A physician running Corindus Vascular Robotics CorPath GRX system from the remote control station. [Image courtesy of Corindus]

Although many have experimented with remote “telesurgery,” are the conditions right for commercial companies to start making an investment in a remote robotic surgical future?

Although the idea of telesurgery — performing specialized procedures with robot-assisted surgical tools from a remote location — dates back to the very first research into medical robotics, the technology has yet to make a significant commercial impact.

Robotic surgery is one of the hottest fields in medtech, as a raft of new entrants expand the possibilities for minimally invasive surgery. But thus far, commercialized systems are operated in a same-room cockpit or nearby control room. Is a remote solution viable? Opinions vary, but experts agree on one thing – the hurdles are daunting.

Corindus Vascular Robotics (Waltham, Mass.) is one of the more optimistic players in the field. In January, the company announced a joint project with the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., for pre-clinical testing of its CorPath GRX platform in “telestenting” procedures. Doug Teany, R&D and operations SVP, told Medical Design & Outsourcing that Corindus is optimistic that the tests are a significant step toward a viable telesurgery technology.

“For us, technically speaking, we’re very confident that this can be done,” Teany told us. “We’re so confident that it can be done that we’ve actually already done it in the office through a local area network connection — where we’ve gone further than one room away, but across a building in our headquarters.”

The remote simulation was performed by Dr. Ryan Madder of Spectrum Health in Grand Rapids, Mich., operating CorPath via telecommunication systems with no direct cable connection.

“He was able to complete a procedure, communicating through video and audio with a technician in our demo room,” Teany said. “So we have the technology to do it today; [now] we have to figure out the commercial infrastructure to scale that technology to across buildings and across miles.”

A first-generation version of Corindus’ platform was used in a larger remote experiment as well, Tal Wenderow, Cordindus’ co-founder and international & business development EVP, told MDO.

That study, also led by Madder, explored the use of the CorPath system during percutaneous coronary interventions controlled from a separate room within the same building.

Results from the 20-subject trial, published last year in EuroIntervention, showed an 86.4% rate of procedural success free from conversion to manual operations and a 95% overall procedural success rate.

Others testing the waters

Other players in medical robotics are also testing the telesurgery waters, but haven’t progressed past proving the concept’s basic feasibility.

TransEnterix CEO Todd Pope told us that although his company’s Senhance platform can be remotely operated, the case for further investment hasn’t yet been proven.

“The capability is certainly there. I think the benefits need to be weighed versus the investment. Right now, robotic surgery is still fairly limited in its penetration. Up until now there have been trade-offs that have needed to be made, and we think we addressed a lot of those trade-offs, so our forseeable future is really invested in getting Senhance systems out into ORs, not only throughout the U.S. but around the world. I think remote connectedness is something that stays on our dashboard for future investments as needed,” Pope said.

Titan Medical (Toronto) CEO David McNally told MDO that his company has also experimented with remote capabilities for its Sport robot-assisted surgical platform.

“We have done some early experiments — and this was before my tenure with the company, which began a year ago — with the ability to operate the system from remote locations across the continent of North America,” McNally told us. “We were able to demonstrate to our satisfaction that technically it is possible to operate a workstation that is remote from the patient cart.”

‘Telesurgery is a completely different ballpark.’

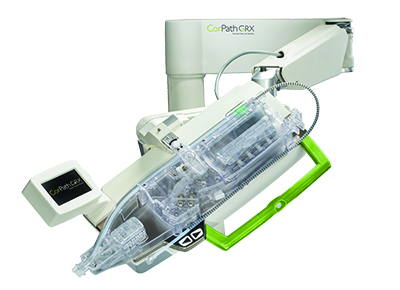

The robotic arm, drive and cassette unit on Corindus Vascular’s CorPath GRX system. [Image courtesy of Corindus]

Creating a commercially viable telesurgery system is much more challenging than creating a non-connected platform, according to Dr. Richard Satava of the University of Washington, a pioneer in medical robotics research with more than 30 years in the field.

Early work with NASA and at Standford University with Dr. Joseph Rosen involved a robotic system for microsurgery on blood vessels a millimeter size or smaller, Satava told MDO. After Satava took a more hands-on role in the project at the Stanford Research Institute, the program shifted its focus to laparoscopic surgery, eventually drawing the eye of the U.S. Defense Dept.’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, he recalled.

“Initially, the director at DARPA wasn’t happy because this project was pretty straightforward and simple and they only do new, innovative things. But I convinced him that no one had actually put together local surgery and remote surgery,” Satava said.

The proposal called for a workstation at a M.A.S.H. unit and a robot-assisted OR at the battle front, “so that when someone would get wounded, immediately the medic would be able to put him in the robotic operating room,” he explained.

