and colorectal cancer. They looked into engineering bacteria as new biosensors for deployment inside the gut to detect DNA released from colorectal tumors. The team focused on Acinetobacter baylyi, a bacterium Cooper says features the elements necessary for taking up DNA and using CRISPR to analyze it.

“Knowing that cell-free DNA can be mobilized as a signal or an input, we set out to engineer bacteria that would respond to tumor DNA at the time and place of disease detection,” said Worthley, a gastroenterologist and cancer researcher with the Colonoscopy Clinic in Brisbane, Australia.

The team designed, built and tested the bacterium as a sensor for identifying DNA from KARS, a gene mutated in many cancers. Using CRISPR designed to discriminate mutant from normal KRAS copies, they programmed the bacterium. According to UC San Diego, that meant only bacteria that had taken up mutant forms of KRAS — found in precancerous polyps and cancers — would survive to signal or respond to the disease.

The team based their research on previous methods related to horizontal gene transfer. They say they achieved their goal of applying this concept from mammalian tumors and human cells into bacteria.

“It was incredible when I saw the bacteria that had taken up the tumor DNA under the microscope,” Wright said. “The mice with tumors grew green bacterial colonies that had acquired the ability to grow on antibiotic plates.”

The researchers now aim to adapt the method with new circuits and different types of bacteria, potentially detecting and treating human cancers and infections. They say it requires more development and refinement as the synthetic biology team at UC San Diego works to optimize the strategy.

“There’s a future where nobody need die of colorectal cancer,” said Worthley. “We hope that this work will be useful to bioengineers, scientists and, in the future, clinicians, in pursuit of this goal.”