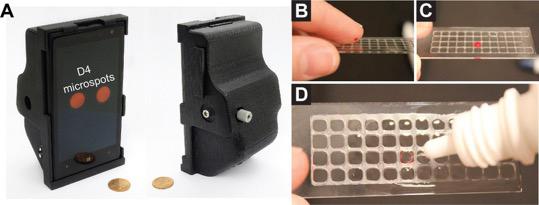

The photo on the left shows the 3-D printed smartphone attachment that uses the phone’s camera to review the results of the assay. The photo series on the right shows the process to administer a blood sample onto the D4 assay. (Credit: Daniel Joh, Duke University)

Biomedical engineers at Duke University have created a portable diagnostic tool that can detect telltale markers of disease as accurately as the most sensitive tests on the market, while cutting the wait time for results from hours or even days to 15 minutes.

Created by inkjet-printing an array of antibodies onto a glass slide with a nonstick polymer coating, the diagnostic tool, called the D4 assay, is a self-contained test that can detect low levels of antigens, the protein markers of a disease, from a single drop of blood. By creating a sensitive, easy-to-use “lab on a chip,” the researchers plan to bring rapid diagnostic testing to areas that lack access to standard lab-based diagnostic technologies.

The platform is described August 7, 2017 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Beyond detecting diseases, healthcare workers use diagnostic tools to assess the severity of an illness, plan an effective treatment strategy, and track an individual’s response to treatment. While some tests, like the lateral flow test, are fast, portable and easy to use, they aren’t usually sensitive enough to provide information beyond the presence or absence of a particular biomarker, so healthcare workers often need to use quantitative methods to determine how severe an infection is.

Currently, the gold standard for quantitative diagnostic tests is the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), which identifies how many specific antigens are present in a biological sample. While ELISA is among the most sensitive immunoassay tools on the market for detecting diseases like Zika and HIV or tracking hormone levels in the blood, it requires trained researchers or liquid handling robotic devices to follow a series of time-consuming steps to ensure that no unwanted proteins stick to the assay and muddy the results. The test also requires bulky laboratory instruments for data analysis, making it ill-equipped for use in resource-limited settings.

As an added complication, the ELISA platform can take up to 24 hours to show test results –which often means a delay in treatment even as the disease continues to spread.

The D4 assay allows clinicians to avoid these problems without sacrificing sensitivity or accuracy. The new assay can identify a disease biomarker in as few as 15 minutes, and results can be read using a tabletop scanner or 3-D printed smartphone attachment that uses the phone’s camera to read the results, enabling the tool to be used in point-of-care settings for rapid diagnosis.

Like the ELISA platform, the D4 assay uses a matched pair of antibodies to detect and capture a target protein in a blood sample. The array contains two types of antibodies –immobilized capture antibodies and soluble detection antibodies –which are tagged with a fluorescent marker to allow the researchers to identify how much of the antigen is present. When a drop of blood is placed on the slide, the detection antibodies dissolve, separate from the array and bind to the target proteins in the blood. These fluorescing antibody-protein pairs then attach to the capture antibodies that are still on the slide.

But unlike other diagnostic tests like the ELISA or lateral flow test, D4 assay’s antibody array is printed on a novel polymer brush coating. When a sample is placed on the slide, the coating works like Teflon to prevent the non-target proteins from attaching to the surface of the slide. By preventing unwanted proteins from binding to the assay, the polymer brush makes it easier to detect low levels of target proteins by getting rid of the ‘background noise’ on the chip.

“The real significance of the assay is the polymer brush coating,” says Ashutosh Chilkoti, chair of the Department of Biomedical Engineering (BME) at Duke and senior author on the paper. “The polymer brush allowed us to store all of the tools we need on the chip while maintaining a simple design.”

Using the D4 assay, researchers don’t need to follow a complicated workflow to clear non-target proteins from their slide, as with the ELISA test. Instead, they simply need to wash the slide in a buffer solution to remove any extraneous particles.

As a proof-of-concept for the accuracy of their assay, the research team conducted a clinical trial to measure the serum leptin levels in patients at Duke University Medical Center and compare them to those observed with the clinical ELISA platform. A previous study from Michael Freemark, a professor of pediatrics at Duke University School of Medicine and a senior author on the paper, showed that low serum leptin levels could predict mortality and complications in severely malnourished children. Leptin levels are typically measured using ELISA, but the researchers recognized that if they could use the D4 assay to accurately test for leptin levels, the tool could be used to plan better treatment for those suffering from malnutrition in resource-limited settings. The study found that the results from the D4 assay were on par with those from the ELISA test.

“What’s cool is that our assay can achieve comparable sensitivity to the ELISA within 15 minutes, and if further sensitivity is needed, longer incubation times can be used,” says Daniel Joh, an MD-PhD student in the Chilkoti lab and co-author of the paper. “This device can also be compared to a lateral flow test, which is quite fast as it takes less than five minutes to get a reading, but that test isn’t as sensitive. This is really the best of both worlds.”

Unlike the ELISA, the D4 assay is a highly portable tool, as the dry slides don’t need to be refrigerated during transport. The design is also cost-efficient–Joh and his collaborators estimate that the D4 chips will cost less than one dollar and the mobile phone attachment developed at the University of California, Los Angeles will be less than $30 when they are produced in bulk.

Next, Joh and Angus Hucknall, co-author of the paper and a senior researcher in the Chilkoti lab who previously developed the polymer brush technology with Chilkoti, will also conduct a field test of the prototype tool in Liberia, screening participants’ serum leptin levels to gain a better understanding of how diagnostic results from the D4 assay can be used to monitor and plan treatment strategies for malnutrition. The team also plans to study how they can use the tool to perform a wider array of diagnostics.

“The D4 assay enables us to conduct high-performance diagnostic testing with minimal resources, making it a promising platform for increasing access to sensitive and quantitative diagnostic tools,” says Hucknall.