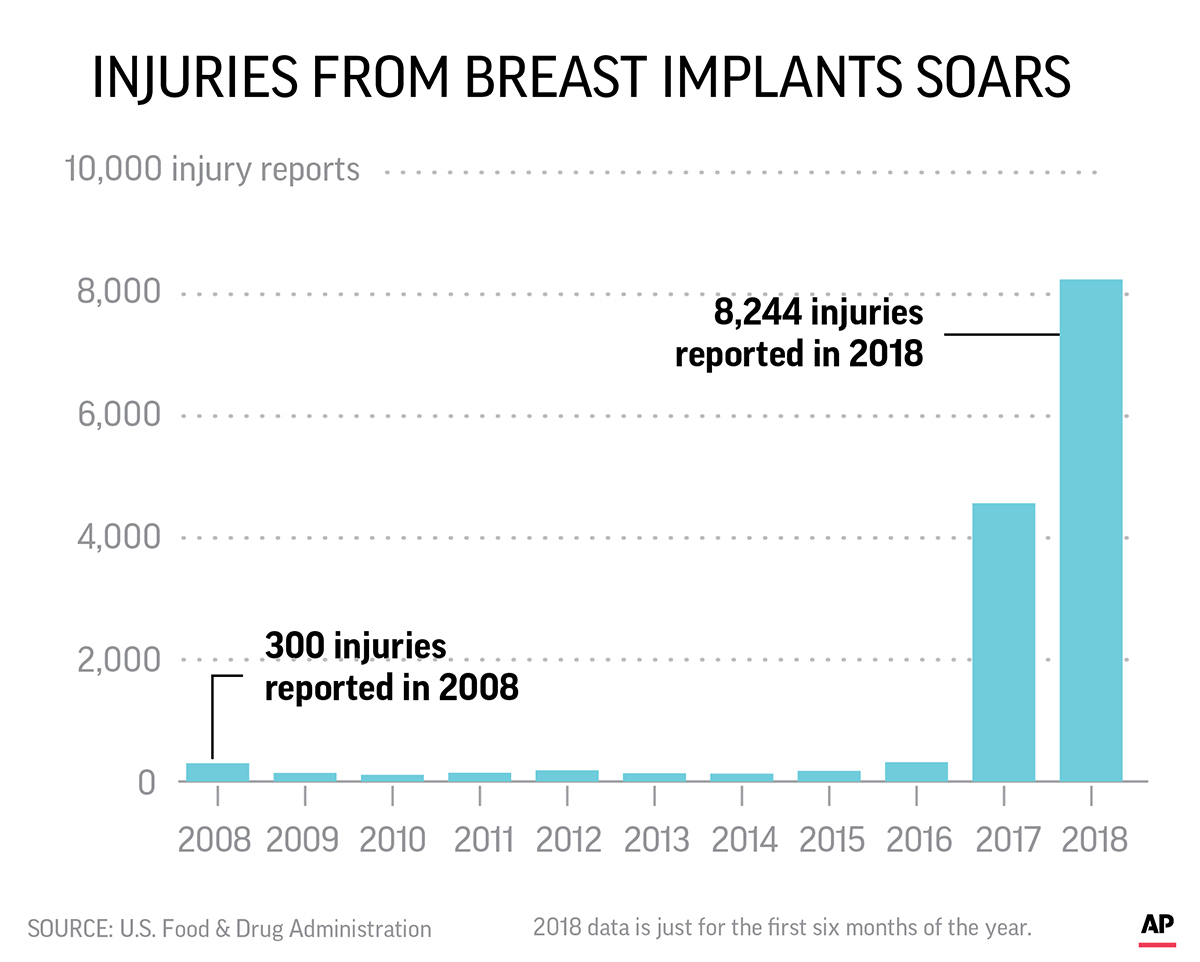

To all the world, it looked like breast implants were safe. From 2008 to 2015, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration publicly reported 200 or so complaints annually — a tiny fraction of the hundreds of thousands of implant surgeries performed each year.

Then last fall thousands of problems with breast implants flooded the FDA’s system. More than 4,000 injury reports filed in the last half of 2017. Another 8,000 in the first six months of 2018.

Suddenly, women like Jamee Cook had evidence suggesting their suffering might be linked to their breast implants. An emergency room paramedic, Cook had quit her job because of a vague but persistent array of health problems that stretched over a decade, including exhaustion, migraines, trouble focusing and an autoimmune disorder diagnosis.