The DARPA project progressed as far as two phases, the creation of the remote surgical station and battlefield OR, Satava said. But the funding dried up after the second phase and the program shifted to the Army’s Medical Research Command, he said.

Still, the surgical station technology from the project was later licensed to Intuitive Surgical and used in the da Vinci platform.

“So that’s the basic beginning of robotic surgery,” Satava said. “Telesurgery is a completely different ballpark.”

A number of hurdles would have to be overcome for telesurgery to become a reality, including latency – the lag between the operator initiating an action and the remote system actually doing it.

Another, possibly larger hurdle is coordinating the logistics between the surgeon operating the system remotely and the necessary the surgical site team.

“You have to have a regular surgeon there, at the operating table, in case something goes wrong. You get a specialty surgeon that can do robotic surgery and they could theoretically do it through a smaller hospital in a smaller city, but there still has to be a surgeon right there in case something goes wrong with the robot, so the local surgeon can take over and finish the operation,” Satava said.

Others in the robot-assisted surgery arena echoed Satava’s concerns about telesurgery, including Medrobotics CEO Samuel Straface. Although supportive of the potential societal benefits, Straface wasn’t optimistic about its commercial potential.

“There’s an economy-of-scale issue here, too,” he explained. “To set up a robot remotely requires not only the robot itself, but also requires the expertise of the team to be able to do it.”

And there’s competitions from “verbal assist” procedures, Straface added, in which a surgically trained assistant performs the surgery under guidance from an experienced surgeon at another site. Because the remote procedure would still require at least one additional on-site physician, plus added infrastructure and device costs, remote procedures could prove to be less cost-efficient than verbal assist surgeries – or just flying patients to regional centers of excellence for robot-assisted procedures, he said.

“The law of economics — I think that’s what drives this more than anything else. From a technology standpoint, it can be done, we can do it, we have done it, it’s just, ‘Is there any huge advantage for the patient and operator by doing it?’” Straface said.

“There’s a whole support team required in the sterile field to prepare and assist with loading the specific devices that will be used in the surgery,” Titan Medical’s McNally agreed. “It doesn’t provide the benefit of reducing costs and it may indeed increase the complexity of performing surgery.”

Titan Medical still counts remote connectivity among its goals for the Sport platform, he added, but the focus is on a more realistic short-term goal: The ability to transmit data and images from the surgery to remote locations.

Still, there are successful examples of remote procedures that overcame at least a handful of the hurdles. In one, a team of French surgeons in New York performed a remote surgical operation on a patient in Strasbourg, France, in 2001. Dubbed the “Lindbergh Operation,” it was the first to overcome the time lag inherent in long-distance transmissions.

Dr. Mehran Anvari, of St. Joseph’s Hospital in Hamilton, Ontario, regularly performs procedures using the same platform used in the Lindbergh Operation.

Next steps

Corindus plans to move toward remote operation in phases, setting its sights on “teleproctoring,” in which a single expert is connected to multiple machines to help guide – and if necessary, take over – procedures administrated by less-skilled operators.

“Just like our technology pathway, the development pathway will be very progressive. We will walk our way up to the problem instead of going after a ‘Big Bang’ approach,” Teany told us, adding that an operating prototype is slated for animal studies within the next 30 to 60 days.

The plan is for Spectrum Healthcare’s Madder to operate the CorPath system from a remote site for a procedure performed at Calvin College.

“We’ll have successfully completed a remote animal procedure within the quarter. We have a series of animal labs planned with Mayo this year and next year that will go from that progression of a few rooms away up to metropolitan and wide area networks. And we have a goal as a company to leverage what we’ve learned for a proof of concept, first-in-human PCI done remotely within the next 10 to 14 months.”

The benefits of remote stenting could be huge, Corindus’ Wenderow noted, delivering an enormous boost to the availability of life-saving procedures the world over.

“The city of Beijing has a population north of 23 million. The outpatient population at Beijing’s Buwai hospital is north of 100 million, so people are flocking into Beijing for healthcare, and Buwai has a plan to set up a satellite hospital network for Corindus,” Teany said. “They’re a part of the world that I think is primed for this.”

CorPath might be a better candidate for remote procedures because of the nature of heart attack and ischemia, Wenderow added. Mayo Clinic data shows that even though U.S. PCI capabilities grew 44%, access to the procedure only increased 1%, he said.

“These are not elective procedures. These are procedures we have to treat right now. And when you look at rural health and rural populations, whether it’s in the U.S. or worldwide, the time for the patient to get to the hospital is very long,” Wenderow said, noting that “door-to-balloon” time, the time between admission and catheter balloon treatment, is a key metric.

“The gold standard today is below 90 minutes. Almost all hospitals are doing that. However, we think the problem is not door-to-balloon, it’s ischemia – from the onset of ischemia all the way to treatment with the catheter. That’s a challenge today,” he said.