[Image from unsplash.com]

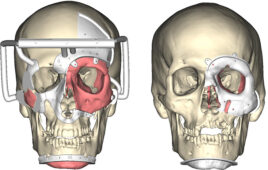

The research team implanted a set of magnets in the eye socket beneath each eye in a patient who has nystagmus. It was one of the first successful uses of oculomotor prosthesis.

“Our study opens a new field of using magnetic implants to optimize the movement of body parts,” said Parashkev Nachev, a member of the UCL Institute of Neurology and the study’s lead author, in a press release.

Nystagmus is an eye condition that results in the eye making uncontrolled and repetitive movements. Because of the movements, people often experience reduced vision and problems with depth perception that can even affect balance and coordination, according to the American Optometric Association. The involuntary eye movements associated with nystagmus can occur from side to side, up and down or in a circular pattern. Approximately 1 in 400 people have nystagmus.

“Nystagmus has numerous causes with different origins in the central nervous system, which poses a challenge for developing a pharmaceutical treatment, so we chose to focus on the eye muscles themselves. But until now, mechanical approaches have been elusive because of the need to stop the involuntary eye movements without preventing the natural, intentional movements of shifting gaze,” said Nachev.

The patient who went through the procedure developed nystagmus in his late 40s from Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The research team developed a prosthesis for him using one magnet that was implanted in the bone at the bottom of the eye socket. The magnet interacted with a smaller magnet that was sutured to an extraocular muscle that controls eye movement. The magnets are enclosed in titanium that allows them to be safely implanted while creating a magnetic force that doesn’t cause any damage.

“Fortunately, the force used for voluntary eye movement is greater than the force causing the flickering movements, so we only needed quite small magnets, minimizing the risk of immobilizing the eye,” said Quentin Pankhurst, lead designer of the prosthesis.

To test the prosthesis before implanting it into the patient, the research team attached the magnet to a custom-made contact lens. Once it was proven to be safe and successful, the patient received the magnetic prosthesis in two separate sessions.

The patient recovered quickly and reported having his vision acuity being substantially improved. There was also no negative impact on the functional range of movement. The symptoms of involuntary eye movement have stayed stable over a 4-year period of check ups.

“While the exact neural mechanisms causing nystagmus are still not fully understood, we have shown that it can still be corrected with a prosthesis, without needing to address the neural cause. What matters here is the movement of the eye, not how it is generated,” said Christopher Kennard, one of the leaders on the study.

The researchers suggest that the magnetic prosthesis is not suitable for everyone. Those who need regular MRIs wouldn’t be able to use the implants and more research needs to be done to determine who would benefit the most from the prosthesis. The researchers are currently working to conduct a larger scale study.

Oxford has recently had a few other vision impairment breakthroughs, including a retinal surgical robot and synthetic retina advances.

The study was published in the journal Opthalmology and was funded by the National Institute for Health Research’s (NIHR) National Program for New and Merging Applications of Technology, NIHR Biomedical Research Centers at UCLH, Moorfields Eye Hospital and Oxford and Wellcome.

[Want to stay more on top of MDO content? Subscribe to our weekly e-newsletter.]