Why had it taken so long for complaints like hers to see the light of day?

Breast implant companies were required to track patients and their health. But for more than a decade, manufacturers with high numbers of recurring problems — in the case of implants, ruptures that required surgery to remove — were allowed to report issues in bulk, with one report standing in for thousands of individual cases and no way for the public to discern the true volume of incidents.

That agreement stood even as the FDA began closely monitoring a rare type of cancer and acknowledged in 2011 that it might be linked to breast implants.

“It looked like these devices had become safer, but they hadn’t,” Cook told The Associated Press. “The data was hidden. It’s a deceptive practice.”

Jamee Cook poses for a photo at Rayburn House Office Building after meeting with congressional leaders on Capitol Hill, Thursday, Sept. 6, 2018, in Washington. Cook had breast implants that ruptured and which she believes caused her medical problems. She now is lobbying the FDA and congressional leaders to do a better job of tracking and regulating medical devices. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana)

Once Cook’s textured saline implants were removed, she said the majority of her symptoms disappeared. Her experiences prompted her to become a patient safety advocate, lobbying lawmakers and organizing groups of women online who have concerns about breast implants.

But even as the FDA was dealing with breast implant reporting problems, the agency was moving to expand flexibility in reporting medical device issues.

This August, the agency began allowing roughly 90 percent of all medical devices — including breast implants and more than 160 types of other high-risk implanted devices — to report malfunctions quarterly. Manufacturers will not be able to report cases involving deaths or injuries that way, however.

The FDA rejected claims that it would make problems with devices less transparent, saying it would help speed the processing of malfunction reports and analyzing trends.

Two of the largest manufacturers, Mentor and Allergan, said they stood behind the safety of their products. In response to patients like Cook, who have voiced concerns that autoimmune disorders occur more frequently in implant patients, the companies cited years of studies that have led to no or inconclusive evidence that the disorders are linked to breast implants.

Still, it can be hard for breast implant patients and advocates to track problems that do arise.

Insurance claims make no mention of the specific device or model implanted in a patient, and patients’ electronic health records aren’t required to record that either. Products sold overseas can be renamed or carry a different model number, making tracking across borders nearly impossible.

Meanwhile, the FDA’s main database on medical device problems, which requires manufacturers to report patient deaths and serious injuries to the government within 30 days, relies on hand-typed entries to help track troubled products. That can lead to underreporting, along with missing and flawed data.

Madris Tomes, a former FDA analyst who now runs a company that analyzes medical device data for private businesses, said she believes the FDA data represents the lowest possible count of problems. “You can assume that the numbers are probably much, much higher,” she said.

S. Lori Brown, a retired FDA senior researcher who used the agency’s database for years in her studies of breast implants, said the data showed silicone implants leaking gel into thousands of women’s bodies in the 1990s.

“As a signal, it was a burning bush, for sure,” Brown said. “Because there were so many reports of ruptured implants from every manufacturer.”

The FDA removed silicone implants from the market in 1992, but they returned in 2006 with the requirement that companies track patients for at least a decade.

A change in FDA reporting policies in 2017 meant that reports of injuries from silicone gel-filled and saline-filled breast implants skyrocketed in the past year. Injury reports used to be provided in a quarterly tally, with one report standing in for thousands of individual cases.

Although more than half the women dropped out of the studies within the first two years, researchers at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston used the data in a study released this September that found that certain rare health problems — including immune system and connective tissue disorders — might be more common with silicone gel implants. The FDA, which mandated the original data collection, later criticized the study, citing “inconsistencies in the data.”

Last year, however, the FDA did confirm a link between breast implants, particularly textured saline or silicone models, and anaplastic large cell lymphoma — a rare cancer documented in only a few hundred cases.

On its website, the FDA warns that implants “are not lifetime devices,” but will likely need to be removed or replaced at some point.

The return of silicone fueled a surge in surgeries. The American Society of Plastic Surgeons reported more than 400,000 implant procedures took place in 2017, up almost 40 percent compared to 2000.

In September, Cook and 19 other breast implant patients-turned-health-advocates visited Washington to lobby the FDA. Among their requests — that all types of textured implants be banned from the market, and that manufacturers be required to disclose the chemicals in silicone implants’ shell and gel filling, which the makers claim is a trade secret.

The FDA, which says the uptick in medical device reports about breast implants “does not . indicate a new public health issue,” has scheduled an advisory committee hearing for early 2019 on implant safety to address some of the U.S. group’s concerns.