At first, Vincent Karst, 55, was recovering well from his open-heart surgery in March 2015.

He resumed the activities he enjoyed, such as visiting car shows and eating out. But some months later, his condition mysteriously deteriorated. By fall he was so short of breath, nauseated, and overwhelmed by fatigue that he needed to be rehospitalized in York, Pennsylvania.

There, doctors diagnosed a new problem: a serious mycobacterial infection that was acquired during his surgery, according to his subsequent lawsuit. Aggressive treatment with antibiotics left him with partial hearing and vision loss.

Federal regulators acknowledge they were aware of infections tied to a heart-surgery device used in Karst’s operation by the summer of 2014. But they waited 14 months before issuing a public alert about the risks, and it wasn’t until last month — more than two years later — that they issued detailed recommendations to hospitals and patients on what to do.

Critics say a swifter response could have saved thousands of patients like Karst from being exposed to potentially deadly bacteria. Some patients fell ill or died without knowing the real cause, doctors say.

Now hospitals, which consider the heater-cooler machines crucial in open-heart surgery, are scrambling for ways to protect patients. And authorities have urged hospitals from New Jersey to California to notify hundreds of people who underwent surgery in recent years that they might be harboring a dangerous infection. Patients have sued, claiming they were infected in Pennsylvania, Iowa, South Carolina, and Quebec.

(Image credit: AP Photo/Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Bob Riha, Jr.)

Experts and patient advocates say these cases are only the latest to expose holes in the nation’s approach to spotting and responding to dangerous deficiencies in medical devices.

“It’s another example of the poor oversight of medical devices and how the industry has accepted infection as the cost of doing business,” says Helen Haskell, founder of the patient advocacy group Mothers Against Medical Error in Columbia, South Carolina

About 60 percent of U.S. hospitals that do heart surgeries rely on the Sorin 3T heater-cooler device used in Karst’s surgery, which was approved for sale in 2006. But five other manufacturers sell heater-coolers in the U.S., and FDA officials say they share similar design features that make them prone to contamination.

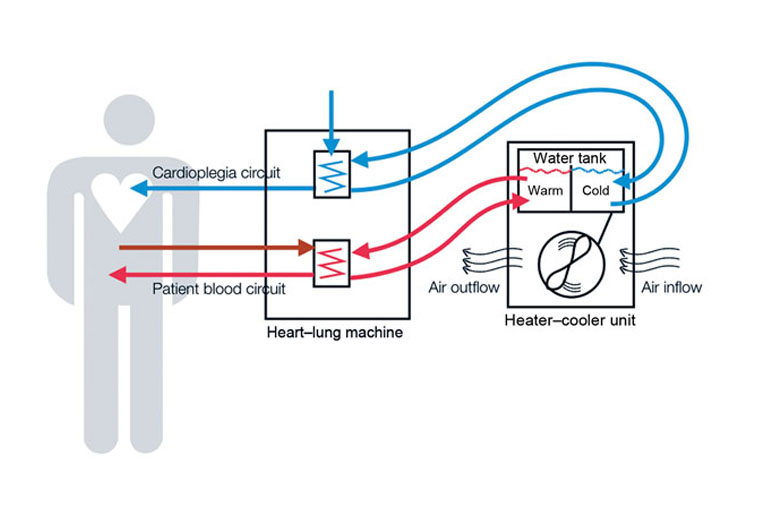

The devices circulate water to warm or cool patients during bypass surgery, valve replacements, and some transplants. More than 250,000 heart bypass operations using heater-cooler devices are performed annually in the U.S. The infections caused by the devices can be slow-growing and often don’t trigger symptoms for months or even years, making them difficult to track.

Schematic representation of heater–cooler circuits tested for transmission of Mycobacterium chimaera during cardiac surgery despite an ultraclean air ventilation system. Blue arrows indicate cold water flow, and red arrows indicate hot water flow and patient blood flow. (Courtesy of CDC)

As a result, the risk is hard to quantify. At least 79 cases of infection tied to Sorin heater-cooler units in the U.S. and worldwide have been reported to the FDA since 2010, including 12 deaths. Those numbers are expected to rise.

“This particular machine is everywhere and it will be quite a while until we know the real extent of how many people were infected by this,” says Dr. Michael Edmond, an epidemiologist at the University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics.

The potential for contamination of heater-coolers was raised as early as 2002. In a published study, doctors at a German hospital found that “germs and particles pollute” the units and that disinfecting them is very difficult.

The study, presented at a medical conference in New Orleans, said the makers of the devices often “do not provide any technology to reduce bacterial or other contamination,” posing potentially serious consequences for patients.

The study focused primarily on water spilling out of the unit and contaminating the operating room. But it also raised the prospect of waterborne pathogens causing infection through “aerosolization” — which is believed to be the way the recent infections occurred. The units examined were not Sorin devices.

The FDA visited Sorin’s Munchen, Germany plant in April 2011 to address safety concerns about the heater-cooler machine, according to a lawsuit filed this month. That suit says Sorin’s instructions for disinfecting the heater-cooler every two weeks allowed for “bacterial overgrowth well in excess of safe standards” in just a day and a half.

Despite the 2002 German study, a spokeswoman for Sorin, Karen King, says the company wasn’t aware of the threat of airborne mycobacteria until receiving a report from Swiss authorities in January 2014. (Sorin merged with another company last year to form London-based LivaNova.)

