Metastatic cancer (cancer that spreads to other parts of the body) is responsible for over 90 percent of cancer deaths. Cancer patients’ blood needs to be constantly monitored to ensure that cancer cells from the original tumor don’t break away and migrate across the body. It’s pretty difficult to catch these cells in the act; as a result many of the tests become inefficient.

However, according to a recent study published in Nature Communications, University of Michigan researchers have developed a small implantable sponge that might be able to catch wayward tumor cells, allowing doctors to intercede before the cancer tries to make its home somewhere else.

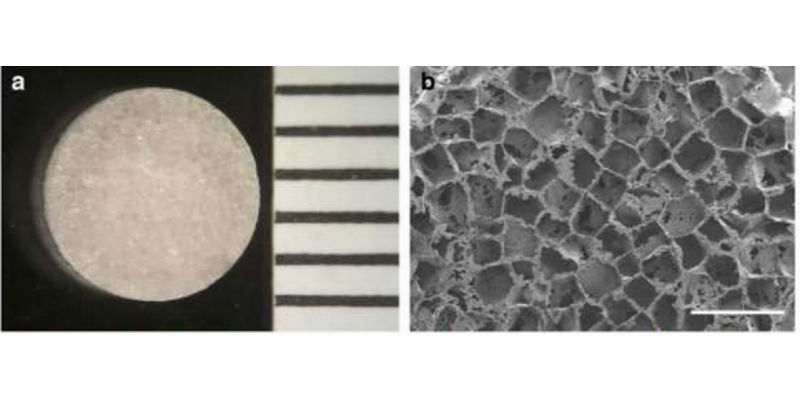

A bunch of the sponges in a petri dish (Credit: University of Michigan Engineering)

They used a plastic called PLGA to make the sponges, a biomaterial already approved for medical device use and dissolves in the body over time. The researchers implanted the 1/5 inch sponges in mice with breast cancer in the abdomen and under the skin – places where cancer doesn’t usually spread. About a month later, cancer cells were found in the sponge, and no cancer cells appeared in those same tissues without it. It was believed that when immune cells rushed to the sponge (as they are wont to do with foreign objects in the body) metastatic cancer cells tagged along, only to meet their demise by becoming trapped in the sponge.

Further, the sponge also caught cells from the original tumor site, reducing the amount of tumor cells by about ten percent. The researchers “tagged” the cancer cells so they would light up, making sure they could be easily identified. According to a BBC article, the researchers plan to use the sponges in human clinical trials fairly soon.

This is a close-up of the sponge (Credit: Nature Communications 2015)

It’s thus far unknown whether metastatic cells will be driven to the implant like they did for the mice, and whether or not the imaging used to spot the cells in mice is safe for human use. However, the team is testing an array of non-invasive scans to monitor the sponge, like ultrasound and optical coherence tomography. Additionally, the sponge would be much larger for humans – and although the PLGA plastic is already used for sutures and dissolves harmlessly, I’m not sure how the body would react to larger lumps of the stuff. (Perhaps those more enlightened of our readers can offer some insight.)

Also, the experiment focused solely on breast cancer, which typically reveals itself with solid tumors. Would the sponge work as well on cancers like leukemia, which doesn’t present solid tumors? Further, will catching metastasis earlier actually improve the patient’s prognosis? The team is working on that – but in the meantime, it’s providing some excellent insight into why cancer cells favor migration to specific areas of the body. If we can understand why cells travel to some places and not others, many therapeutic and diagnostic possibilities become available.