Our brains have a detailed picture of our hands and fingers, and that persists even decades after an amputation, Oxford University researchers have found. The finding could have implications for the control of next generation prosthetics.

“It has been thought that the hand ‘picture’ in the brain, located in the primary somatosensory cortex, could only be maintained by regular sensory input from the hand,” said team leader Dr. Tamar Makin. “In fact, textbooks teach that the ‘picture’ will be ‘overwritten’ if its primary input stops. If that was the case, people who have undergone hand amputation would show extremely low or no activity related to its original focus in that brain area- in our case, the hand. However, we also know that people experience phantom sensations from amputated body parts, to the extent that someone asked to move a finger can ‘feel’ that movement.

“We wanted to look at the information underlying brain activity in phantom movements, to see how it varied from the brain activity of people moving actual hands and fingers.”

The team, from Oxford’s Hand and Brain Lab, used an ultra-high power (7T) MRI scanner to look at brain activity in two people who had lost their left hand through amputation 25 and 31 years ago but who still experienced vivid phantom sensations, and eleven people who retained both hands and were right handed. Each person was asked to move individual fingers on their left hand.

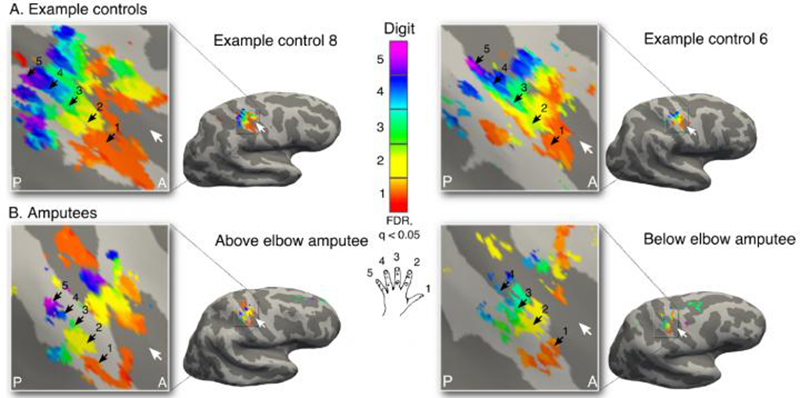

Black arrow indicate preference for digits 1-5: thumb (red); index (yellow); middle (green); ring (blue) and little finger (purple) in two-handed controls (A) and amputees (B). Participants performed single digit flexion and extension movements with their non-dominant (controls) or phantom hand (amputees) in a travelling wave paradigm. Qualitatively similar digit topographies were found in each amputee and controls. White arrows indicate the central sulcus. A = anterior; P = posterior. (Credit: University of Oxford Hand Brain Lab)

“We found that while there was less brain activity related to the left hand in the amputees, the specific patterns making up the composition of the hand picture still matched well to the two-handed people in the control group,” said study leader Ms. Sanne Kikkert. “We confirmed our findings by working with a third amputee, who had also experienced a loss of any communication between the remaining part of their arm and their brain. Even this person had a residual representation of their missing hand’s fingers, 31 years after their amputation.”

One of those involved in the study was Chris Sole. Chris, whose hand was amputated in 1989, has taken part in a number of studies and was chosen for this study specifically because of the strong sense of movement in his amputated hand that he still experiences. He explained: “You feel like you can move your fingers and you have individual control.

“I am always happy to take part in this team’s studies. Especially if it can help other people, the more they can learn the better.”

The current study provides a new opportunity to unlock one of the most mysterious questions about the brain’s ability to adaptively change to new circumstances – what happens to the brain once a key input is lost? To answer this question, scientists so far resorted to studying representations of the remaining (unaffected) inputs to see if these have changed. This approach leaves unexplored the possibility that the original function of the brain may be preserved, though latent. By studying phantom sensations in amputees these findings overturn established thinking in neuroscience by showing the brain maintains activity despite a drastic change in inputs.

Although these findings provide new insight about the brain’s ability to change, they are compatible with other studies of the brain’s visual cortex that found that degenerative eye disease limiting visual input did not change the brain’s representation of the visual field.

Sanne Kikkert said: “It seems that even, as previously thought, the brain does carry out reorganisation when sensory inputs are lost, it does not erase the original function of a brain area.

“This would remove a barrier to neuroprosthetics – prosthetic limbs controlled directly by the brain – the assumption that a person would lose the brain area that could control the prosthetic. If the brain retains a representation of the individual fingers, this could be exploited to provide the fine-grained control needed.”