The water in the devices doesn’t come in direct contact with patients so there wasn’t much concern about infection until recently, health officials say. But it turns out lethal bacteria can grow inside the machine and then become aerosolized through the unit’s exhaust fan. The germs can float down into the patient’s open chest or stick to an implantable heart valve.

King said the initial details concerning bacteria transmission were limited and Sorin began investigating in 2014. The results led the company to notify hospitals in July 2014 that some of its heater-coolers had become contaminated and there was a risk of mycobacteria infecting cardiac patients.

Still, the company has maintained to the FDA that “post-surgical infection appears to be exceedingly uncommon.”

“We are working with regulators to develop a solution that addresses their concerns and ensures continued clinician access to this important device which enables lifesaving cardiac surgery,” LivaNova says in a statement. The company declined to answer additional questions.

LivaNova posted $1.2 billion in sales for all of its devices last year and says that half of the world’s cardiac surgeries rely, at least in part, on its equipment.

The FDA said it too was caught off guard by the danger posed by heater-coolers and has defended its handling of the matter.

“This is an evolving story in terms of new information that became available as a result of ongoing studies and efforts in the U.S. as well as outside the U.S.,” says Suzanne Schwartz, an associate director at the FDA’s center for regulating medical devices. “It might seem to have taken a fair amount of time, but one of the challenges has been raising awareness in the health care community that this is a problem that needs to be addressed.”

An FDA spokeswoman, Angela Stark, says the agency received at least two reports of infection tied to heater-coolers in 2009 and 2010. Details of those reports weren’t available in the FDA’s public database of injury reports.

The agency didn’t begin investigating until mid-2014. That was when it learned of the alert Sorin sent to hospitals and also around the time of an unusual infection outbreak at a South Carolina hospital, Schwartz says. The FDA says it only learned in spring 2015 that heater-coolers could blow bacteria across the operating room.

“It came as a surprise to the health care community at large,” Schwartz says. “Once that recognition was there, we have been working very proactively with all the device manufacturers.”

Many — but not all — of the confirmed infections involved an organism called Mycobacterium chimaera, a species commonly found in soil and tap water. They aren’t generally harmful to healthy people, but officials said they can lead to serious infections in patients who are already ill or have weakened immune systems.

The source of the contamination from heater-coolers can be two-fold — at the manufacturing plant and in hospitals themselves.

Last month, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced that an analysis of patient samples had confirmed that contaminated Sorin machines had been shipped through the summer of 2014 from the company’s German factory.

The company told the FDA it addressed the contamination by introducing sterile water at the plant and adopting new disinfection measures in August 2014.

Still, the heater-cooler machines can also become contaminated from the local water hospitals pour into the units. And however the contamination occurs, the FDA has said the bacteria can be difficult to remove even when the manufacturer’s cleaning instructions are followed.

Some medical experts say the South Carolina outbreak in 2014, at Greenville Memorial Hospital, should have triggered a more forceful response by U.S. health officials, including the FDA.

That year, when investigating mysterious infections among more than a dozen patients, the CDC found a form of mycobacteria different from the one in the German plant in an operating room sink and in the Sorin heater-cooler being used.

Dr. Michael Bell, a CDC deputy director, said the outbreak was complicated because some of the infected patients had no link to the heater-cooler during their treatment. Nonetheless, he said the heater-cooler contamination could have contributed to some of the patient infections. Four patients infected with the mycobacterium died.

Lawrence Muscarella, a hospital-safety consultant in Montgomeryville, Pennsylvania, said federal officials should have sounded the alarm over mycobacteria and heater-coolers after the 2014 Greenville hospital outbreak. “Some deaths might have been avoided if the FDA and CDC had performed a more proactive investigation.”

According to a lawsuit filed this month, a patient treated in a North Carolina hospital alleged that he was infected during a June 2015 liver transplant after a heater-cooler machine exposed him to the same bacteria implicated in South Carolina.

Some patients and their families are left wondering why the device maker and government officials didn’t notify the public sooner. “Why wasn’t more being done?” said Jaime Jackson, an attorney representing Karst, the York patient.

WellSpan York Hospital and LivaNova both declined to comment on Karst’s lawsuit, citing the pending litigation. Overall, the Pennsylvania hospital has reported 12 infections tied to the heater-coolers, and six of those patients have died. It has notified roughly 1,300 patients about possible exposure dating to 2011, according to WellSpan.

Meanwhile, the FDA has said heater-coolers “remain critical to patient care” and can’t be removed without a viable alternative.

That has put many hospitals in a quandary. Some hospitals, such as the University of Iowa, chose to cut holes in the operating room walls, moving the units next door so the fan exhaust isn’t falling on patients and surgical instruments. “If I was having cardiac surgery, I would want that machine out of the room,” says Edmond, the University of Iowa doctor.

But the CDC said that approach isn’t always feasible. Other hospitals have put enclosures around the machines or pointed the exhaust fan away from patients and the surgical field. Many are now using sterile or filtered water in their machines, as health officials have recommended.

“I don’t think we have a one-size-fits-all solution for this,” the CDC’s Bell says. “The reality is this is a wakeup call for the design of many medical devices, especially those in critical places like the operating room.”

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation. This story also ran in The Daily Beast.